Patsy Lam honors ‘one-of-a-kind’ Mary Luo *85 with new graduate fellowship

Mary Luo, October 2023 (Photo by Carrie Rosema)

The home on Hartley Avenue in Princeton is warm and elegant. Patsy Lam has lived there for nearly 60 years, and it is full of natural light and positive energy. She welcomes her guest with a smile and invites him to sit down across from her, near a tray of refreshments on the coffee table. Everything in the room feels precise and purposeful.

Her late husband, Professor Harvey Lam *58, designed the house himself, and together they raised three children in it while thriving in the University’s academic community in part because of their remarkable hospitality. Professor Lam, who passed away in 2018, taught at Princeton for 40 years and retired in 1999 as the Edwin S. Wilsey Professor Emeritus of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering. Patsy Lam was a longtime volunteer for what is now known as the Kathryn W. and Shelby Cullom Davis ’30 International Center.

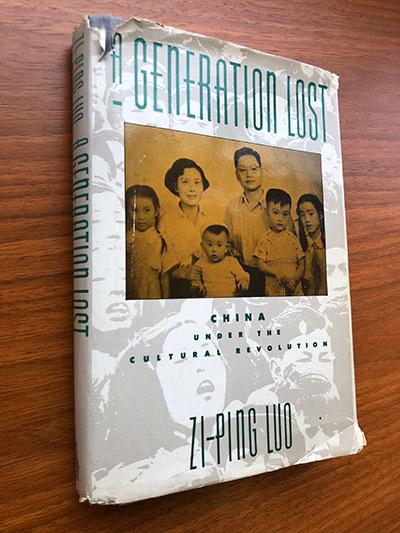

When Patsy and Harvey were teenagers, their families fled Shanghai before the end of the Chinese Revolution of 1949 when mainland China was taken over by the Communist party. Harvey was one of the few Chinese students at Princeton in the mid-1950s, when he studied aeronautical engineering. The couple met in New York and married in 1959, the same year Harvey started his first job as an assistant professor at Cornell. The Lams have lived an amazing story, but it’s not the one Patsy wants to tell today. She points to a book that she has carefully placed on the coffee table. On the book’s cover is a sepia-tinted photo of a Chinese family. “All I want to do is to share Mary’s story,” she said. “She is really one of a kind.”

Mary is Mary Luo *85, who arrived at Princeton in 1980 as part of the first cohort of Chinese students following the thawing of relations between China and the West. Of the 265 Chinese students — including many research fellows and assistant professors — who took the exams for the Chinese Academy of Science that would open the door to graduate study, Luo was one of only nine who passed. She was the youngest of the nine and the only woman, but that’s not all that made her stand out: she had never finished high school.

Luo came from a family of Shanghai intellectuals. Her mother was a journalist and her father was an encyclopedia editor before the Cultural Revolution, but when Luo was in the ninth grade, her family was labeled as anti-revolutionary. Her mother was imprisoned for 14 years, her father was confined under house arrest, and Luo was assigned to work as a lathe operator. The schools and universities were closed, and books were forbidden.

Luo and her siblings vowed to educate themselves in secret, with the help of friends who risked their own safety to smuggle books to them. “We would copy the books by hand, and I would systematically study them by dim light at night,” Luo said. “Sometimes we didn’t know what we were studying, but I made up my mind to study chemistry, physics, mathematics and all the subjects that I couldn’t finish in high school. Then later, I started to teach calculus and quantum chemistry to myself.”

After she passed the test, she attended the University of Science and Technology near Shanghai, but her family was never fully reunited. Her father died of lung cancer in 1979 and her mother died shortly thereafter from a stroke. Two of her uncles who came from Taiwan taught in the United States, and one suggested that she apply to an Ivy League school because these schools might be more inclined than a state university to make an exception and admit a student who lacked a conventional academic record. That advice proved correct, and Luo was accepted by Princeton and Yale, as well as Johns Hopkins and Stanford. She selected Princeton because she associated the University with Albert Einstein. She arrived at Princeton with just $25 and a suitcase full of her treasured books.

At Princeton, Luo was understandably homesick. She had recently lost her parents, wasn’t as polished as her academic peers and she didn’t understand English well. She learned that the International Center paired new students with host families, so she inquired. “I met Mrs. Lam there,” Luo said. “Her smile was infectious, and I felt eager to talk to her about everything: my homesickness, my loneliness, everything. She was very helpful.”

“Harvey and Patsy took a special interest in helping the new Chinese students learn American ways and feel at home in what must have been a very strange land for the students,” said Professor Herschel Rabitz, Luo’s advisor and the Charles Phelps Smyth ’16 *17 Professor of Chemistry.

A few months later, Patsy Lam invited Luo to dinner at their home. During the meal, Professor Lam, who was renowned for helping Princeton students from all different disciplines, conveyed an invitation from Rabitz for Luo to join his chemistry research group. “I was very touched because I didn’t realize that there were people who cared about my feelings and happiness,” Luo said. “From that day on, I fell in love with the Lams. They both came from Shanghai, too, so we could speak the same dialect. We had a lot of common foods we liked, and I really didn’t feel any nervousness in front of them. Meeting the Lams was a very important event in my life.”

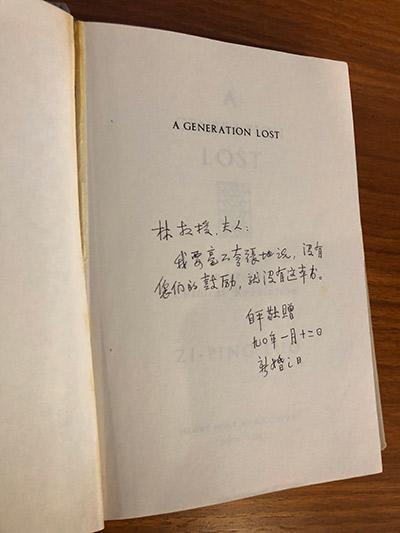

Over the next few years, Luo found her stride at Princeton. She also began to reflect on her own story. During the Cultural Revolution, Luo not only consumed math and science books; she also devoured literature and novels. In her spare time as a graduate student, she began to write her memoir. “I did not know whether it was a good idea so I consulted Professor and Mrs. Lam,” Luo said. “I remember Professor Lam said, ‘Writing this book possibly will be the most important project you will do.’ So I was very much encouraged, and I sent him the chapters I’d already written for him to read.”

Those chapters became “A Generation Lost,” which eventually was published in 1990. “Luo writes vividly and her story, with its many excerpts of poetry, often reminds one of a traditional tale of a Chinese heroine — modest, virtuous, generous to a fault, dutiful, brave and persevering,” wrote a reviewer in the Washington Post. “Her life as it stands is an inspiration in itself.”

After Princeton, Luo went to California Institute of Technology as a post-doctoral research associate. In 1989, she joined the faculty of California State Polytechnic University, where she taught chemistry for 17 years. “I always told my students that if I could teach myself during the pressure of the Cultural Revolution, there is no reason they cannot pass their exams,” she said.

In 1990, she married Jack Zhang, a fellow chemistry postdoc she had met at Cal Tech. “Jack was one of the nine Chinese students who passed the same test as Mary to attend graduate school,” Lam said. “That’s yuánfèn — like destiny — that the world is so big and two people who cross paths can meet again at a certain place and even get married.”

By training, Luo and Zhang were “dry” chemists who specialized in theoretical chemistry and pure mathematics, respectively, but they began to think they could make a greater impact by shifting their focus to environmental protection. They established Applied Physics and Chemistry Laboratories (APCL), a wet lab working with the EPA to test and clean up military bases that were transitioning to civilian use after the Cold War. They didn’t have a precise background in this field, but they learned quickly and became confident they could do the job better than others. “The military needed to make sure that all the storage tanks that contained some explosives or other materials that leaked into the soil were cleaned up, so we chemists became the eyes of the engineers,” Luo said.

They needed some help at the beginning to get APCL up and running. “When I shared this idea with Mrs. Lam, she was very supportive,” Luo said. “Then she suggested she could support us from her own savings.”

“They were working so hard, day and night, to start that lab,” Lam said. “I let her use a very small sum so they could get started.”

With that financial boost, the lab quickly proved its worth. “The program of the Army Corps of Engineers required all applicants to pass a very difficult test to make sure the qualified laboratories had excellent analytical skills, and we scored 100% on our first attempt, breaking a record that goes back 130 years,” Luo said. “So we became quite popular.”

The success of APCL gave Luo and Zhang the confidence to think even bigger, and they became interested in pharmaceuticals. “Jack and I felt that the United States had given us such a great opportunity and that we could do more,” Luo said. “We decided to learn about mass production and automation in such a way that every batch, every bottle of a drug exactly followed the same good quality standard. It is a challenge to apply good manufacturing practice in the pharmaceutical industry. To this day, we are constantly learning.”

The couple co-founded Amphastar in 1996, and the company now has five manufacturing facilities on three continents where they develop and produce injectables and inhalation products. Luo is Amphastar’s chief operating officer, chief scientist and chairman of the board. Zhang is the company’s chief executive officer, president, chief scientific officer and director.

Rabitz marveled at the path of his protégé’s career. “Over her full graduate career, Mary remained a very quiet individual, but she knew exactly what she wanted to do in life,” he said. “When she left Princeton, she told me that she was going to do the following: get married, have a family, publish a book about the Cultural Revolution, become an academic and start a company. Indeed, she did all of those things. She and her husband climbed the business ladder with hard work. It is the American Dream!”

Not long ago, when Lam was doing some organizing at home, she rediscovered the original manuscript of Luo’s memoir, written in Chinese. This reminded Lam of the quiet young woman who worked so hard for so many years to overcome enormous challenges.

Princeton has been an enormous part of Lam’s life. “I have three children born here, my daughter was a Class of ’84, one grandson was a graduate in 2019 and another is a junior now,” Lam said. “I almost had a free Princeton degree myself because I audited so many classes as a faculty wife. I got a lot out of Princeton.”

The Lams have given back to Princeton, too. They supported the University through gifts to establish the Patsy and Harvey Lam *58 Family Scholarship Fund and the Harvey S.H. Lam *58 Endowed Fund in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering. Earlier this year, Lam spoke to her children about making a new gift to Princeton that would provide a new graduate fellowship. They agreed to name it the Mary Zi-ping Luo *85 Graduate Fellowship.

“For me, I want to have Mary remembered by giving this small thing to Princeton so that her name can go on,” Lam said. “She has gone through so many hardships and taken enormous risks, but she is so strong. If somebody else can benefit from this fellowship, it would be nice.”

When Luo was informed of Lam’s gesture, she was extremely touched. “My success today is all because of your unfailing encouragement and support,” she wrote to Lam. “I will work even harder to deserve you, Professor Lam, and the name of Princeton.”