Photo by Matthew Raspanti, Office of Communications

In their teaching and research, Princeton University’s humanities faculty keep their intellectual antennas tuned to what Dean of the Faculty Gene Jarrett calls “the frequencies of ideas,” crackling with the collected genius of human culture from across the globe and across time.

Classics professor Barbara Graziosi’s frequency spans millennia.

Graziosi is developing AI-based tools to fill in the gaps of fragmented ancient texts that are written on stone, papyrus and parchment so those valuable voices from the past are not lost forever. “The ancient world was as big as the modern world, and there were many different languages, traditions and ideas that are worthy of attention,” Graziosi said.

The endgame for her natural language project “is to make the whole diversity of human expression available to our curiosity, for inspiration for the future,” she said.

Graziosi’s project is exemplary of Princeton’s overall approach to studying and teaching the humanities, in which scholarship tackles universal questions and helps society navigate the future of our rapidly changing world. “The humanities imbue us with a deeper understanding of what it means to be human,” said Jarrett, the William S. Tod Professor of English and a Class of 1997 Princeton graduate.

The University is embarking on a sweeping new commitment to humanities scholarship to expand its impact on campus, in higher education and in the wider world. A new Princeton Humanities Initiative will bring faculty together from across disciplines to collaborate on shared intellectual projects.

Director Rachael DeLue said the new Humanities Initiative will strengthen interdisciplinary connections and intellectual community across the humanities and beyond. The goal is to supercharge the University’s capacity “to take really big swings at big ideas,” she said.

Supercharging an interdisciplinary powerhouse

The humanities at Princeton encompass more than 50 academic departments and programs, spanning art and archaeology, classics, philosophy, languages, music, aspects of history and other social sciences, and creative programs housed in the Lewis Center for the Arts. An emphasis on interdisciplinary connections within and beyond the humanities, evident in African American studies, the Effron Center for the Study of America, and the University Center for Human Values, has long been core to Princeton’s reputation for excellence.

“No humanities faculty at any institution around the world is doing it better than Princeton,” said DeLue, the University’s Christopher Binyon Sarofim ’86 Professor in American Art.

The initiative will support large interdisciplinary projects and allow the arts and humanities at Princeton “to collaborate in big, substantial ways with external partners — from the National Endowment for the Humanities to public school systems, hospitals and everything in between,” DeLue said.

To do so, the initiative will build on the strengths of the Humanities Council, expanding institutional support and structure for the humanities and ultimately absorbing the council’s functions. The goal is eventually to expand into a Humanities Institute, similar to cutting-edge interdisciplinary programs like the Omenn-Darling Bioengineering Institute and the Effron Center.

“There’s a popular vision of what the humanities is like that goes back to a monk sitting in a cell with a book by themselves. But most humanistic scholarship isn’t like that,” said Dean of the College Michael Gordin, the Rosengarten Professor of Modern and Contemporary History. “You do spend a lot of time alone, a lot of time writing and thinking and reading, but you also spend a huge amount of time in conversation with other people and in particular cross-pollinating ideas and methodologies from one field to the other.

“It’s important to cultivate opportunities where that can happen with greater frequency. The Humanities Initiative will do that, and naturally bring people together,” Gordin said.

The first Humanities Initiative project

To start, the Humanities Initiative is launching the project “Media and Meaning,” which will provide a model for the kind of future programming and collaboration that the Humanities Institute will stimulate. Like Graziosi’s scholarship, the project’s expansive concept of “media” will extend from the earliest human artifacts to AI and beyond, as scholars seek to understand and address what DeLue and Jarrett call the “the promises and perils” of media technologies across time.

On the drawing board are international conferences, public and scholarly workshops, new research fellowships, and curricular partnerships with K-12 schools and community colleges.

Partnerships with Princeton’s Program for Community College Engagement, the New Jersey Council for the Humanities and the New Jersey Council of County Colleges will consider humanities curricula in higher education in the state.

In March, the international academic conference “Fantasy: A Century” will examine the history and media of fantasy from the 1920s to today. Professor and Chair of German Devin Fore is co-organizing the event with Kerstin Stakemeier of the Academy of Fine Arts Nürnberg.

The visual and performing arts are one key avenue of inquiry, including support for projects like CreativeX that bring together artists, engineers and computer scientists to push the boundaries of creative expression. In its critically acclaimed project “Flock Logic,” Susan Marshall in dance and Naomi Leonard in mechanical and aerospace engineering choreographed a piece based on research about the collective decision-making principles that govern how birds flock and how fish school.

These blue-sky collaborations require substantial, intentional institutional support that simply doesn’t exist elsewhere, said CreativeX collaborator Jane Cox, a Tony Award-winning lighting designer for Broadway’s “Appropriate” and director of Princeton’s Program in Theater and Music Theater.

Cox, a professor of the practice in theater at the University’s Lewis Center for the Arts, is a member of the faculty steering group for the new Humanities Initiative. “What’s happening at Princeton is more creative than what’s happening in my very creative professional field of theater-making,” she said.

The ‘secret sauce’ of the humanities at Princeton

The Humanities Initiative strengthens and expands what already makes the humanities vibrant and distinct at Princeton.

“Princeton is both small and big,” said Dan Trueman, professor and department chair of music, also a steering group member. “It’s this incredible hybrid of a small liberal arts college with a huge research profile and a major engineering school — and the humanities are at the heart of its identity.”

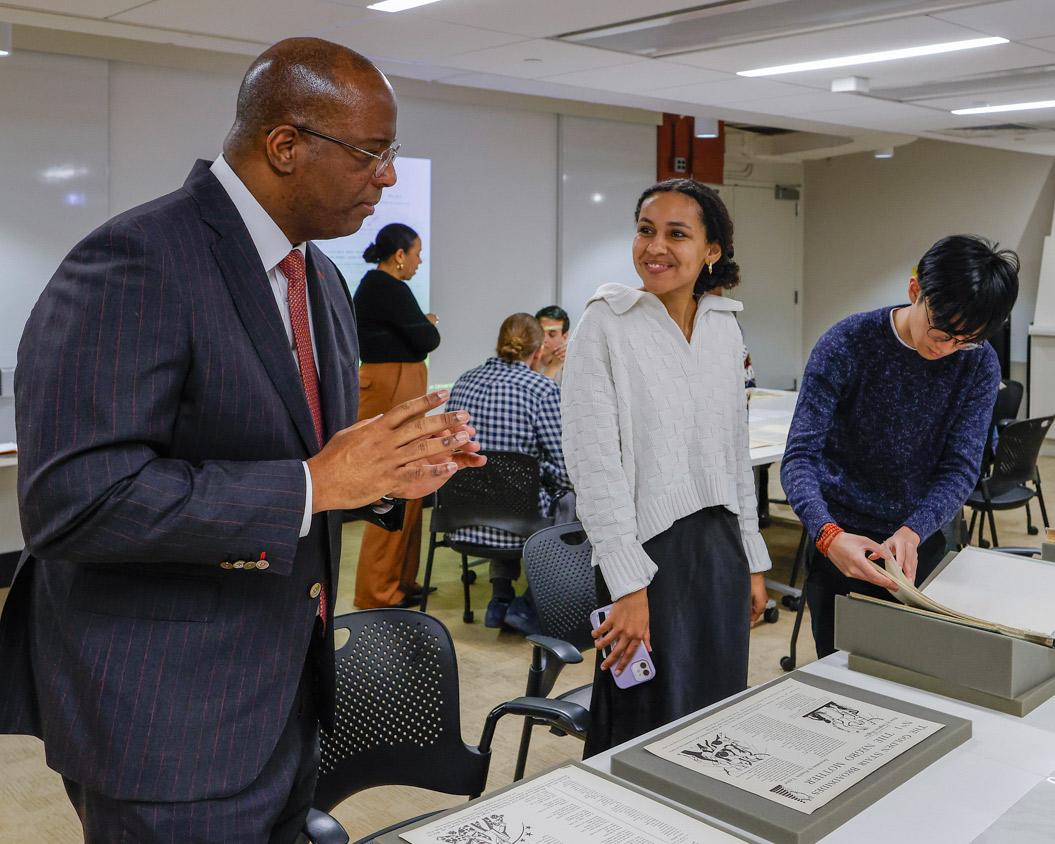

Exceptional resources for research and teaching include Princeton University Library’s Special Collections and Princeton University Art Museum, which will open a new 140,000-square-foot museum in 2025. The Center for Digital Humanities, celebrating its 10th anniversary, applies computational methods to humanities research and brings humanistic thinking to bear on ethical issues in technology.

Faculty members say they love the serendipitous connections they make simply by walking across campus, attending a colleague’s lecture or sharing a coffee, which lead to big ideas, new research and innovative courses.

“The secret sauce of the humanities at Princeton is structure — one faculty, within one community, that can create great inspiration for scholarly ideas,” Jarrett said. “We are not siloed in the ways other universities are that have many schools and faculty spread out. We’re now poised to develop, in the Humanities Initiative and then the Humanities Institute, an even more remarkable way of bringing people together.”

Melissa Lane, the Class of 1943 Professor of Politics and the former director of Princeton’s University Center on Human Values (UCHV), said the informal and formal opportunities she has had to interact with colleagues and graduate students — from classics, history, philosophy, politics and religion — have been “an intellectual seedbed” for her own work, which applies ancient political thinking to the quandaries facing modern democracies.

Princeton’s extraordinary undergraduates also spark ideas.

A math student enrolled in one of Graziosi’s undergraduate classics courses was an inspiration and close collaborator for her ancient text AI project. He introduced her to Karthik Narasimhan, associate professor of computer science and a pioneer in the technology behind ChatGPT, who became an early and important source of advice. In addition to restoring ancient texts, she is looking to add them to the corpus of AI’s large-language models.

These collaborations also ignite global impact. The new Africa World Initiative connects scholars from across the humanities, social sciences and sciences at Princeton with leaders in business, government and the arts on the African continent and globally throughout the African diaspora.

“If you study Africa just within one discipline, you end up with a limited, sometimes distorted view,” said Simon Gikandi, the Class of 1943 University Professor of English, who is originally from Kenya and is an AWI advisory board member. “When you bring people together across fields and disciplines, they share ideas and the projects they’re working on evolve as they are constantly being challenged.”

Substantive, transformative scholarship

Interdisciplinary collaboration at Princeton is encouraged by the individual strength of each humanities department, and by the depth of expertise for which they are known. “One sometimes encounters material in research that is unfamiliar and new,” DeLue said. “And the best thing is, I can get up out of my chair in my office and walk down the hall or across campus and find the person who knows the absolute most about that thing in the world.”

Humanities faculty’s deep, focused scholarship reaches across humanities disciplines, world cultures, and eras.

- Bryan Lowe, associate professor of religion, specializes in Buddhism in ancient Japan. His award-winning research, based on excavated clay pots, roof tiles, and manuscripts, offers a new way to understand how the religion took hold there.

- Lara Harb, associate professor of Near Eastern studies, focuses on classical Arabic literature. She has published and taught on the development of the aesthetic experience of wonder.

- Anne Cheng, a professor of English whose scholarship explores Asiatic femininity in western culture, is the author of the transformational book “Ornamentalism.” She is co-curating an exhibition this spring at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Kinohi Nishikawa, associate professor of English and African American studies, focuses on modern African American literature and film, book design, humor and popular culture.

- Christina Lee, professor of Spanish and Portuguese, is leading an international team of scholars in the digital restoration of a major Spanish archive housed in the Philippines that was ransacked during the British occupation of Manila in 1762.

- David Bellos, the Meredith Howland Pyne Professor of French Literature and former director of the Program in Translation and Intercultural Communication, is a renowned translator of 20th-century classics and the author of “Is That a Fish in Your Ear? Translation and the Meaning of Everything.”

- Tera Hunter, the Edwards Professor of American History and chair of the Department of African American Studies, focuses on gender, race, labor and Southern histories. Her latest book is “Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century,” and she is currently working on “The Marriage Racial Gap in the Twentieth Century.”

- AnneMarie Luijendijk, the William H. Danforth Professor of Religion, is currently working on a book called “From Gospels to Garbage,” in which she examines the readers and owners of the earliest Christian manuscripts, most of which were found on ancient garbage heaps.

- Molly Greene, professor of history and Hellenic studies, is a historian of the Ottoman Empire, with a particular focus on the history of Christians under Muslim rule and a geographic specialization in borderlands like the Mediterranean and the mountains of the Balkans.

An exhaustive list would fill volumes.

Exceptional institutional support allows Princeton faculty to burrow in and branch out as their humanistic inquiries guide them.

“At Princeton, I can fill up my pockets with ideas — and I have very deep pockets,” said Esther “Starry” Schor, the John J.F. Sherrerd ’52 University Professor and professor of English, who is chair of the Humanities Council and director of the Program in Humanistic Studies.

The Humanities Initiative will provide infrastructure and resources to bring the University’s constellation of world-leading humanists together for focused and sustained inquiry around key topics, DeLue said. “That’s the kind of big swing I’m talking about.”

Scholarship for leadership

Big swings in the humanities at Princeton reverberate across society as undergraduate and graduate alumni from all majors apply the tools of humanistic inquiry to become innovative thinkers and leaders in their chosen fields.

Humanities classes at the University brim with students from every academic discipline.

“At Princeton we are educating students who will become global leaders in lots of different fields,” said Luijendijk, who has taught at Princeton for nearly 20 years and has seen religion majors go on to pursue careers in medicine, business, environmental entrepreneurship and more.

Conversely, Princeton STEM students and social science majors pack humanities courses — “not to fulfill a distribution requirement but because there’s something there that is important to them,” Gikandi said.

Gikandi crafts literature courses with a singular focus on topics like death, evil and justice. They consistently draw students from engineering and computer science, among other disciplines, eager to grapple with these profound topics as scholars and human beings.

Courses in the medical humanities taught by associate professor Elena Fratto, a specialist in Slavic languages and literature, routinely fill with pre-med students majoring in STEM fields. Working alongside humanities majors, they consider the human dimensions of illness and disease in texts from Chekhov (who was a doctor), Tolstoy, Oliver Sacks and Kazuo Ishiguro, among others.

Simone Marchesi, a professor of French and Italian at Princeton, is a renowned expert on Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” which he has been teaching in English and Italian for more than 20 years. His classes are so popular that alumni of his Freshman Seminar and his advanced courses gather every year during the University’s Reunions to reread passages with their professor — a tradition that started with the late Princeton Dante scholar Robert Hollander.

The graduate student experience is especially rich and expansive. “The remarkable scholarship of Princeton graduate students in more than 25 different humanities degree programs creates societal knowledge that builds connections across cultures and a better understanding of our place in the world,” said Graduate School Dean Rodney Priestley.

Distinctive programs like the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities and the Graduate School’s nationally recognized GradFUTURES professional development program empower emerging scholars to become innovative future leaders in the academy and beyond. GradFUTURES offers specific sessions and support that help humanities students translate their skills and knowledge to careers in a variety of sectors.

DeLue said studying the humanities helps Princeton students understand that every action — no matter what field they go into — has an impact on human culture and society, and that every impact has consequences. “The humanities help students ask questions about the consequences, think critically about the consequences, develop ethical frameworks for their actions in the world, and consider what ultimately they want to contribute.”

The way that humanists are taught to think, study and pay exquisitely close attention to texts and works of art also fosters innovative thinking, Gordin said. “A lot of it is taking the received wisdom of the past, and then noticing, ‘Wait, there’s a gap in it. There’s something missing.’”

The process of looking for the gaps — and then learning to ask entirely new questions — “becomes a kind of muscle memory,” he said. “And students take this into the world. It becomes a habit of mind.”

This story originally appeared on the Princeton University website.