Photo by Matthew Raspanti, Office of Communications

Ten years ago, Princeton University’s Board of Trustees published a strategic framework to guide the institution into the future. As I prepared this annual letter to the community — the 10th in a series that began in 2017 — I reread the framework and the mission statement included in it.

I was struck by how well the mission statement expresses the spirit of this University. The statement affirms Princeton’s commitments to “world-class excellence across all of its departments,” to “free inquiry,” to “exceptional student aid programs … that ensure Princeton is affordable to all,” and to “welcome, support, and engage students, faculty, and staff with a broad range of backgrounds and experiences, and to encourage all members of the University community to learn from the robust expression of diverse perspectives.”

Our community’s dedication to these values has helped Princeton navigate issues foreseen in the strategic framework, such as the growing importance of technology to research universities and the world, and others we never imagined, such as a global pandemic that forced us to suspend the residential programs we cherish.

The strategic framework and the values expressed in it have shaped a period of remarkable, mission-driven growth. As I describe in the paragraphs that follow, those values will be equally crucial in the months and years to come, when changed political and economic circumstances require that we transition from a period of exceptional growth to one defined by steadfast focus on core priorities. That shift is necessary for multiple reasons, including because it will help Princeton to stand strong for its defining principles and against rising threats to academic freedom.

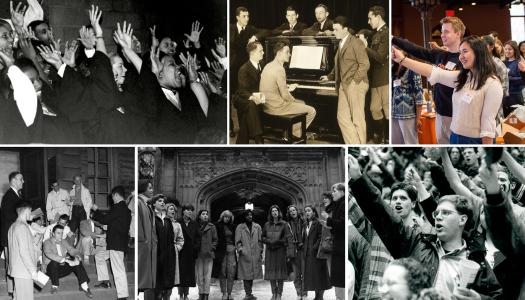

A Period of Historic Growth

The publication of Princeton’s strategic framework in 2016 laid the foundation for a historic 10-year investment in people, program, and place. We have expanded the undergraduate student body, created a new transfer program focused on military veterans and community college students, improved undergraduate financial aid and graduate fellowships, launched new academic programs and strengthened existing ones, and invested boldly in facilities that support Princeton’s academic and cocurricular programs.

The pace of construction on campus over the past five years has been among the fastest in the University’s history, culminating in a joyous ribbon-cutting phase that has spanned the last two academic years. As I noted in last year’s letter, we were “in the midst of an 18-month period in which the University will open more than a dozen substantial new facilities and spaces that enhance the University’s mission.” This period of remarkable growth is now nearly complete.

Among these recent openings are several buildings along Ivy Lane: Briger Hall, which houses the High Meadows Environmental Institute, the Department of Geosciences, and the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology; new buildings for the Omenn-Darling Bioengineering Institute and the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering; and a Commons with a library and convening spaces.

Princeton’s commitments to the physical and mental well-being of our community are manifest in the new Frist Health Center, the Class of 1986 Fitness and Wellness Center, and the Wilkinson Fitness Center in the Meadows Neighborhood. The Meadows Neighborhood is also the site of new housing that meets a critical need of our graduate student body, a racquet center that contains one of the largest convening spaces on campus, and Cynthia Lynn Paul ’94 Field, home to Princeton’s softball team.

The most energetically celebrated opening was that of the Princeton University Art Museum, which received enthusiastic reviews from the international press as well as the campus community. I wrote in last year’s letter that I expected the Museum to be “dazzling.” I would now upgrade that assessment to “magical.” If you have been inside, you know what I mean — and if not, a magnificent treat awaits you!

The Museum will bring people to Princeton who might otherwise never have visited Central New Jersey. Even more important, the Museum will transform the educational experiences available to everyone on campus. In the past, students might have graduated from Princeton without ever entering the Museum; few if any will pass it by in the future. The Museum’s exhibits will inspire at least some students to explore courses and subjects they might otherwise have overlooked. Nor need one be a student or faculty member to benefit from the Museum: its spaces of learning, beauty, and serenity are free to all.

The 2016 strategic framework, the campus plan published in 2017, and other planning initiatives laid the foundation for the recently finished facilities and the programmatic investments that accompanied them. Bringing these projects from conception to completion required skill, imagination, persistence, and hard work. I am grateful to the Princetonians throughout our community who ensured that new initiatives and facilities were thoughtfully designed, adequately resourced, and carefully constructed.

I want to add special thanks to everyone who participated — as volunteers, donors, or staff — in the recently concluded Venture Forward campaign. Venture Forward was a marvelous success by any standard; its fundraising totals were higher than any previous Princeton campaign. But Venture Forward avoided setting dollar targets: it focused on mission rather than numbers, and it emphasized engagement as well as giving.

Venture Forward’s positive impact on Princeton will be felt for generations. The additional students we have welcomed, the aid packages and graduate fellowships that we have improved, the professorships that we have added, the ribbons we have cut, and the new beginnings that we have celebrated: none of these would have been possible without the time and generosity dedicated to Princeton by loyal alumni and friends, and I am grateful to all of them.

From Growth to Focus

In this year and years to come, Princeton will continue to invest in its campus and its community of scholars and students. Hobson College remains on schedule to finish in 2027, and we are in the early stages of construction for Eric and Wendy Schmidt Hall, which will house the Department of Computer Science and related programs, and a new quantum science facility.

As I said in last year’s letter — quoting Princeton’s 17th president, William G. Bowen — Princeton is always under construction. The University must evolve to meet new challenges and extend the frontiers of knowledge.

Princeton will continue to build, but more slowly in the years to come. I expect that observation will disappoint some readers, but it may come as a relief to others who had to wend their way around multiple construction projects on the central campus over the past five years.

The change that I am describing, however, goes beyond the pace of construction. It will affect everyone on campus. Princeton will continue to evolve, but in the future it will more often have to do so through efficiency and substitution rather than addition. That will be a major change for most Princetonians, in comparison to not only the past five years but the last three decades.

The principal cause for this transition is economic. It results from lowered expectations about the University’s future endowment returns. To explain the change, I need to provide some detail about how Princeton’s endowment supports its operating budget.

As I emphasized in last year’s letter, the endowment operates like an annuity, not a savings account. The University spends around 5% of its endowment each year to support almost every aspect of its operations, including financial aid, graduate stipends, faculty and staff salaries, research equipment, construction projects, and building maintenance. (This year, the spend rate from the endowment is about 5.35%.)

The University’s reliance on its endowment has grown dramatically over time. Endowment payout provided about 15% of the University’s operating revenue in 1985. In 2016, when the Board published the University’s strategic framework, the endowment supplied 55% of Princeton’s operating revenue. Ten years later, that number stands at 65%.

Endowment dependence is mostly an enviable blessing, not a burden. It dramatically reduces our reliance on tuition and fees, thereby making both undergraduate and graduate education more affordable. The endowment also lessens the University’s exposure to variations in other revenue sources over which we have less control. But for Princeton’s financial model to succeed, the University must be able to sustain expenditures from the endowment indefinitely, for as long as the University exists. Endowment returns must be enough (on average) to cover the University’s payout and keep up with inflation.

For example, if the University spends 5% per year, and if salaries and other costs rise by 3% per year, the University’s investment earnings must exceed 8% per year on average to preserve the purchasing power of the endowment. If average earnings are higher, then that margin of return after payout and inflation can support new growth. That is the fortunate position that Princeton has enjoyed for more than three decades.

Declining Long-Term Return Expectations

Princeton needs to transition from growth to focus because long-term rates of return are steadily declining across university endowments. This decline has been hard to see because returns have been volatile. In other words, returns have not been a steady 8% or 10%; instead, they have been all over the map.

This volatility is immediately apparent from Graph 1, which shows Princeton’s annual endowment returns since 1988. For example, in FY21 the University reported a 46.9% return, the highest in its history. It appeared that the University’s financial model might have reached a new (and positive) inflection point.

Returns in the three years following FY21 were, however, among the worst that the University has had. For the first time, the University experienced consecutive years with negative returns; the three-year average over FY22-FY24 was the second worst in more than four decades, better only than the returns in the years surrounding the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-09 (and not by much).

To see long-term trends, we need to look at multiyear averages rather than single-year results. Graph 2 shows 10-year rolling averages for Princeton’s endowment returns. The 10-year average still jumps around significantly but, despite that volatility, the picture looks different (and less favorable) after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) than before it.

For example, the unprecedented 46.9% return in FY21 lifted the 10-year average to 12.7%. That number was the highest of the post-GFC period, but it was close to the bottom of the range for the 10-year average during the 17 years from FY91 to FY08. Nevertheless, the 12.7% average briefly provided some reasons for optimism about the long-term future.

If we take an even longer view by moving from 10-year to 20-year rolling averages, a much clearer pattern emerges. Graph 3 displays those averages at Princeton and several peers with large endowments. The 20-year averages slope downward across all the universities. The top of the range today is below the bottom of the range in 2005.

One of Princeton’s most famed economics teachers explained this trend in a Wall Street Journal column published last July. Burt Malkiel, the Chemical Bank Chairman’s Professor of Economics, Emeritus, described how universities have benefited from investment in long-term, illiquid assets.

When universities first adopted this strategy in the late 1980s, relatively few investors were willing to take on such illiquidity. Universities therefore had access to unusually attractive investment opportunities. Their success, however, spurred competition from others. More investors now chase a limited set of opportunities, and returns are therefore declining.[1]

Strong Foundations and Hard Choices

We have great confidence in the investment team at the Princeton University Investment Company (Princo), and Princo remains committed to generating high long-term investment returns. We believe, however, that the decline in long-term returns will persist because — for the reasons that Professor Malkiel describes, among others — they reflect changing market fundamentals, not specific investment choices. Princeton has therefore adjusted its long-term return assumptions downward to 8.0%; as recently as three years ago, we were using a 10.2% long-term assumption.

This change makes a huge difference to how we think about growth at Princeton. A 10.2% return rate can support growth in addition to covering payout and typical rates of inflation. An 8% return rate will require us to get the payout rate down below 5% even to cover payout plus inflation.

Many readers will be familiar with the powerful effects that compound interest can have on retirement accounts. The same math applies to endowments. The difference between a 10.2% and an 8% return rate is therefore very consequential. Graph 4 provides a schematic illustration of the impact. Over a 10-year period, a 2.2% reduction to expected returns would amount to a cut of more than $11 billion — a reduction that exceeds the University’s last two capital campaigns combined.

This illustration is highly simplified. When our financial and investment teams model budgetary scenarios, they incorporate market volatility, inflation, new gifts to the endowment, and other factors. They project statistical ranges of possibilities, not single points.

The simplified illustration nevertheless suffices to suggest the character of the changes we must make. The $11 billion difference between the orange bar and the blue bar represents the endowment-driven capacity for growth that Princetonians have experienced for more than three decades, and which is unlikely to recur going forward.

I want to be clear about this: Princeton continues to enjoy formidable financial and other strengths. We will sustain our commitments to excellence in teaching and research, to affordability and access, and to academic freedom and our other defining values. We will continue to seize new opportunities, though our ability to do so will be even more dependent on philanthropy than it has been in the past.

We will, however, need to pursue our mission more efficiently, including through thoughtful decisions about when to eliminate or reduce existing programs. As we emerge from a period of rapid growth, we will have to look for areas where we can consolidate or cut, both to offset rising costs (including salaries and benefits) and to support the investments required for teaching and research excellence.

In sum, Princeton has strong financial foundations and excellent opportunities, but we must nevertheless make some hard budgetary choices in the months and years to come. We will be making these changes, moreover, not in response to some dramatic, verifiable event — like the negative returns of 23.5% experienced during the Global Financial Crisis — but because of long-term trends and projections.

Could we be wrong about the projections? Of course we could. As Yogi Berra is said to have declared, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” This topic is no exception to the great sage’s wisdom.

I can, however, say three things with certainty. First, even the 8% assumption we are now using might be considered aggressive. We could be wrong in either of two directions: we might be too pessimistic, but it is also possible that we are being too optimistic.

Second, as I noted earlier, Princeton’s economic model now depends more heavily than ever on the endowment. That dependence increases the costs of undue optimism about endowment returns. If our spend rate becomes too high, the University would have to make large budget cuts rapidly, which would involve (among other actions) large-scale layoffs. We are better off making hard choices now to reduce the likelihood of even more painful actions later.

Third, we face political threats to our financial model along with the economic ones that I have discussed thus far. These challenges relate both to our endowment and our research funding, which is the University’s second largest source of revenue. Indeed, the endowment and sponsored research grants together account for 83% of Princeton’s revenue. Over the past year, we asked units across the University to make 5-7% cuts to their budgets so that we could maximize support for key priorities amidst uncertainty about federal funding, endowment taxes, and other federal policies.

That initial round of reductions was spread across the University. The long-term endowment trends described in this memorandum are likely to require more targeted, and in some cases deeper, reductions over a multiyear period. Such choices will allow the University to evolve through substitution rather than addition; they will also add to Princeton’s capacity to deal with further policy challenges or economic headwinds that may arise.

We expect that budgetary and operational changes will begin in the coming months and occur over a multiyear period. As always, we will be guided by the values and principles set out in the University’s mission statement and strategic framework, including Princeton’s commitment to maintain world-class excellence across the arts and humanities, the social sciences, the natural sciences, and engineering. Planning will be led by Provost Jen Rexford and Executive Vice President Katie Callow-Wright; they will provide information and seek input through the ordinary administrative and governance processes of this University, as well as through memoranda to the community and town halls or other gatherings.

Standing Strong for Academic Freedom

Princeton and other universities have over the past year faced a variety of threats to research funding, the immigration status of community members, free speech, academic freedom, diversity and inclusion programs, and our endowments.

Addressing these issues has been a major priority for the University and for me personally. I stepped up my work with the Association of American Universities, met more often with Washington policymakers, and sought out opportunities to communicate publicly about the principles that define this University and other great research institutions. We are in a crisis, and universities have an obligation to speak up.

While all of the issues that I have mentioned are important, universities and their leaders have a special responsibility to defend academic freedom, which is crucial to the excellence of research and teaching. The principle is sometimes conflated with free speech, but academic freedom is distinct from free speech and even more directly connected to the core mission of universities.

Academic freedom enables researchers and teachers to pursue truth and advance knowledge in their fields and disciplines. It protects scholarship and teaching from interference by government officials, university administrators, donors, and anyone else who might want to substitute their will, preferences, opinions, or judgments in the place of academic standards.

People sometimes misunderstand academic freedom as allowing professors to say or do whatever they like. That is a mistake. Academic freedom does not insulate scholars from evaluation or accountability. On the contrary, it depends upon and presupposes a rigorous system for evaluating the quality of research.

Scholars‘ work is and must be judged all the time: when they submit articles for publication, when they seek appointment or promotion, and when they apply for funding from the government or other sponsors.

The point of academic freedom is not that scholars should be free to say what they like; it is instead that scholarly work should be evaluated through the good-faith application of academic norms and standards, not on the basis of what somebody in power — at the university or outside it — would like to hear.

The connection to academic standards, and to scholarly responsibility, explains why academic freedom is simultaneously distinct from free speech and more fundamental to what universities do.

Free speech rights permit everyone to express opinions, regardless of how those opinions were derived or how qualified the speaker is to pronounce them. They govern controversies like the ones about outside speakers and campus protests at colleges across the nation that have attracted so much attention in recent years.

Academic freedom, by contrast, recognizes the right and the responsibility of scholars to investigate questions and express judgments about matters within the scope of their learning and fields of research.

Free speech and academic freedom are complementary principles; both are essential to the life of a great university. It is academic freedom, however, that ultimately guarantees faculty members here and elsewhere the freedom to seek knowledge even when doing so may anger officials, disrupt industries, upset orthodoxies, or inflame controversies.

Research universities depend upon the capacity to pursue uncomfortable truths and publish controversial ideas. American universities have become world leaders in no small part because they have insisted on academic freedom and because our governments have, for the most part, respected it. If universities cede that right, they compromise not only their own missions but also the vital contributions they make to our country’s health, culture, prosperity, and security.

I have accordingly been heartened by the strong support that Princeton faculty, students, staff, and alumni have given to academic freedom and higher education as part of our Stand Up for Princeton and Higher Education initiative. Your voices make a difference.

I am grateful for your partnership on academic freedom and so many other issues. You have strengthened this University at a time when its mission and values are more important than ever. Continued engagement and collaboration will be essential as we confront the challenges that I have described in this letter.

Finally, I promised in last year’s letter to publish annually data that we collect through periodic surveys of our students and which helps us track progress toward our goals. The most recently updated data is available as an appendix to this letter.

I look forward to working with you as we build upon recent progress and carry forward this University’s mission of scholarship, teaching, research, and service.

[1] Burton G. Malkiel, “Diminishing Returns for University Endowments,” The Wall Street Journal (July 6, 2025).

A version of this story was first published on the University webpage of the Office of the President.