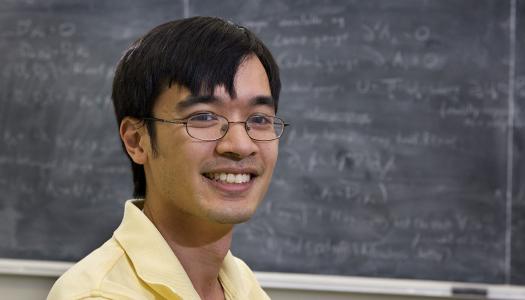

Policy and civic discourse: Princeton helped prepare Kevin Gover ’78 for transformative public service

Photo: Noah Willman Photography

It was the early 1960s and the times they were a-changin’ on the Great Plains in Lawton, Oklahoma — just as they were across the United States, with the Civil Rights Movement shaking the status quo. Kevin Gover was watching and listening, a kid “hanging around the fringes” of movement meetings he attended with his parents.

He noticed at these meetings that whenever the lawyers in the room spoke, “everybody listened.” It was just like the rapt courtrooms of the “awesome” fictional criminal-defense attorney Perry Mason, a show he watched without fail on CBS prime time.

“To tell you the truth, I had no idea then what lawyers did,” he said. “But I knew I wanted to be one.”

Gover followed his dream from Oklahoma to Princeton, and then on to a law degree from the University of New Mexico School of Law. Today, as under secretary for museums and culture at the Smithsonian Institution, he oversees an expansive portfolio of museums of history and art, cultural centers, and the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Exhibits, and the National Collections Program.

Gover also followed in his parents‘ footsteps in social activism and public service. Speaking on a panel of alumni at St. Paul’s School in 2023 about what it means to live a life of service, Gover, a member of the Pawnee Tribe, noted that the driving force behind his career was a cause: the empowerment of Native American tribes.

As an attorney, he became a renowned authority on tribal governance: he worked in Washington, D.C., at the nation’s largest firm practicing Indian law, and then, in 1986, founded in Albuquerque what would become the largest Native American-owned law firm in the country, representing tribal nations. From 2003 to 2007, he taught federal-Indian law at the Sandra Day O’Connor School of Law at Arizona State University.

Through high-profile public service roles, he’s led policies and designed programs that promote cultural understanding and empower communities to tell their own stories. He served as assistant secretary for Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior during the Clinton administration (1997-2001) and was director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) for 14 years before taking on his current role in 2021.

His opinion pieces published in national newspapers have helped shape national conversations about identity, including a 2017 article in The Washington Post, “Five Myths About American Indians,” in which Gover dispelled the notion that “Native Americans” is the only proper term for the nation’s Indigenous people (“Native Americans use a range of words to describe themselves, and all are appropriate”) and spoke out against the use of Native American mascots for sports teams, citing the “harmful effects of racial stereotyping on the social identity and self-esteem of American Indian youth.”

On Feb. 21, Gover will receive Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson Award, bestowed annually on an undergraduate alumnae or alumnus whose career embodies the call to duty in Wilson’s 1896 speech, “Princeton in the Nation’s Service.”

“Through his extraordinary work as a lawyer, a scholar, a high-ranking government official, and a leader of the Smithsonian museums, Kevin Gover has helped to build a more inclusive America,” said President Christopher L. Eisgruber ’83, in the University’s announcement of the award. “Every day the Smithsonian museums spark new conversations about who we are and who we can be as a people, and Kevin’s thoughtful dedication is crucial to our collective understanding of what America means as it celebrates its 250th anniversary next year.”

As Gover has navigated a career with remarkable accomplishments, he’s leaned into what he learned at Princeton, where he earned his undergraduate degree in public and international affairs.

Those days at Princeton, he said, were deeply formative — though they came with their own set of challenges.

Princeton days: Policy and protest

Princeton was full of wonderful academic surprises for Gover. He fondly remembers a class on Shakespeare that typically ended with applause for the professor’s dramatic readings of the Bard’s work and an engaging professor who taught “Physics for Poets” and sparked his curiosity in science.

Policy classes at what is now the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs had a lasting impact. Decades later, when he took on the role as head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), Gover worried he might be out of his element. He’d practiced as a lawyer for more than a decade and knew his field, but “running a government agency, that was a whole different thing.” He quickly realized, though, that it wasn’t about the mechanics of the agency: “It was a policy job. And Princeton had prepared me as well as one can be prepared for these things.”

In Princeton’s classrooms, professors challenged him to look at a problem from as many perspectives as possible. He learned that “sometimes there’s no good outcome. You have to make choices about the greatest good for the greatest number.” He also learned the rigor and necessity of civic discourse — how to listen closely, argue carefully and engage respectfully across differences. One class on South African history, for example, was taught by a professor Gover often disagreed with, but deeply respected. “I appreciated the opportunity to sharpen my understanding with somebody who didn’t necessarily share my overall view of the situation,” Gover said.

When he wasn’t in the classroom, though, Gover said that he felt like an outsider during his time on campus, despite arriving at Princeton with friends from St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire.

“It’s nobody’s particular fault,” he said. “I think the University was just in the early stages of integrating and the early days of co-education, and I think they didn’t know what they had gotten themselves into. We didn’t feel like the tip of the spear, but we were in those early years.”

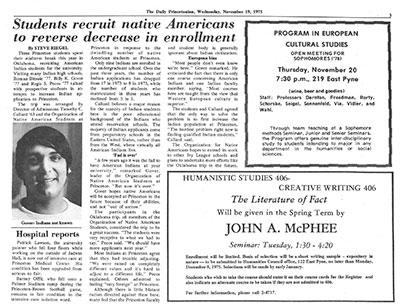

Gover was not discouraged by his outsider status; rather, he was motivated by it to advocate for change. He wrote opinion pieces for The Daily Princetonian — including one arguing against budget cuts to the Third World Center (now the Carl A. Fields Center for Equality + Understanding), where he served on the governance board. In November 1976, the Daily Princetonian ran his letter to the chair of the Board of Trustees about upcoming tuition increases: “Any further tuition increases will jeopardize Princeton’s future as surely as it will close the University’s doors to middle- and low-income people.”

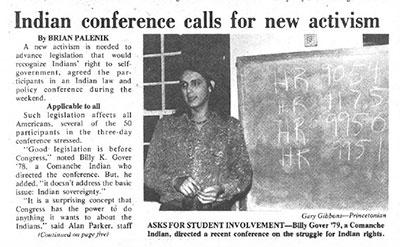

A score of articles in the Daily Princetonian catalog some of his other activities, including a 1975 trip to Oklahoma arranged by the Admission department to recruit American Indian students for the University and a three-day Indian law and policy conference in November 1977 directed by Gover with the goal to “expose the non-Indian community to what concerns us.”

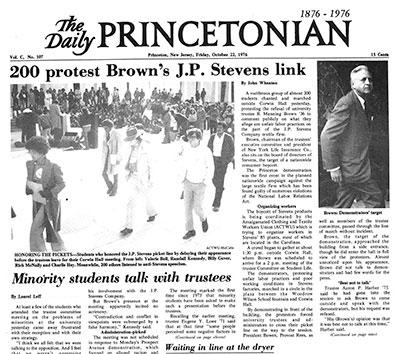

Daily Princetonian articles also document Gover’s attendance at student protests, most notably an April 1978 demonstration on Cannon Green protesting the University’s stock holdings in corporations doing business in South Africa. More than 800 students marched in the April protest calling for divestment; according to that year’s Nassau Herald: “For many, the most moving moment … came when … Gover gave a speech about the United States‘ own form of apartheid — directed against Native Americans.”

Leading through service: ‘The less I wanted, the more I got’

When Gover was selected by President Clinton for the top post at BIA, naysayers immediately surfaced, warning him it was the worst job in the government — a position where it would be impossible to succeed.

But Gover listened for more views — and heard the many Native people who said they were praying for him, bolstering his belief that the work he would be doing was meaningful. He also focused on achievable goals: “We kept doing the thing that was in front of us: What’s the next step? And we had some successes.”

The successes were significant, including getting Congress to appropriate more funding for the 185 BIA-run Indian schools, which then had a $700 million backlog in health- and safety-related repairs, improvements and maintenance. As Gover said in a statement through BIA’s Office of Public Affairs in 2000, “Our children have been attending schools in buildings that are dangerous, and this must stop.”

Clinton’s FY01 budget included $300 million for school construction and repair — more than double the previous year’s funding, and authorized Gover to allocate $400 million in bonding authority for the construction and renovation of the schools.

Another win in the FY01 budget was increased funding for law enforcement in Indian country. A joint report between the Department of Justice and the Department of the Interior had shown law enforcement received only about one-fourth the resources of most rural law enforcement agencies. “Being a tribal cop, you’re always under-resourced, you’re always understaffed and you’re living among people who are struggling,” Gover said.

Gover also made headlines during his three years at the BIA for a public apology he made, on behalf of the agency, to the tribes for a history of federal “ethnic cleansing and cultural annihilation” policies, including the boarding schools that were established on the motto of their founder, Richard Henry Pratt, who said in 1892, “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Tens of thousands of Indian children were removed from their families and forced to attend these schools, where they were forbidden from speaking their languages and made to abandon their cultures. At an event on Sept. 18, 2000, commemorating the 175th founding of the BIA, Gover stated, “These wrongs must be acknowledged if the healing is to begin.”

Reflecting today on the apology, Gover said, “It was partly that sort of a cleansing that needed to happen, but it was also us laying claim to [the BIA] and saying, ’This is our agency now. Ours, the Native peoples‘. And that’s who we serve.’”

The leadership role at BIA wasn’t something he had planned for. “I had no such aspirations,” Gover said. “Some of the best things that have happened to me have happened not because I was looking for them. The less I wanted, the more I got.”

In 2007, he became the director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, D.C., and its George Gustav Heye Center in New York City. “I could see the power of the platform and the power of the Smithsonian brand really gave us an opportunity — not to shape the narrative [because] the narrative was well-known to the tribes — but to bring it to a larger audience with the imprimatur of the Smithsonian behind it,” he said.

Gover oversaw numerous critically acclaimed exhibitions that expanded public knowledge of the launch of Native Knowledge 360°, a national education initiative providing resources, training and materials to transform K-12 teaching about Native Americans.

The museum also took on the issue of Native American mascots at colleges and high schools and professional teams, hosting a symposium in 2013, “Racist Stereotypes and Cultural Appropriation in American Sports.” “When the Washington football team changed its name [in 2020], I felt very good about that,” he said.

Gover also supervised the creation of the National Native American Veterans Memorial, which opened in November 2020 on the grounds of NMAI. Congress authorized the memorial, but mandated that no federal funds be used in its construction.

“I had to rely on a handful of staff who were not federal employees,” Gover said. “It became a passion project for us all. Talk about rewarding. We met all these wonderful veterans … We had to go out and raise the money for it, but all of the tribes know the military tradition of Native people serving in the armed forces. And so it required some effort, but we always knew we were going to be able to find the support.”

Native Americans have served in the U.S. military in every major conflict for 200 years. Perhaps their best-known contribution has been as code talkers in World War I and II, using languages they’d been punished for speaking as children to create unbreakable complex codes.

“The place the tribes have made for themselves in the society, in part through service to the United States, is well earned,” said Gover. “You’ll find no greater patriots, frankly.”

Patriotism runs deep in Gover’s own family, which includes many veterans. His grandfather served in the Army as a code talker in World War II and lost an arm fighting near Monte Cassino in Italy.

Today: Leadership at the intersection of history, culture and public life

In his current role at the Smithsonian Institution, a complex network of museums and cultural initiatives that reach millions of visitors and students each year, Gover helps meet priorities around historical complexity and cultural representation.

“It appeals to my great interest and affinity for working on policy,” Gover said. “It’s one thing to run a museum, to make day-to-day decisions, but to talk about the overall policy of the Smithsonian is another thing.”

Among many accomplishments, he’s helped to develop the Smithsonian’s ethical returns and shared stewardship policy, looking at issues of provenance, ownership and cultural heritage of art and artifacts. “It’s a question of morality,” he said. “How did our museum come to possess these things, and is that right?”

For example, in October 2022, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art transferred ownership of 29 Benin bronzes, stolen during an 1897 British raid on Benin City, to the National Commission for Museums and Monuments in Nigeria.

Gover’s current work at the Smithsonian is meaningful to him because it focuses on allowing people to tell their own stories across the museums’ exhibitions and programming, and on encouraging contributions from a wide range of viewpoints. “It’s really a powerful relationship between this gigantic institution and these small communities,” he said.

He also heads a committee that ensures that content is accessible to “a diversity of perspectives,” he said. The work reminds him of his days in Princeton classrooms discovering the value of civic discourse, “relying on more than rhetoric and overstatement.”

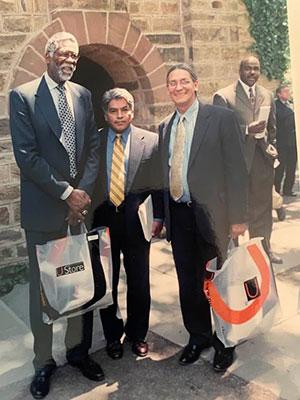

Alumni Day will not be the first time the University has recognized Gover for his public service. In 2001, just after his time at the Department of the Interior, he was honored for his leadership and contributions to public policy, tribal advocacy and the administration of Indian affairs. At that year’s Commencement, standing next to fellow honorees, including Sonia Sotomayor ’76, basketball icon Bill Russell and filmmaker Spike Lee, he became the first Native American to receive an honorary degree from the University.

The official citation read, in part, “As an undergraduate he marched on this very ground with placards drawing attention to the plight of the American Indian … His career, marked by the courage of his Pawnee and Comanche ancestors, is a model for the members of the 562 American Indian Nations and for all Americans of a life led ‘in the nation’s service and in the service of all nations.’”

“That was a surprise, as is this award,” Gover said. He is “genuinely touched and honored” to receive the Woodrow Wilson Award and is looking forward to sharing with alumni and friends some of the many stories of his career in public service. “It’s always nice to have your efforts acknowledged,” he said, “even if that’s not why you do the work.”