Asset Appreciation: Emeritus Professor Ken Boudreaux ’65 creates gift for a future economics professor

Kenneth Boudreaux ’65 didn’t expect to come east from New Orleans for college. He didn’t expect to run a laundry delivery service as a senior, or that his career path would lead to becoming a college professor.

But life held all these experiences for Boudreaux, who is a consulting economist for commercial, employment and personal injury cases after 30 years teaching at Tulane University. In gratitude for the professors who helped guide him as an undergraduate, he has planned in his estate for the creation of a professorship in the field that he discovered an affinity for at Princeton: financial economics.

Inspiring Educators

An introductory finance course with Burton Malkiel *64, now the Chemical Bank Chairman’s Professor of Economics Emeritus, sealed Boudreaux’s choice of major. “I just loved it,” Boudreaux remembered. “He (Malkiel) was a wonderful lecturer. And that really hooked me.”

In addition to Malkiel, Princeton’s economics faculty included several noted practitioners: William J. Baumol; Fritz Machlup, the Walker Professor of Economics and International Finance; and Oskar Morgenstern. Morgenstern, revered to this day for his work on modern-day game theory, oversaw Boudreaux’s senior thesis.

The field of financial economics at that time, Boudreaux said, was advancing portfolio theory — a theory to minimize an investor’s risk — and models for pricing risky securities and figuring the expected returns for assets.

“Princeton’s economics faculty was absolutely the best that you could find, particularly with respect to financial dimensions,” Boudreaux said. “And that was strange, because without a business school, you would be surprised that there would be offerings in finance … It was an education that was memorable. In retrospect, it really has been a wonderful background to point to.”

Candling Eggs, Delivering Laundry

An assistant preacher at church suggested Princeton and paid the application fee for Boudreaux; the minister was a Princeton graduate. Boudreaux, like many classmates on financial aid then, worked in the cafeteria during his first and second years but then took on more colorful jobs.

As a junior he assisted with an egg business that was walking distance from campus, first with candling — the method used to check raw eggs for embryos by holding them over a candle — then delivering the eggs to the eating clubs and other facilities on campus and around Princeton.

He was a member of Cannon Club, and Cannon had a connection with the laundry service on campus. Two seniors ran the service each year, and earned a commission for driving the truck. “You had to start at about 2 or 3 in the afternoon, every afternoon,” Boudreaux said, “so you had to schedule your classes to deal with that. And you’d have to go to every dormitory and every entryway on campus at least two or three times a week to do the pickups and collections. I think it helped me in terms of scheduling my life. And senior year, I was one of the wealthiest guys in the club because of my commission off the laundry.”

After Princeton, by staying in school he was able to skip the hard choices a lot of his classmates had to make in the late ’60s. He earned his MBA from Tulane in 1967. Then, intrigued by a paper on the capital asset pricing model, Boudreaux went to the University of Washington, where future Nobel laureate William Sharpe was then teaching, to earn his Ph.D. He landed back in his hometown, teaching at Tulane.

Giving Back

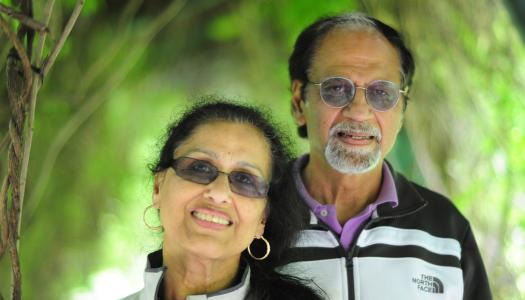

Boudreaux became a 1746 Society member by adding Princeton to his estate plan. He and his wife, Carole, have also made gifts to Tulane as part of their legacy planning. It was a process over several years to determine the best course, he said.

After his long career in financial economics, he has this advice for others:

“You get to the point where you have to make some decisions. We decided it’s better to do it now than have it done by someone else, or when we’re feeling under pressure and maybe don’t have the capabilities to give as much thought and effort as we do now. That’s the reason we started about two, three years ago saying, ‘Okay, now we have to start deciding what’s going to happen to all this.’ That’s a process, and Princeton has been very good in helping me along with it.”

For Boudreaux, extraordinary teachers inspired his gift of a professorship that circles back to his academic beginnings while helping to ensure a similar experience for future Princeton students.