From Eno Hall to Peru to eBird, John Fitzpatrick *78 helped lead the field of ornithology to new heights

Courtesy John Fitzpatrick

A flick of wings. The flutter of a heart. When a black-and-orange bird perched at eye level in a tree outside a home in the countryside near Saint Paul, Minnesota, little did the boy inside who spied it suspect that this chance encounter would lead to a revolution in birdwatching and conservation.

John Fitzpatrick *78, known today as “North America’s most prominent ornithologist,” was supposed to be in kindergarten that day, but feeling unwell, he was instead gazing out the window at what he thought might be an oriole. Fortunately, his illness had zero effect on his curiosity. The precocious future scientist thumbed through his parents’ field guide to identify the visitor, which turned out to be an American redstart. He distinctly remembers the feeling as he flipped wide-eyed through the pages: “It was like, look at them all. I want to see all these birds.”

As luck would have it, he lived in a neighborhood with several adult birders who nurtured his enthusiasm. Among them was Francis Lee Jaques, a famous wildlife artist who had recently retired from the American Museum of Natural History. “He was a wonderful artist and a wonderful man who loved telling stories of his expeditionary days,” Fitzpatrick said. Jaques inspired the boy to draw, and painting birds became a lifelong passion.

By age 6, Fitzpatrick participated in his first Christmas Bird Count, a citizen-science, census-taking conservation effort organized by the National Audubon Society. Two years later, his parents gave him a vinyl record of birdsongs, published by Cornell University’s Laboratory of Ornithology, which he listened to repeatedly. In his undergraduate years at Harvard College, he realized that his passion for birds created a potential career path. He studied biology and fell in with avian experts at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, assisting their research by identifying and cataloguing South American flycatchers from a recent expedition.

“I learned in college that scientific ornithology was a possibility,” said Fitzpatrick. “I thought, ‘This is what I’m going to try to do. I’ll take it as far as I can, and if it stops at some point, then I’ll just become a beekeeper.’”

It never stopped. And the field of ornithology has never been the same.

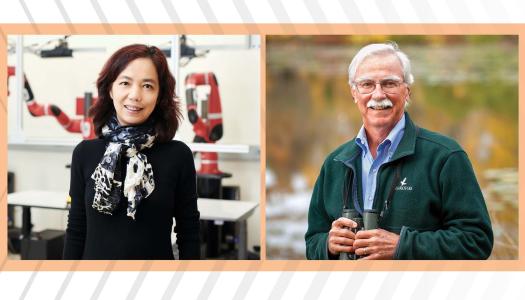

On Feb. 24, Fitzpatrick will be honored with the James Madison Medal, given annually on Alumni Day to celebrate a Princeton alumna or alumnus of the Graduate School who has had a distinguished career, advanced the cause of graduate education or achieved an outstanding record of public service.

Fitzpatrick has soared in all three areas. His career has included prominent positions at the Field Museum in Chicago, Archbold Biological Station in Florida and Cornell University, where as the Louis Agassiz Fuertes Executive Director at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology from 1995 to 2021, he led the nonprofit organization and research facility to become a global leader for research, education and conservation of birds. Most famously, he guided the Cornell Lab in the launch of eBird, a citizen-science project that is a global game-changer for birdwatching and biodiversity conservation.

To appreciate the heights of Fitzpatrick’s career, it’s helpful to revisit his Graduate School years. His Princeton experience was key to his future, and it almost didn’t happen.

Spreading His Wings

John Terborgh, a professor of biology at Princeton and a rising star in tropical ecology, was studying birds in the Andes of Peru when he visited Harvard in 1973 to give a presentation to a small-group seminar. “His talk totally blew me away in terms of how really cool the work was — impressive, prodigious field work that was theoretically based,” Fitzpatrick said.

At lunch afterward, “he and I were gabbing about South American birds,” said Fitzpatrick, who was studying tody-flycatchers for his senior honors thesis. He told Terborgh that he had a fellowship lined up at Berkeley to continue his work. Terborgh asked why he’d chosen Berkeley. “I said, ‘Ned Johnson’s there. He’s a flycatcher expert,’” Fitzpatrick said. “And he said, ‘Yeah, but Ned Johnson doesn’t work in South America.’”

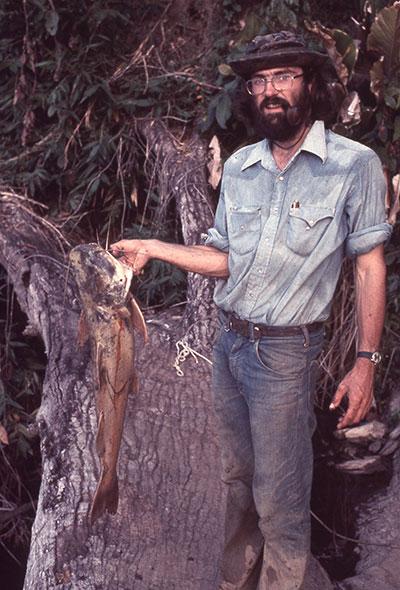

Terborgh, on the other hand, was headed that summer to the newly established Manú National Park in southeastern Peru where he was setting up a biological research station, Cocha Cashu. He dangled an opportunity: one to see all the birds. “‘Why don’t you come down with me to Peru?’ he asked me,” said Fitzpatrick. “‘Why don’t you apply to Princeton?’”

Cocha Cashu was unlike any other place in the world. Almost undisturbed by human activity, it was reached by two to three days’ travel by truck from the city of Cusco and then a day upstream in a dugout canoe. For a birder, it was heaven. “It was certainly among the places with the greatest biodiversity on the planet,” said David Willard *75, ornithologist and collections manager emeritus at the Field Museum, who studied the huge community of fish-eating birds at Cocha Cashu.

The two first met when Fitzpatrick visited the population biology group at Princeton’s Eno Hall in January 1974, just a few weeks after that lunch with Terborgh. Fitzpatrick found the biology department thrumming with energy. Professors, including Terborgh, Henry Horn and Robert May were carrying on the legacy of Robert MacArthur, who had come to Princeton in 1965 and put the department at the forefront of innovation as he founded the field of evolutionary ecology. Although the groundbreaking scientist tragically had died in 1972 at the age of 42, “MacArthur was literally still in the air,” Fitzpatrick said of his visit. “He was in everybody’s conversation.”

The pull was irresistible for Fitzpatrick. Within a few weeks he applied to Princeton and was accepted. He skipped his Harvard graduation ceremony to join Terborgh and three others in Cocha Cashu. After figuring out how to manage the intricacies of Peruvian permitting, the group spent about two and a half months cutting trails, laying delicate mist nets to safely capture birds, sleeping in tents, and, most important, observing flora and fauna in a tropical paradise previously unseen by scientists.

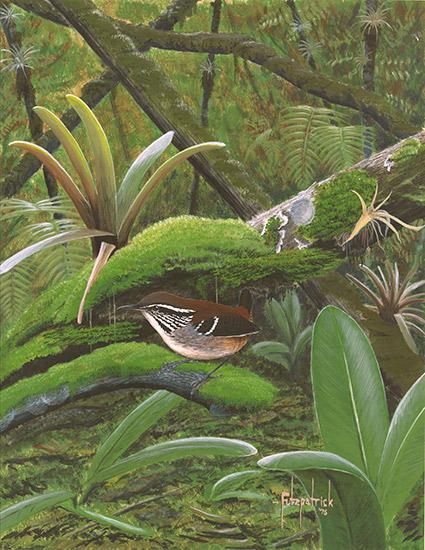

Fitzpatrick did most of his graduate field work in Peru, but also worked in Brazil, Venezuela and Central America. In two expeditions to northern Peru in 1975 and 1976, he and his team, including Willard, discovered five species of birds that were new to science, including the bar-winged wood-wren.

Fitzpatrick credits Terborgh for mentorship that went far beyond providing the opportunity to see birds. “During that first summer in Peru, Terborgh advised, ‘Don’t worry about your Ph.D. thesis right now. Just be observing and thinking every day about what seems really interesting to measure,’” Fitzpatrick said. “Science is about measurements, ultimately, and ecology is about getting lots of measurements. I later developed my own phrase for our discipline: ‘If you haven’t gotten bored doing fieldwork, you haven’t done enough of it.’”

Another phrase he heard often at Princeton inspired him: “It’s the question that is the difficult part.” The quote might have originated with MacArthur, “but it was repeated by everybody there,” Fitzpatrick said. “In our field of ecology and evolutionary biology, the fieldwork part — the actual measurements, the physical process — is relatively straightforward, easily described. The challenge is deciding what’s a really interesting and novel question that’s going to open up new ideas about how nature works.”

Fitzpatrick’s Ph.D. dissertation was a survey of the 400 or so species of tyrant flycatchers (Tyrannidae), the largest family of birds in the world. The work involved quantifying their foraging behavior and comparing it to their body forms, species by species, and then developing mathematical models that would offer insights to the family’s behavioral and structural evolution.

Scott Robinson *84, the Katharine Ordway Professor of Ecosystem Conservation at the University of Florida Museum of Natural History and a fellow Terborgh advisee, first met Fitzpatrick in 1976 at a gathering of ornithologists in California; in 2019, the two longtime friends and colleagues returned to Cocha Cashu together for research. Robinson said Fitzpatrick’s thesis work was unprecedented, citing the huge amount of data he collected from a large and diverse species pool dominated by “extremely elusive” birds. “Nobody had any data on these birds,” said Robinson. “There’s still nothing that’s been done that’s comparable to it.”

Collecting behavioral information on such a diverse population in the Amazon rainforest was ambitious and required, among other traits, “lots and lots of patience,” said Willard, who noted that birds under observation often suddenly disappeared into the trees. It also demanded a high threshold for risk. Willard recalls a day when Fitzpatrick was working from a canoe, and a jaguar settled onto a nearby limb to observe him.

But for Fitzpatrick, the many trips into the wild were never about the thrill of adventure. “I’m willing to tolerate adventure if I have to, but this was not about seeking adventure for its own sake,” Fitzpatrick said. “It was genuine fundamental human curiosity about the evolutionary biology of this amazingly cool, very large radiation of birds.”

Career Migrations

After Princeton, Fitzpatrick worked at the Field Museum in Chicago for 12 years, starting as a curator, rising to the chair of the zoology department, and continually returning to South and Central America for research. In 1988, pursuing what had been a parallel research path since his Princeton days, he left Chicago to become executive director of the Archbold Biological Station in Venus, Florida, establishing a major agro-ecology research program on a nearby ranch and devoting himself to the ecology and conservation of the endangered Florida scrub-jay and its embattled habitat. Fitzpatrick worked to establish a national wildlife refuge to protect the Florida oak scrub habitat, and once even put himself in front of a development company’s bulldozer — armed with just a first-generation video camera — until the driver gave up and rambled away.

Fitzpatrick affectionately calls the Florida scrub-jay “his bird.” Because they are all individually color-banded, he can say with certainty that he has known every single scrub-jay at Archbold going back 17 or 18 generations. The relationship began in April 1972 when he visited Archbold as a college intern. He has returned every April since as part of the annual effort to map the birds’ territories — except 2020, when the pandemic kept him from the work.

Robinson said Fitzpatrick’s studies at Archbold, which established links between the birds’ cooperative breeding (youngsters help raise the next generation) and their limited habitat availability, are examples of how Fitzpatrick helped advance the field of behavioral ecology to “the next level.”

In 1994, when Cornell University approached Fitzpatrick about becoming director of its Lab of Ornithology, a research center that dates back to 1915, he told the dean he’d take it only if Cornell agreed to significant growth. While he couldn’t predict where science and technology would go, he saw the need for at least five professors, each ambitiously leading labs in distinct areas that supply leadership-level opportunities in science, education and conservation. At the time, there were just two such labs.

Fitzpatrick committed himself to raising the money for two of the additional professorships, on condition that Cornell supplied the fifth. This act underscored one of his core beliefs. “If money is the only thing keeping you from getting important things done, then you’ve solved all the hard problems,” he said. “If it’s a truly good idea, and you have a vision for how it would work, then there’s money for it out there somewhere.”

Fitzpatrick’s vision for the Cornell Lab continued to grow. In 1996, Fitzpatrick shared an idea with fellow ornithologist Frank Gill, then at National Audubon: to use the internet and emerging technologies to capture the data of citizen-science bird enthusiasts like those who participate in censuses like the Christmas Count and Project FeederWatch. The first-iteration result was BirdSource, a Cornell-Audubon digital platform that represented proof-of-concept. Soon after, Fitzpatrick and his colleagues secured crucial start-up funding that allowed the Cornell Lab to take over all the operations. “After a couple of tries,” Fitzpatrick said, “we got this major NSF grant that gave us the money to rebuild and really start this thing, which later became a whole enterprise called eBird.”

The site launched in 2002. The idea behind eBird is simple: birders fill out online, real-time digital checklists of which species they observe and how many of each, and document exactly where and when they birded. As mobile technology has rapidly improved and interest in birding has surged, the data collected globally has exploded: eBird now documents well over 100 million bird sightings each year. It’s one of the world’s largest biodiversity-related science projects and its far-reaching applications stretch from research and monitoring to species management, habitat protection, and even informing policy and law.

“It revolutionized everything about birdwatching,” said Robinson, adding that for many, like him, “eBird’s addictive.”

The platform’s enormous digital database also drives Cornell Lab’s machine learning-powered Merlin Bird ID tool, which took flight in 2014 and provides an easy and engaging way to recognize and connect with birds. Together, eBird and Merlin harness what Fitzpatrick has come to call “the power of birds.”

“Birds make us pay attention to nature unlike any other single group of organisms,” he said. “They fly, which is a powerful thing. They migrate by the billions twice a year, so they’re the heartbeat of the annual cycle. They’re also very, very sensitive environmental indicators, and famously so in cases like the peregrine falcon and others, where we’ve learned some things about what we were doing to ourselves as result of the changes our activities were causing in bird populations. And maybe most important, everybody loves them!”

A New Flight Path

In June, Fitzpatrick will retire from his position as professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Cornell, but he plans to continue his lifelong study of birds. His Florida home, where he and his wife, Molly, live part-time, is near his beloved scrub-jays and he’ll continue to support and study them while keeping his oar in the water in global biodiversity conservation efforts.

In whatever time he can spare, he also hopes to focus on his artwork. Over the decades, he’s created an impressive collection of paintings, beautiful tributes to the birds that have kept his heart fluttering and his mind stimulated with curiosity. “I’m looking forward to doing some more watercolors,” he said, humbly adding, “and actually, it’s been a long time since my days at Mr. Jaques’s knee. I want to finally get somebody to teach me all the things about painting I wish I knew about, or at least some of them.”

Meanwhile, Fitzpatrick is also looking forward to returning to Princeton on Alumni Day and is grateful for his place in the University’s history.

“I know it’s the first time they’ve given the award to an ornithologist,” he said. “Princeton has an extremely illustrious history in the whole field of ecology and environmental biology, and I feel honored and privileged to be the first to have earned this award in our field, because it’s a really important part of what Princeton does as a university. Quite literally, I stand on the shoulders of giants, of Princetonian giants.”

Alumni awards and accompanying lectures will be presented in Richardson Auditorium during Alumni Day ceremonies that also will recognize student winners of the Jacobus Fellowship and Pyne Prize. The Alumni Day program will also feature the annual Alumni Association luncheon at Jadwin Gymnasium and the Service of Remembrance at the Princeton Chapel, honoring alumni, students, and members of the Princeton University faculty and staff whose deaths were recorded by the University in 2023. Pre-registration is required.