Photo by Denise Applewhite, Office of Communications

President’s Annual ‘State of the University’ Letter 2024: Excellence, Inclusivity and Free Speech

Seven years ago, I began writing annual letters on the state of the University, its progress toward strategic goals, and major issues relevant to our mission and higher education more broadly. This report is the eighth in that series, and Princeton is stronger than ever.

We persisted successfully through the recent pandemic, and our campus again hums with energy. We have in the last two years made historic improvements to graduate student stipends, undergraduate financial aid, and postdoc salaries. We have expanded our undergraduate student body and increased its socioeconomic diversity. We have added a new and vibrant transfer program focused on community college students and military veterans.

The University’s faculty continues to produce pathbreaking scholarship, a fact reflected in the many honors and prizes that our professors collect. Just last month, we announced plans to establish an artificial intelligence hub for New Jersey in partnership with Governor Phil Murphy and the New Jersey Economic Development Authority.

Princeton is also in the midst of an intense period of campus construction driven by the University’s strategic framework and facilitated by the tremendous success of the Venture Forward campaign. With the opening of Yeh College and New College West for the 2022-23 academic year, our community began to enjoy the fruits of that investment.

Those benefits will accelerate in the coming months. Over the next two years, we will cut the ribbons on new housing units for graduate students and postdocs, the Omenn-Darling Bioengineering Institute, a new art museum, a new environmental sciences building, the Class of 1986 Fitness and Wellness Center, the Frist Health Center, and a renovated Prospect House, among other projects.

At the same time, however, Princeton and its peers confront a challenging political landscape that demands the attention of anyone who cares about higher education. During the past year, we have seen increasingly virulent threats to academic freedom and institutional autonomy, two core principles that have made America’s universities the envy of the world.

Antagonism toward higher education has been especially intense over the last three months. In the days immediately after October 7, 2023, some students and faculty members on some campuses made awful statements excusing or endorsing Hamas’s brutal and indefensible terrorist attacks on Israeli civilians. The public outrage was understandable and intense.

In the turbulent weeks that followed, universities have been accused of tolerating or even promoting antisemitism. Demonstrations on some campuses have become disruptive or disorderly. Jewish students have reported feeling unsafe. Pro-Palestinian students and faculty have been doxxed for expressing views deemed to be antisemitic. The limits of free speech, and its relation to hate speech, once again became the subject of intense debate.

The campus climate at Princeton has been healthier than at many of our peers. That is a credit to faculty, students, and staff who have searched for ways to communicate civilly about sensitive issues, to support one another, and to comply fully with Princeton’s policies that facilitate free speech in ways consistent with the functioning of the University. I am grateful to all of you.

Many campuses have experienced more fraught confrontations, and a few university communities have had to deal with potentially lethal violence. A Cornell student threatened to kill Jews and “shoot up” the university’s kosher dining hall. Three Palestinian students from Brown, Haverford, and Trinity were shot and wounded on their way to dinner Thanksgiving weekend in Burlington, Vermont. Two of them were wearing keffiyehs, according to police.

In December, the House Committee on Education and the Workforce called the presidents of Harvard, MIT, and Penn to Washington for a hearing about antisemitism on their campuses. Near the end of more than four hours of testimony, the presidents gave technical answers to questions about free speech and calls for genocide that demanded clear statements of moral principle.

I respect the values and capability of all three presidents who testified, and I agree with New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg’s assessment that they walked into a trap — but walk into it they did.1 The damage has been significant not only for them personally, but also for the reputations of their institutions and for colleges and universities more broadly.

People are right to insist that colleges and universities stand firmly against antisemitism. Antisemitism is an ugly and vicious form of hatred that has produced horrific suffering and injustice throughout history. It is always unacceptable. So too are anti-Arab and Islamophobic hatred, which get less attention from the public or Congress even though they are as deplorable as antisemitism and also rising rapidly.

Some people, however, have seized upon public outrage about antisemitism as a stalking horse for other agendas, including, most notably, attacks upon the efforts that we and others make to ensure that colleges and universities are places where students, faculty, researchers, and staff from all backgrounds can thrive.

Some of these arguments are nakedly partisan jeremiads, but others come from centrist voices. A prominent example of the latter variety is a widely viewed six-minute video opinion piece by the respected CNN journalist Fareed Zakaria alleging that “American universities have been neglecting a core focus on excellence in order to pursue a variety of agendas — many of them clustered around diversity and inclusion.”2

These attacks are wrong. America’s leading universities are more dedicated to scholarly excellence today than at any previous point in their history, and our commitment to inclusivity is essential to that excellence.

Of course, scholars, students, journalists, and citizens can and, indeed, should raise questions about how best to pursue excellence and inclusivity. Disagreements are natural and essential to improving scholarly and civic communities.

In this crucial moment, however, when our colleges and universities are being wrongly and sometimes dishonestly attacked, those of us who care deeply about higher education must also transcend our differences. We must speak up for what we do and for our extraordinary institutions, which are so valuable to learning, to research, and to the future of our nation and the world.

Excellence

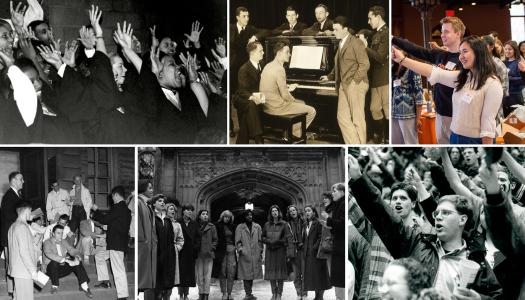

I have tremendous respect for the achievements of this University throughout its history and for the many generations who have passed through its gates. They have made distinctive contributions to the world, and they have pushed Princeton to become ever better. The resulting improvements have been spectacular.

Indeed, only dewy-eyed nostalgia, baleful ignorance, or an ideologically driven determination to erase history could justify a claim that leading American universities were more focused on excellence in the past than they are today. Exactly the opposite is true. America’s leading research universities have dismantled one barrier after another to become the genuine centers of excellence that they are today.

Princeton’s history is illustrative. In the early twentieth century, Old Nassau had a reputation as “the finest country club in America”3 — a place where privileged young men loafed rather than studied. When asked early in his Princeton presidency about how many students were at the University, Woodrow Wilson reportedly quipped, “about 10 percent.”4

A half-century later, Princeton was still boasting about its willingness to accept marginally qualified students. In 1958, Princeton’s Alumni Council published a booklet reassuring alumni who might be upset because the University was at last admitting significant numbers of applicants from public high schools.

The booklet insisted that Princeton would admit any alumni child likely to graduate. As evidence it proudly boasted that the sons of Princetonians were overrepresented in the bottom quartile of the class and among those who flunked out.5 Today, by contrast, the alumni children accepted at Princeton are every bit as good as the other students whom the University admits.

The Alumni Council’s brochure spoke about Princeton’s sons because, of course, the University did not admit women until 1969, thereby turning away roughly half the world’s excellence. That was one of many arbitrary distinctions that this University and others embraced at the expense of excellence.

Wilson, for example, opposed the admission of Black students. He infamously declared that “the whole temper and tradition of [Princeton] are such that no negro has ever applied for admission” and that it would be “altogether inadvisable for a colored man to enter Princeton.”6 Not until Robert Goheen’s presidency did the University make a concerted effort to attract and matriculate Black students.7

At Princeton and other Ivy League universities, antisemitic quotas persisted into the 1950s. Asian and Asian American students, who now form such an impressive part of the student body at Princeton and its peers, were virtually absent. Earlier this year, we dedicated the Ikeda Arch in honor of Kentaro Ikeda ’44, who (with his lifelong friend Richard Eu ’44) was one of only two Asian undergraduates in his Princeton class.8

Financial barriers also discouraged brilliant students from attending Princeton and its peers in decades past. Thanks to the strength of its endowment and with the enthusiastic support of its generous alumni, Princeton made trailblazing improvements to both undergraduate financial aid and graduate scholarships at the beginning of this century. Other institutions followed our example. Over the past two years, Princeton has announced another round of major improvements to undergraduate financial aid, graduate fellowships, and postdoctoral stipends that will open more doors for talented students and scholars from all socioeconomic backgrounds.

At Princeton and a very small number of peers, the improvements to undergraduate financial aid include full need-blind aid for international students. When I was an undergraduate in the early 1980s, international undergraduate students were comparatively rare in the Ivy League, and many hailed from well-to-do families that could afford to pay full tuition. Many more international undergraduates now study at Princeton and its peers and, at Princeton, the percentage of international students receiving need-based aid is higher than for domestic students.

The elimination of barriers to entry coincided with two other changes: an increased willingness of students to travel for an outstanding education and improved informational tools that colleges could use to assess the quality of students, and vice versa.9 The result, as documented by Stanford University economist Caroline Hoxby, is that student bodies at America’s best colleges and universities are significantly stronger academically today than they were in the 1980s or 1990s.10

Princeton’s internal data show striking changes consistent with Hoxby’s more general findings. Princeton’s undergraduate admission office has long assigned academic ratings to all applicants based on their scholarly accomplishments in high school, with 1 being the best and 5 being the worst. In the late 1980s, Academic 1s made up less than 10 percent of the University’s applicant pool and less than 20 percent of our matriculated class. Indeed, if you plucked a student at random from the Princeton University student body in 1990, the student was as likely to be an Academic 4 as an Academic 1 (but unlikely to be either: Academic 2s and 3s made up half the class).

In recent years, by contrast, Academic 1s have constituted roughly 30 percent of the applicant pool and about 50 percent of the matriculated class. Princeton’s academic excellence has increased substantially across every segment of its undergraduate population.

Standards have also risen on the faculty. Historian Nancy Weiss Malkiel reports that when Bill Bowen took office as Princeton’s president in 1972, “Princeton was clearly first or second in the country in departments like math or physics, [but] there were many others that were less distinguished. Bowen was determined to change that by ‘strengthening the faculty.’”11 Malkiel concludes that “there is no doubt that he succeeded admirably.”12

Emeritus professor R. Douglas Arnold has compiled a meticulous history of faculty hiring in the School of Public and International Affairs; it provides one quantitative measure for the trend that Malkiel describes. Arnold reports that “only 27 percent of the 15 external hires [in SPIA] in the 1960s were later elected to the [national] academies, compared with 73 percent in the 1980s and 100 percent in the 1990s.” (The national academies recognize the most distinguished and accomplished professors in their fields.) Arnold concludes that “in [its] first two decades, the School hired some faculty who became academic stars, but they were the exception. By the 1980s and 1990s, hiring academic stars was the norm.”13

This relentless quest for excellence has continued in Harold Shapiro’s presidency, Shirley Tilghman’s, and my own. Princeton has dramatically increased the quality and depth of its programs in American studies, African American studies, bioengineering, chemistry, the creative and performing arts, and neuroscience, to name only a few examples.

The trend continues. For example, the historic reconstruction of the School of Engineering and Applied Science, now in progress on Ivy Lane, will enhance the School’s ability to attract and retain outstanding faculty, graduate students, and undergraduates.

In short, the Princeton of today is better than that of yesterday, and the Princeton of tomorrow will be even better than the Princeton of today.

Inclusivity

Many people who disparage the excellence of America’s leading universities do so with a clear target: they aim to stoke animosity toward diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. More specifically, they insist that there is a choice to be made between resolutely seeking excellence and aggressively promoting inclusivity. That is wrong.

The excellence of America’s leading research universities, including Princeton, depends not only on attracting talented people from all backgrounds but also on ensuring that they can thrive on our campuses. We know that people face differing barriers to success, and we try to support groups and individuals in ways that meet their needs and allow their talents to develop.

To better understand those needs, we and other colleges and universities collect data about the student experience on our campuses. We ask undergraduates, for example, whether they would encourage a high school student resembling them to attend Princeton — in essence, would you make the same choice if you had it to do over again?

At Princeton (and, I suspect, at many if not all of its peers), these data show that Black, Latino, Indigenous, and LGBTQIA+ students report lower rates of satisfaction and belonging than their white and Asian, cisgender and heterosexual peers. Very few colleges release this information. Princeton publishes key data annually because we believe that we should be transparent about the challenges we face and the goals we set.

The data matter because gaps in satisfaction and belonging adversely affect academic performance, mental health, and other key elements of student flourishing. One major goal of this University, and of Princeton’s outstanding diversity and inclusion professionals, is to eliminate those gaps by improving the experience of underrepresented minorities and marginalized groups. We want all students and groups to have genuine opportunities to thrive at Princeton and in the world beyond.

In his CNN video essay, Zakaria accuses universities of caring about some groups rather than others. He declares that “it is understandable that Jewish groups would wonder, why do safe spaces, microaggressions, and hate speech not apply to us?”

I have little sympathy for the lingo of “safe spaces” and “microaggressions.” They strike me as the wrong way to describe the University’s inclusivity goals.

There is, however, a much more fundamental problem with Zakaria’s complaint: its premise is flatly false. Princeton and other universities do support the wellbeing of Jewish students in many ways, including through workshops on Jewish identity and antisemitism and through dynamic and attractive versions of what might — for those who like the terminology more than I do — be called “safe spaces.”

In 1993, Princeton opened its Center for Jewish Life in partnership with Hillel International. Princeton created CJL to give Jewish students “a home of their own at Princeton” where they could be “at the core” of the University and act as “hosts” not “guests.”14 In 2002, the Scharf Family Chabad House opened, with the stated aim of “creating a home away from home for Jewish students at Princeton, where all are welcome no matter background or affiliation.”15

The Center for Jewish Life and Chabad House are unique structures at Princeton. They respond to Judaism’s distinctive combination of religion, culture, and ethnicity, as well as the history of antisemitism at Princeton and its disturbing persistence in the world.

As I said earlier, Princeton endeavors to support each group and individual in a way suited to their distinctive needs. Beyond that, we want all students to feel that this entire campus is their home, that they are at the core of the University, and that (to borrow the language that President Bowen used to describe the Center for Jewish Life) they are at Princeton as hosts, not merely as guests.

That aspiration is at the heart of the outstanding work done by Princeton’s diversity, equity, and inclusion professionals. They seek to make Princeton a true home for students who are military veterans or first-generation college students; for students of all religions, ethnicities, races, socioeconomic backgrounds, nationalities, and gender and sexual identities; for students with disabilities; indeed, for students of every group and background.

That crucial work increasingly requires not only skill and commitment but also courage from our staff. For example, our nation is experiencing surges in homophobia and transphobia that threaten the LGBTQIA+ members of the Princeton community. As the staff of our Gender + Sexuality Resource Center sought to support our students in this difficult period, they had to endure vicious trolling from prominent hatemongers, people who pretend to oppose “cancel culture” even as they cynically practice an exceptionally ugly version of it.16

I am grateful to our team in the Gender + Sexuality Resource Center for persisting through this online abuse. I stand with them, and with everyone at Princeton who seeks to make this campus an inclusive home for all students, faculty, and staff.

Free Speech

Controversy over the war in the Middle East has rekindled arguments about the scope of free speech on campus. The tenor of that debate has shifted considerably. People who recently insisted that universities must protect the hateful bilge spewed by outside agitators such as Milo Yiannopoulos now demand that colleges should punish their own students for the language used in pro-Palestinian protests.

As we consider these new and disturbing demands for censorship, we should begin with basic principles.

Free speech and academic freedom are the lifeblood of any great university and any healthy democracy.

Princeton’s mission of teaching, research, and service depends upon giving the members of our community broad freedom to propound controversial ideas about science, humanity, justice, ethics, and every other subject, and to express those ideas forcefully and provocatively. Our mission depends upon a willingness to confront and respond to claims that may be heterodox, shocking, or offensive.

For that reason, Princeton’s policy on free expression provides students, faculty, and staff with “the broadest possible latitude to speak, write, listen, challenge, and learn.” Our policy, like the First Amendment, protects even speech regarded by “some or ... most members of the University community to be offensive, unwise, immoral, or wrong-headed.”17

These protections apply not only to the formal discourse of the seminar room but also to the tumult of the public square. At this University and in our nation, the impassioned voices of student demonstrators have played an essential role in drawing attention to issues that have been neglected and groups that have been marginalized.

We know, of course, that offensive and immoral speech — whether published in an article or chanted in a demonstration — can cause great pain. We protect it nonetheless for two reasons. 18

First, we believe that the free exchange of ideas is essential to the pursuit of truth.

Unpopular or even shocking arguments may ultimately prove meritorious. Ignaz Semmelweiss, the nineteenth-century doctor who first suggested that handwashing could prevent infection, was treated as a lunatic (literally: he was committed to an asylum and died after being beaten by guards).19 Albert Einstein scoffed at some foundational principles of quantum mechanics, saying that “God does not play dice.”20 Computer scientists for decades dismissed “neural nets,” the powerful algorithms that drive the current explosion in artificial intelligence, as an unpromising strategy or even a “dusty artifact” of an earlier era.21 The idea that anyone has the ethical and legal right to marry the partner of their choice, without regard to race or sex, was broadly considered scandalous until recent decades; it is now widely accepted.22

Even when arguments are wrong, listening to and rebutting them can deepen our understanding of our own positions, strengthen our capacity to defend them, and help to educate others.

Second, while we recognize that speech can sometimes cause real injury, great universities do not trust any official — their presidents included — to decide which ideas, opinions, or slogans should be suppressed and which should not. Censorship has a lousy track record.

Princeton has accordingly upheld free speech rights even in instances when doing so was unpopular with some or most people on campus. These include our determination that Princeton’s policies protected an allegedly racist student skit; the enunciation of a racial slur by faculty members in two different classes; and a student’s use of the same slur on a listserv.23

When the American Whig-Cliosophic Society invited the controversial law professor Amy Wax to speak at Princeton and then reneged, the University worked with Whig-Clio’s trustees to ensure that the student group rescheduled her talk.24 She eventually spoke without disruption, as have an enormous variety of other provocative lecturers invited to campus by faculty members or student groups.

Many commentators nevertheless suggest or assume that colleges routinely punish student speech. Zakaria’s video essay is again illustrative: he alleges that leading universities have “instituted speech codes” prohibiting students from saying “things that some groups might find offensive.”

That is untrue at Princeton and, to my knowledge, at our peer institutions. Punishing student speech is and should be exceedingly rare. The mere fact that speech is offensive is never grounds for discipline at Princeton; the speech must fall under one of the enumerated exceptions to our free expression policy, such as those permitting the University to restrict threats or harassment.

Disciplinary cases about speech almost always involve personally targeted speech, such as slurs written on someone’s door or hurled at specific individuals. That is harassment, which we rightly prohibit.

Critics of universities tend to slip casually between claims about punishment and teaching. For example, in an effort to prove his point about “speech codes,” Zakaria says that universities “advise students not to speak ... in ways that might cause offense to some minority groups.”

Universities do indeed advise students to treat one another with respect and to avoid unnecessary offense to anyone, including minority groups. For example, Amaney Jamal, Dean of the School of Public and International Affairs and one of the world’s leading experts on Palestinian politics, has advised against using provocative slogans such as “from the river to the sea” that might be construed as endorsing Hamas’s terroristic methods and aims.25

Advising students to avoid offensive speech, however, is very different from suppressing or punishing that speech. Advice is not a “speech code.” On the contrary, advice and counsel are part of education, which is the essence of what we and other universities do.

Universities must protect even offensive speech, but that does not mean we must remain silent in the face of it. On the contrary, we must speak up for our values if we are to make this campus a place where free speech flourishes and where all our students can feel that they are “hosts” not “guests.”

We must model and teach constructive forms of dialogue if we are to enable our students to build and inhabit a society more inclusive than the one that exists today.

We must also ensure that students are exposed to competing viewpoints, feel able to express thoughtful ideas and arguments even when they are unpopular, and know how to discuss controversial issues respectfully.

Promoting both free speech and inclusivity is a challenging task. There are, to be sure, times when we or others will make mistakes. When we do, we should strive to correct them and become better. Some critics instead seize on those examples as ammunition for an ideological assault.

Indeed, in the immediate aftermath of the congressional hearing on campus antisemitism, a bevy of articles — including at least four in the New York Times alone — referenced a single two-year-old lecture disinvitation by a department chair at MIT as evidence that universities have a double standard when it comes to free speech. Remarkably, not one of those four stories mentioned that MIT had responded to the incident by strengthening its free expression policy.26

Cries of censorship carry great weight, and critics may use them in an effort to smear universities even when we do the right thing.

In 2022, for example, Princeton dismissed a tenured professor for misconduct that included obstruction of the University’s investigation into his impermissible sexual relationship with a student.27 He and his backers claimed that he was fired because of his controversial contributions to campus political debate. Not so: his speech was irrelevant to his dismissal. He was treated neither better nor worse than other tenured faculty members whom Princeton fired after they obstructed investigations into prohibited affairs with students.

Unpopular or offensive speech may be protected, but it never excuses other, independent violations of university policy. Our responsibility is to stand strongly for all the University’s defining values, including its commitments to scholarly excellence, inclusivity, and free speech, and to do so even when circumstances are hard and criticism is fierce.

“At a Slight Angle to the World”

My predecessor William G. Bowen described research universities as existing “at a slight angle to the world.”28 A great university will inevitably generate ideas that agitate the society around it. It will challenge orthodoxies. It will call out gaps between our aspirations and our achievements. It is a place for radical ideas, ideas that can change the world.

American universities are engines of creativity, and their contributions have been essential to our nation’s prosperity, security, culture, and growth. They have for generations attracted talented people from around the globe. They have been, and remain, the envy of countries throughout the world.

Sustaining these extraordinary institutions requires a nation that is confident and strong.

Great benefit comes from allowing colleges and universities to operate “at a slight angle to the world,” but that divergence can feel irritating or threatening precisely because it is generative and potentially transformative.

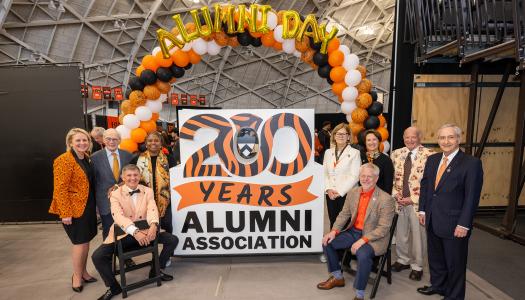

At Princeton, fortunately, the culture required to support a great university remains healthy and intact, both on our campus and beyond it. That is very much a tribute to the good work of faculty members, students, and staff who work diligently to build strong relationships across differences of background and viewpoint, as well as to the trustees and alumni who support the University in these turbulent times.

When I talk with Princetonians today, one of the most frequent questions I hear is, “what can I do to help the University?” Here is my answer: be an ambassador for Princeton and for higher education. Tell the story of how Princeton mattered in your life, about the excellence that you see, and about the shared and distinctive mission of colleges and universities in our republic.

We need to build on the strengths of our University. We must stand up more broadly for the excellence of America’s universities and for free expression. We need to explain and champion the radical idea that in college and in our society, people of all backgrounds and identities should feel themselves to be at home rather than present merely as “guests.” We must speak up for the value of what we do and the freedom that makes it possible.

I look forward to working with all of you to tell that story and pursue this University’s mission energetically and affirmatively in these troubled and turbulent times.

1 Michelle Goldberg, “At a Hearing on Israel, University Presidents Walked Into a Trap,” New York Times (December 7, 2023).

3 Jerome Karabel, The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton (Houghton Mifflin, 2005), 20.

4 Id. at 59.

5 The Alumni Council of Princeton University, “Answers to Your Questions About the Admission of Princeton Sons,” (June 1, 1958).

6 Arthur S. Link, ed., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson 15 (Princeton University Press, 1973), v. 15, p. 462, 550; v. 19, p. 557.

7 Eddie R. Cole, The Campus Color Line: College Presidents and the Struggle for Black Freedom (Princeton University Press, 2022).

8 https://www.princeton.edu/news/2023/09/19/princeton-names-campus-arch-kentaro-ikeda-44-universitys-sole-japanese-student; https://president.princeton.edu/blogs/strengthening-ties-asia

9 Caroline Hoxby, “The Changing Selectivity of American Colleges,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 23, no. 4 (2009): 95.

10 Id. at 98-99.

11 Nancy Weiss Malkiel, Changing the Game: William G. Bowen and the Challenges of American Higher Education (Princeton University Press, 2023), 95.

12 Id. at 117.

13 https://arnold.scholar.princeton.edu/document/571.

14 Malkiel, Changing the Game, at 181.

15 https://www.puchabad.com/mission-and-history

16 Lia Opperman, “Princeton Affirms Commitment to DEI After Information About Several Employees Shared,” Daily Princetonian (December 19, 2023).

17 https://odus.princeton.edu/protests/princetons-commitment-freedom-expression

18 https://president.princeton.edu/blogs/free-speech

19 See, e.g., Sherwin B. Nuland, The Doctors’ Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever, and the Strange Story of Ignac Semmelweiss (W. W. Norton, 2003).

20 Abraham Pais, Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein, 2nd ed. (Oxford University Press, 2005), 440-43.

21 Fei-Fei Li, The Worlds I See: Curiosity, Exploration, and Discovery at the Dawn of AI (Flatiron Books, 2023), 194.

22 See, e.g., Randall Kennedy, Interracial Intimacies: Sex, Marriage, Identity, and Adoption (Pantheon Books, 2003); Michael J. Klarman, From the Closet to the Altar: Courts, Backlash, and the Struggle for Same-Sex Marriage (Oxford University Press, 2012).

23 https://paw.princeton.edu/article/clash-values; https://paw.princeton.edu/article/classroom-clash-professors-words-hate-speech-course-stir-student-walkout-campus-controversy; https://paw.princeton.edu/article/students-outraged-after-university-clears-professor-who-said-n-word; https://www.dailyprincetonian.com/article/2020/08/student-racial-slur-social-media-free-speech-policy-princeton

24 https://www.princetonmagazine.com/whig-clio/

25 https://youtu.be/i7xJDK-rX9M?si=-6BjJcqIduq8hw_X. The meaning of the phrase is contested. Karoun Demirjian and Liam Stack, “In Congress and on Campuses, ‘From the River to the Sea’ Inflames Debate,” New York Times (November 9, 2023); Bryan Pietsch, “‘From the River to the Sea’: Why a Palestinian Rallying Cry Ignites Dispute,” Washington Post (November 14, 2023).

26 Bret Stephens, “Campus Antisemitism, Free Speech and Double Standards,” New York Times (December 8, 2023); Nicholas Confessore, “As Fury Erupts Over Campus Antisemitism, Conservatives Seize the Moment,” New York Times (December 10, 2023); John McWhorter, “Black Students are Being Trained to Think They Can’t Handle Discomfort,” New York Times (December 13, 2023); Vimal Patel, “The Fall of Penn’s President Brings Campus Free Speech to a Crossroads,” New York Times (December 14, 2023). President Kornbluth’s statement about MIT’s new free expression policy is here: https://news.mit.edu/2023/letter-mit-community-embracing-freedom-expression-0217.

27 https://paw.princeton.edu/article/trustees-fire-tenured-professor-citing-investigation-misconduct

28 William G. Bowen, “At a Slight Angle to the World” (Opening Exercises Address, 1985), as reprinted in William G. Bowen, Ever the Teacher (Princeton University Press, 1988), 5, 12. 11