David L. Evans *66 engineered a revolution in college admissions

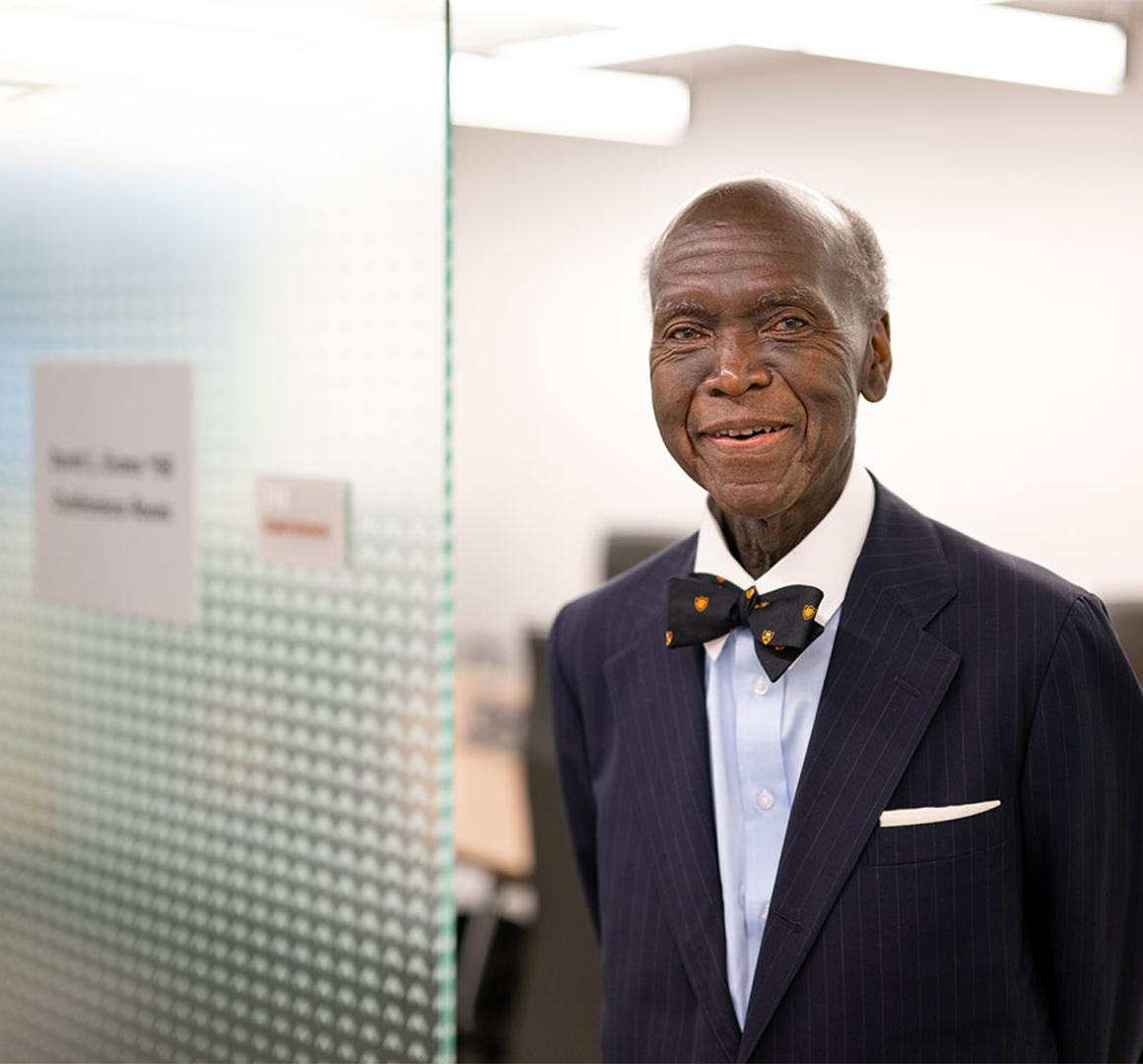

Standing outside the Admission conference room dedicated in his name, David L. Evans *66 briefly recounted the distances — in geographic miles and personal history — that brought him to that moment.

“I was working in Huntsville, Alabama, as an engineer on the Saturn Apollo project and I saw some of the students attending the newly integrated school who were doing very well, even though they were dealing with terrible experiences,” he said at the room’s dedication in June. “And I wrote to colleges [on their behalf], about what was there… My first two successful admits to the Ivies were to the Class of 1973 of Old Nassau.”

Considered a “legend” in college admission circles, according to Dean of Admission Karen Richardson ’93, Evans went on to spend 50 years as a Harvard University admissions officer championing diversity in higher education. In his five decades there, approximately 6,000 Black students were admitted to Harvard.

A winner of the prestigious Harvard Medal in 2020 for service to that university, Evans swapped his trademark Harvard tie for one emblazoned with Princeton shields to honor his graduate alma mater. After the ceremonial ribbon-cutting, he sat at the head of the room’s conference table to inaugurate its use with family and friends, including Richardson and President Christopher Eisgruber ’83.

Letter-writing campaigns

When integration of Huntsville public schools began, Evans went to the head guidance counselors of some of the high schools and volunteered to help African American students who had dreams of college. “I wrote to maybe 40 or 50 colleges in the country, including all the Ivy League,” he said.

Letter writing had been a strategy Evans employed successfully in his own life. After receiving admission to Princeton’s Graduate School to study electrical engineering in 1964, Evans wrote to several alumni associated with the Danforth Foundation and the New York Times for help with financial aid. Through those correspondences, he eventually heard from one of the Graduate School’s deans, who informed him that he hadn’t received financial aid because he hadn’t applied for it! The situation was rectified.

Why Princeton for graduate school? As an undergraduate at Tennessee State, Evans was impressed by a visiting electrical engineering professor from Vanderbilt University, who happened to be a Princeton alumnus. When Evans arrived on Princeton’s campus, he estimates there were a dozen African Americans in the graduate school and maybe a dozen admitted with the Class of 1968.

“The joke was, wherever we went, most of the time, we were not only a ‘s-o-u-l’ brothers, but the ‘s-o-l-e’ brothers,” Evans said.

In Huntsville, Evans’ letter writing helped local students attend Smith, Brandeis, Columbia, Stanford, Dartmouth, Morehouse, Amherst, and Chicago, in addition to Princeton and others. His efforts impressed the College Board and other universities. Chase Peterson, Harvard’s dean of admissions, invited Evans to take a two-year leave of absence from his job at IBM and join his team in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Evans demurred and recounted the exchange:

“I said, ‘but I’m an engineer by education.’”

Peterson replied, “I’m a medical doctor by education.”

Evans came back with, “I’m a Black guy from Arkansas.”

Peterson countered, “I’m what you would call a Mormon from Utah.’”

Convinced, Evans took a pay cut and moved to Cambridge in 1970. Two years stretched to 50. “I forgot to count,” he quipped.

A Pioneer

Evans was born to sharecropper parents in Arkansas who had six years of education between them. Both of his parents died by the time he was 17, but he and his six siblings all attended college and three earned advanced degrees. Education was recognized as a path to success, Evans said.

His career spanned a racially fraught time in U.S. history. From his vantage point today, he offers this advice to students: “Try to stay current on events going on, in our country and world, and on history over the last 60 or so years. Try to compare yourself as best you can with what your parents and your grandparents experienced to bring us to where we are. You will learn what history might expect given the opportunities that you have.”

The conference room dedication bookended six decades of affiliation with Princeton in a meaningful way. “I was taught that regardless of the height we attain, it is less meaningful without knowledge of the depth from which we ascended,” he wrote to Dean Richardson after the ceremony. “The worldview fashioned by that ‘climb’ influenced my voluntary — and improvised — guidance counselor efforts in Huntsville and a ‘two-year’ sabbatical, in 1970, to work in the Harvard College Admissions Office that became 50 years.”

His experiences also influenced the founding of the Association of Black Admission and Financial Aid Officers of the Ivy League and Sister Schools, which grew out of the realization that sharing information on how admission offices organized could help more students.

“You never think of yourself as being involved in pioneering things while involved in them,” Evans said. “Later you have something to compare them to."

Returning for the University’s third conference for Black alumni eight years ago, Evans commented on the contrast between 1964 and 2014: “This campus, like all the others — if it was a condiments table, there was salt and a very small shaker of black pepper. Today, there’s salt, pepper of many flavors, cinnamon, saffron, and fascinating combinations thereof.”