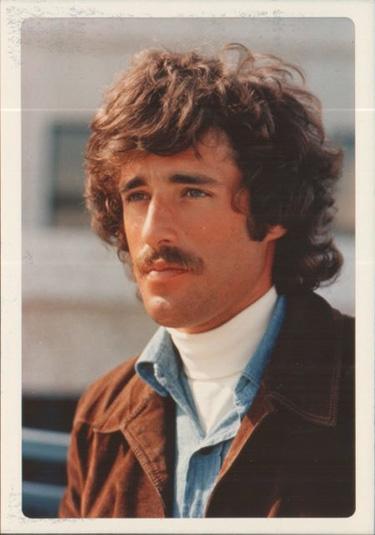

Joel Rosenman ’63: Life Lessons From Princeton to Woodstock and Back Again

Pools of roadside mud, miles of haphazardly parked cars, and thousands of midnight revelers made the route to Max Yasgur’s dairy farm nearly unpassable for Joel Rosenman ’63 and his motorcycle.

He could hear the music grow louder as he slalomed his bike through the gauntlet of obstacles. He was racing against time. If he didn’t deliver the two bank checks for $10,000 he had in his backpack to the stage, the Woodstock music festival could take a nasty turn.

The Who and the Grateful Dead had decided at the last minute that they would no longer accept Woodstock’s checks. They wanted cash or they weren’t going to play. Rosenman, the 26-year-old co-creator of the legendary 1969 event, had to scramble. He woke up his banker with a phone call and sent a helicopter to the man’s backyard, flying the pajamas-clad financier over the traffic jams and to the bank office a few miles away. Now, as the clock ticked, Rosenman revved his motorcycle and followed the music.

The closer he got, the more congested the route became. But once he reached the periphery of the vast field that had been transformed into a cultural epicenter of peace and music, he couldn’t help but pause to appreciate the beauty and the gravity of the moment.

“Janis Joplin was singing ‘Piece of My Heart,’ and she was brilliantly lit up by the spotlight,” Rosenman said. “And in my backpack, I was carrying the cashier’s checks that would keep the crowd from becoming very unhappy. Threading my way through the audience was difficult, but it was also exhilarating. I felt, briefly, like a hero.”

Everybody Get Together

No one in August 1969 knew what Woodstock would become — or that nearly half a million people would trek to Bethel, N.Y., for “Three Days of Peace and Music” that defined a generation. Rosenman and his partners — John Roberts, Michael Lang, and Artie Kornfeld — envisioned something like the Monterey Pop Festival, which drew about 28,000 people in 1967. “When we applied for our permits, the number that we put down was 50,000, because we figured that if we could get twice as many as they had at Monterey Pop, we’d be standouts in the festival world,” Rosenman said. “There was no way to anticipate that ten times that many were going to show up.”

No warning. No social media tracking. No advance helicopter shots of the mass pilgrimage up the New York State Thruway. “I woke up and looked out of my trailer window on Wednesday morning and there were already 30,000 people in the cow pasture where the stage was being built,” Rosenman said. “They had come early to get good seats. By the end of Friday, we were the second biggest city in New York state.”

For an event that is celebrated 50 years later as a glorious achievement, Woodstock never seemed comfortably far from disaster to Rosenman and Roberts. The two friends had built and run Media Sound, a state-of-the-art recording studio in Manhattan. But they had no experience organizing a music festival or booking bands. “None of the four of us had ever produced anything bigger than a birthday party,” Rosenman said. “Inconveniently, the managers and the agents for the bands knew we were novices. They refused to commit their bands to an event that might never take place. We solved that problem by throwing money at it; we paid the bands twice as much as their going rate.”

It was expensive but it’s what enabled Woodstock to deliver big names, like Creedence Clearwater Revival, Joan Baez, and Jimi Hendrix. Ironically, outside of his Evel Knievel race to the stage, Rosenman rarely witnessed any of the iconic performances. “There were very few moments when I could just sit back and enjoy,” Rosenman said. “John and I were just nose to the grindstone, on the phones at all times, tackling problems that were coming in at a rate that was faster than we could solve them.”

So there was the talent to deal with. Then there was the rain, with associated fears of mass electrocution. Then the threat of a crackdown from the governor and the National Guard. It was 1,001 things, nearly all of them related to the massive crowd — half a million kids stretched out in front of the stage, most of whom didn’t pay. “I’m sure they would gladly have paid,” Rosenman said, “but we hadn’t had time to erect fences and install ticket gates.”

“Lucky is the right word,” said Rosenman, when he reflected on how well the crowd behaved. “We were strained to the point of breaking, but it never broke. People had to make do with less and less and had to help out each other more and more. They found a way to include the adversity in the good time they were having. Everyone signed on to the instinct to take care of his neighbor. Everybody believed that they were all in this unique moment together.”

The Show Must Go On

Rosenman may have been a festival neophyte, but Woodstock and Media Sound were not his first musical ventures. As a student at Princeton in 1959, he co-founded the Footnotes a cappella group, which celebrates its own landmark anniversary this year. During his years in the group, they traveled extensively, performing in places like Detroit, Baltimore, and Puerto Rico.

“When you sing or perform, you bring energy to the stage and then you hope that that energy is communicated to the audience and bounced back to you — sometimes even greater than what you put out,” Rosenman said. “When I stood in front of an audience, I thought, ‘Wow, this is amazing.’ The feeling of the energy coming back is stunning and wonderful.”

It was a feeling he didn’t want to give up. Even after Rosenman graduated from Yale Law and took a job at a firm in New York, he continued to perform in Manhattan clubs as a singer. Legendary Columbia Records talent scout John Hammond was impressed and offered him a recording contract.

“I was about to jump at it, but he said, ‘Before you sign it, take it home and think about it. I usually offer this contract to people who have no alternatives. But you have four years at Princeton, three years at Yale. You have a lot of alternatives, and you may not like this kind of life,’” Rosenman said. “He was right. I went back to his office the next morning and turned it down.”

But he decided he wasn’t cut out for the office life either. That same day, Rosenman quit his job at the law firm. “I went back to my apartment having had two careers in the morning; by the afternoon, I was unemployed,” he said.

He connected with Roberts and they pitched a TV show about two naive venture capitalists who toss money at harebrained schemes. To generate ideas, they posted advertisements in The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times that read, “Young man with unlimited capital. Seeks interesting and legitimate proposals.” The nutty get-rich ideas poured in, but distractions like the festival relegated their sitcom to a shelf in the closet.

“I always had the confidence to do the next thing in life, and I think I got that from the way they teach you to handle success and failure at Princeton — to just keep on going forward,” Rosenman said.

Talkin' 'Bout the Next Generation

Today, Woodstock and music still hold important places in Rosenman’s life. He has spent a lot of 2019 participating in Woodstock-at-50 retrospective events, such as movie screenings and Q&As. (He appears in “Woodstock: Three Days That Defined a Generation” and “Creating Woodstock,” documentaries that have appeared at various film festivals and are available on Netflix and other platforms.)

These days he has teamed up with Marshall Brickman, the Oscar-winning screenwriter (“Annie Hall”) and Tony-nominated playwright (“Jersey Boys”), to collaborate on a musical based on his experience. “He downloaded my book, ‘Making Woodstock,’ from Amazon, read it, and phoned me,” Rosenman said. “He said he liked the book and thought we would write well together.”

They’ve been working on it for two years, and are currently in the fine-tuning stage. “We write together several times a week, sometimes every day.

It’s been a long, strange trip for Rosenman, from mowing lawns in Long Island as a kid, to performing at The Bitter End night club, to creating a music festival that shifted the culture, to an impromptu performance with fellow Footnotes alumni at his son’s recent wedding.

“I can trace the roots of this interview with you to way back — and way back is Princeton,” Rosenman said. “I think the most important thing I learned at Princeton was how to write. My profs at Princeton demanded good writing. If I managed to write something well, they would praise it and then tell me to make it better. It amuses me that there were times during my senior year at high school when I believed that I didn’t need to go to college at all. These days it’s the opposite — I’m beyond grateful for what I got from my Princeton education.”

As a member of the 1746 Society, for those who have included Princeton in their estate plans, and as a loyal contributor to Annual Giving, Rosenman is committed to extending that opportunity to future generations.

“The light bulb goes on a lot at Princeton. I give because I think it’s really important for future generations to have the same opportunities I had. The gift is just money. What it buys is priceless.”

Rock on.