John Mack ’00 is back: Meet the new leader of Princeton Athletics

The new athletic director sat down for an expansive Q&A to discuss his path back to Princeton.

Shortly after John Mack graduated from Princeton in 2000, he bumped into Gary Walters ’67, Princeton’s longtime athletic director, in the lobby of Jadwin Gymnasium. Mack, who was on campus to help Princeton’s track and field coaches run their summer camp, had moved back to his native Michigan and started a job with General Motors. Nevertheless, Walters asked him, “Have you ever thought about college athletics as a career?”

“Yeah,” said Mack, half-jokingly, “I want your job.”

The encounter led to Mack’s first job in intercollegiate athletics — as Princeton’s assistant director of intercollegiate programming — launching a career that included leadership positions at the Big Ten Conference and Northwestern University.

On Sept. 1, he returned to Jadwin Gymnasium, sat down in Walters’ old office and began his first day as the new Ford Family Director of Athletics, succeeding Mollie Marcoux Samaan ’91, who announced in May she was stepping down to become commissioner of the Ladies Professional Golf Association. “Most people don’t get their dream job,” Mack said. “This is the only job as an athletic director that I want — that I’ve ever wanted, really.”

Mack had been a star 200- and 400-meter sprinter at Princeton and a recipient of the William Winston Roper Trophy recipient as the top male senior student-athlete in 2000. On the track, he won a total of 10 Ivy League Heptagonal titles and helped Princeton to the indoor and outdoor championship each of his last three years.

After his first stint in the Princeton athletics department — during which he also served as assistant women’s track and field coach from 2002 to 2004 — Mack worked for the Big Ten as associate director of championships. Then he joined Northwestern as senior associate director of athletics for sales and marketing — while also earning his law degree from Northwestern in 2014.

Since then, he’s been a practicing attorney as well as the pastor at the Greater New Hope Missionary Baptist Church in New Haven, Michigan. “This job is the one thing that makes all the different things that I’ve done make sense,” Mack said, “combining both my previous experience in intercollegiate athletics, my time as an attorney, my time serving as a pastor and in organizational leadership. This makes all of that make sense.”

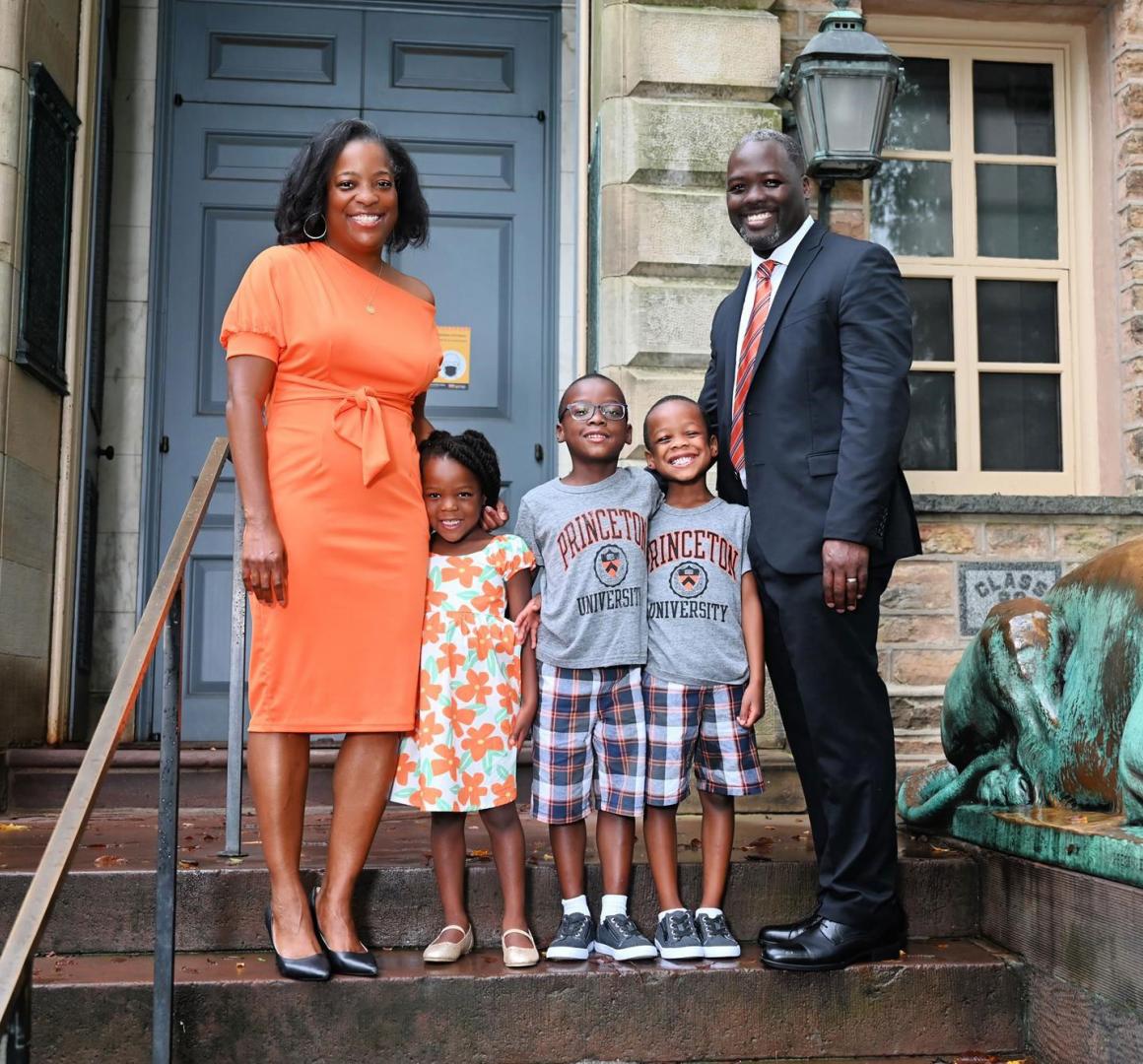

Mack and his wife, Alleda Mack ’99, have three children: Jacobi (6), Jabari (5), and Anaiah (4). All five are excited to be at Princeton. “When I worked here previously, as a single guy in his early 20s, I told people if I was in my 40s with a couple of kids, this would be the best place in the world to live and work,” said Mack, remembering the young children of coaches and administrators who made themselves at home in and around Jadwin. “But to be here now, two decades later, it’s almost indescribable how excited and thrilled I am to be back.”

In a Q&A, Mack chatted about his path to Princeton — and back again — and his hopes for the future.

You were a very successful athlete in high school. Was Princeton always on your radar?

No. I’d grown up an hour and a half from Ann Arbor, so I grew up a huge Michigan fan and planned to attend Michigan. But in August of 1995 — and I remember it like it was yesterday — I was standing in my living room, and my mother yelled down that there was a coach from Princeton on the phone. Coach Mike Brady was on the other line — this big, deep baritone voice — and he starts talking about Princeton, how I’d love the place and that I’d be a great fit. He was relentless in the recruiting process, so my parents and I came out here to kind of rule it out, really. I loved talking to Coach Brady, but basically, we came to visit Princeton just to tell him “No” in person.

But literally from the minute we set foot on campus, I fell in love. There’s just a magic to the place. Flying home, I said to my parents, “If I get in, that’s where I want to go to school.” And a few weeks later, when I watched the basketball team beat UCLA in the NCAA Tournament, I said, “God, this is the place for me.” And the rest is history. It’s been the best experience of my life. I met my wife here. Some of my best friends I met at Princeton, and just the way that the place has continued to show up in my life has been unbelievable.

The student-athlete experience at Princeton is kind of unique. What did you learn during your four years that helped shape your future?

For me, my experience was learning that Princeton is a safe place to struggle. Most everyone here is used to being the best student, the best athlete, the best at everything they’ve ever done. And for me, this was the first place where I had to struggle, where I wasn’t the best, where everything didn’t come naturally. You are literally thrown in with the best and the brightest from around the world, both in terms of the students and the professors and faculty. But everywhere I turned, people were there to offer support, to offer help. It was always a place that made me feel like I belonged.

One of the messages I want to leave our student-athletes is that not everyone’s going to be an academic All-American here. But what Princeton does, even though you might be struggling, is set you up for excellence for the rest of your life. I’ve heard Craig Robinson ’83 say how, when he left Princeton, he felt that he could compete with anyone in the world intellectually. And I felt the same way. When I went to law school, I was able to do really well because of the experience that I had at Princeton.

When you were an undergraduate, was there a moment or a mentor that made you think college athletics was something you might want to do as a career?

When I was a freshman, the equipment manager Hank Towns hired me to work sidelines at football games. And then Jerry Price hired me to work in the athletic communications office. For most student-athletes, you kind of have tunnel vision of your sport, your practice, your experience, but those jobs gave me a chance to see some of the other moving pieces that make athletics work. I’ve had the opportunity to do just about everything there is to be done in college athletics, but it started with getting a chance to do lots of different things as a student-athlete.

When you first joined the Princeton athletics department in 2000, you got to peek under the hood and see how the engine ran. Now it’s 2021. How do you think the responsibilities of a college athletic director have evolved in 20 years? Or is it pretty much the same model?

I think in the Ivy League, it’s the same model: You are a student first and foremost always, and the athletic experience is a part of your student experience as a whole. I think that’s why our model of “Education Through Athletics” rings so true: It really is an extension of your experience as a student. That has always been our model here in the Ivy League and at Princeton, and I think that will always be our model.

What has changed, both in the Ivy League and elsewhere, is that there’s much more attention now to the student-athlete as a whole — the job of trying to provide 360 degrees of resources for student-athletes. When you talk about mental health support and more well-rounded physical training, I think there’s so much more focus on that, and rightfully so.

One of the things that we’ve learned — looking at athletes like Simone Biles or Naomi Osaka — is that just because you’re excelling in competition doesn’t mean you don’t need support, that you don’t have struggles. And I think the attention to that globally has changed. At an institution like Princeton, we have the ability and the resources to provide that. Here, we talk about the team around the team: the dieticians, the mental-health specialists and all the people who help student-athletes and coaches. Again, that’s regardless of whether you’re a national champion or just somebody who is fighting for playing time.

I think that that’s one way that college athletics and being able to sit in this chair have really shifted over the last 20-plus years and is continuing to evolve.

You’re the sixth consecutive Princeton athletic director to have been an alumnus, dating back to 1941. What does that streak say to you about the Princeton culture and Princeton athletics?

I’m biased — this is the absolute best place to be a student-athlete in the entire country, bar none. We pursue excellence here on every front: as a student, as an athlete, if you’re in the orchestra, if you’re performing at McCarter Theatre — whatever it is. And I think the ability to come through that experience shapes you in a way where you just absorb the heartbeat of the place. When you talk about someone leading this athletics department, it helps to have someone who not just understands the University’s missions and values, but who really takes them to heart to be able to continue the legacy of what Princeton is about. I won’t say that you can’t do that without having been a student-athlete here, but I think it puts you light-years ahead on day one.

Several current student-athletes were part of the search committee for the new athletic director. What did you take away from your discussions with them?

For the second round of interviews, I met with Maddie Hamilton ’22 from our softball team and Niko Gjaja ’22, who’s on the men’s volleyball team. Their questions were really thoughtful, not just about their experience but about the student-athlete experience as a whole. I said this to someone yesterday: You almost forget how exceptional the students here are. Then you hear them speak, and it reminds you that this place is different. It reminded me why this job in particular is so special — because I get to work for and with the best students in the country.

We had our first-year student meeting last week, and a panel of current student-athletes answered questions about their experiences. The way that they articulated their experiences made me proud all over again just to be an alum of this place — because athletes are the University’s most visible students. There are people who associate with Princeton based solely on having seen the field hockey team, having seen the water polo team, having seen our student-athletes competing across the country. And to be reminded that this is the quality of students who are representing us just really speaks well of the job that our coaches and staff have done over the years.

When this position became available you had a big decision to make, because in a lot of ways, you were quite settled in Michigan working as an attorney and an ordained pastor. Was there part of you that felt as if the window for becoming an athletic director had closed?

Yes, I had kind of assumed that that window had closed, because athletic directors here tend to stay because it’s such a fantastic place. I think Mollie did a tremendous job and the department was in great hands. But when this opportunity came up, my wife said, “You’ve talked about this forever. If you don’t do this, you’re going to regret it for the rest of your life.” So I threw my hat in the ring.

I didn’t want to be an athletic director anywhere else. People over the years have asked, “Are you interested in this other job?” But this is the only job as an athletic director that I want, that I’ve ever wanted, really. And so, when it came open, it was an easy decision. It was a tough decision at the same time. It was a choice between staying home and coming home. But there’s never been a place anywhere in the world that has moved me like Princeton. It was just something I couldn’t turn down for myself, for my wife and for our kids.

You’re now in position to mold the next generation of Princeton coaches. Do you have a philosophy about what makes a great Princeton coach?

One of the things that Gary Walters always said is that the best coaches at Princeton are teachers who understand teaching not just their sport, but about the broader lessons of life. When you hear some people talk about their profession — whether it’s writing, whether it’s photography — you just get a sense of how much it means to them, that it’s not just a job, it’s part of who they are. I want people who have that passion, that their sport and coaching is really a part of who they are.

Princeton has rigorous academic standards that the University is not willing to, and shouldn’t, bend. You have to have coaches who believe in that mission and adopt it as their own. The best coaches are the ones who embrace that mission but are super competitive and want to excel and succeed in every area. I won’t be looking for cookie-cutter coaches. You have to have coaches who understand how to evolve themselves and their philosophies in order to maintain success because what worked 30 years ago may not work now. But again, finding coaches who understand and believe in the University’s core values is the starting point.

You return to Princeton Athletics at an exciting time. You can’t walk 100 yards without seeing some form of construction on or near the athletic facilities. What are you most excited about?

I’ve never seen this much activity going on at one time. My freshman year, they tore down Palmer Stadium, so the track and field team had to travel to local high schools for practice every day. It was a challenge. We didn’t get to have any home meets. I still remember when we finally had our first meet in Weaver Stadium — and Mr. Weaver was there — it felt like our team was home. So once all the cranes are gone and the construction’s done, I’m really excited to see the opportunities the new facilities present for our student-athletes, especially our soccer and softball teams, to see them get to have a chance to be in their own home athletically.

Not to get too inside-baseball, but you’ll be the first Princeton athletic director who has to deal with student-athletes who have the right to profit on their name, image and likeness. What have you already seen and what are you anticipating?

I hope we have student-athletes who get those opportunities. That means we’re bringing in high-quality student-athletes that people see the value in. I anticipate that we’ll have some students who’ll have that opportunity, and our job is to support them and make sure that they have as much information as we can provide.

I just want to make sure that they understand that they’re representing the University, they’re representing their families, and that anything that they enter into, they’re doing it with their eyes wide open as best they can.

I think nationally, it will take a few years before we have any real sense of what the name, image and likeness impact is going to be. Colleges will need to take a wait-and-see approach because there’s still so many unanswered questions when you look across the country and see some of those lucrative deals, especially surrounding football teams. There are already questions where the lines are. Again, we won’t know for some time.

Having the sports teams competing again really makes the campus come alive, and it’s wonderful to see them back in action after COVID cancelations.

I know our coaches and our student-athletes are so excited to get back on the field. Field hockey, volleyball and the soccer teams have started and the crowds have been tremendous. I think people have really been hungry to get back and support our teams. We’ve got Harvard and Yale at home for football, so I’m anticipating a tremendous response from our alumni for the football season and all of our teams throughout the year.