First-gen alumnus Kelton Chastulik ’21 paves path for others

Kelton Chastulik ’21 would set out from home nearly every week, carrying his camouflage-colored backpack. It was two and half miles to the Chambersburg library, but for a sixth grader, two and a half miles can be an epic afternoon adventure. Sometimes he’d bike, sometimes he’d walk, cutting though backyards to shorten his trek. Chambersburg is a rural Appalachian town in central Pennsylvania, what Chastulik calls a “last-name town” where people are known by the reputation of their kin. “There weren’t a lot of books in our house growing up, and you could only get one book at a time from my school library,” Chastulik said. “But the public library would let you check out 10 books.”

Inside the three-leveled library, he’d roam up and down the stacks, filling his backpack to the brim with books about all sorts of subjects. “Having a library card was so freeing as a kid,” he said. “I got to choose the books, and it was like a transaction I got to make for myself. I could finish a book a day, so I’d go back every week, and I would get 10 more.”

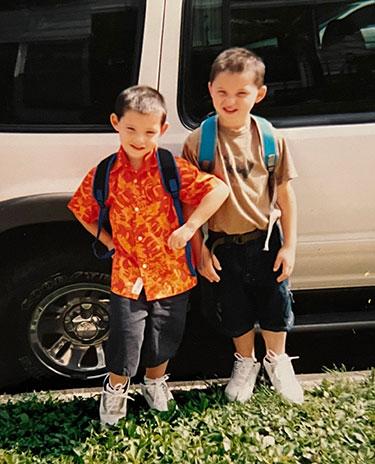

He read and he read and he read. His imagination blossomed, his academic performance soared, but his college goals remained modest — except he intended to play for the Pittsburgh Steelers when he grew up. His parents, who entered the workforce immediately after high school, were determined that Chastulik and his twin brother, Kyle, attend college. Kelton remembered laying out his plan when his parents asked: “I said I’m going to Shippensburg University,” Chastulik said. “Basically because it was a nearby college I knew about, and because my football coach had gone there.”

Chastulik never even heard of Princeton until his junior year of high school. It was the last of the colleges to recruit him for football and shot put, the track and field event at which he exceled after learning techniques from YouTube videos. He was hesitant to even visit because he wasn’t sure that his blue-collar background would be a good fit at Princeton. Ultimately, a generous financial aid package and the University’s mission of service won him over. “We didn’t have a lot of money, but my family has service running through its blood,” he said. “In lots of conversations with my parents and my brother, they urged me to take the time to soak up what Princeton is really like. And I took that to heart. Still, I definitely think it was scary.”

To help ease the transition, Chastulik was invited to participate in the Freshman Scholars Institute, a seven-week summer program for incoming first-generation and lower-income (FLi) Princeton students to take two classes, engage in co-curricular activities and acclimate to college life. For a teenager who had never flown on a plane before or traveled farther than North Carolina, FSI was eye-opening for Chastulik. His new friends and classmates were from other countries and different corners of the United States, and together, they learned about the University’s academic support resources, explored cities like Philadelphia and forged lasting bonds.

“I don't mean to say this in a cliché way, but FSI changed my life,” Chastulik said. “It really opened my eyes that there’s just so much more in the world than my small town in Pennsylvania. It was also life-changing because it instilled in me that I do belong here. It really kickstarted off a great Princeton experience.”

Chastulik threw himself into campus activities, participating in the Scholars Institute Fellows Program — which extended and deepened FSI’s mentoring and enrichment activities, and working as an ambassador with the (now-named) Emma Bloomberg Center for Access and Opportunity and the John H. Pace Jr. ’39 Center for Civic Engagement, creating programming for fellow FLi students “so that more people feel welcome and accepted” at Princeton.

Feeling a bond with the FLi community and realizing his heart was more attracted to its programs and activities, Chastulik decided not to play football so he could become more involved on campus. But he became an immediate standout on the track and field team, eventually becoming the Ivy League shot put champion.

During his sophomore year, he was selected for a NextGen Citizenship Fellowship, which entailed a Fall Break trip to Washington, D.C., where he met national leaders working on the future of citizenship and community engagement. “I got to meet these awesome public servants, and the energy there got me thinking, ‘What can I do?’” Chastulik said.

His mind immediately shifted to Chambersburg. His hometown and Franklin County are part of the country that struggled to keep up as manufacturing trends changed in recent decades, and the population of 18-35 year-olds in Franklin County had been declining. Political columnist David Brooks plucked the town from obscurity to illustrate the Red and Blue state divide that he documented for a much-ballyhooed story he wrote in 2001. “There’s such a gritty blue-collar community-care aspect of Chambersburg that I really love,” Chastulik said. “I can walk down the road, walk into a buddy’s house, sit down and have dinner.”

Inspired by an Icelandic holiday tradition of giving books as presents on Christmas Eve, Chastulik, his brother, Kyle, now a graduate student in music vocal performance at Temple University, and Madison Mellinger ’23 decided to organize a book drive for the Franklin County Homeless Shelter. With guidance and support from the Pace Center, they launched the drive with a modest goal: 200 free books for people in the shelter. The response was overwhelming: around 5,000 books were eventually donated to 18 different local organizations. “I came home from Princeton for winter break and, God bless my parents, the whole garage was full of books,” he said. “I counted books for three straight days.”

For Chastulik, the success was not just the quantity of books, but the community and thoughtfulness the project embodied. “I asked Princeton staff and faculty to donate their favorite book and to write a personal message,” he said. “One of my favorite things was being able to hand that special book to a student back home and that student realizing that there’s someone at Princeton University — someone from the No. 1 school in the U.S. News rankings — who thinks what we’re doing in Chambersburg is important.”

Chastulik had been contemplating a career in finance, but the success of the book drive and his partnerships with Chambersburg-area organizations helped clarify some of his goals. He wrote his senior thesis about the college decision-making process of rural students and challenged the conventional wisdom in Chambersburg that talented young people had to leave the area to find opportunity and success. Chastulik’s experience at Princeton made him think he could play a role in helping local students reverse that trend.

“When I had this idea about the book drive, every single staff member at the Pace Center sat down with me and gave me their time,” he said. “Princeton is a place where people want to see you do well. I think that’s a reason I decided to go back to Chambersburg, because I want to bring that same positive mindset back home: If you want to do something amazing, let’s figure out how to get you there.”

When Chastulik interviewed for a job with College Advising Corps during his senior year, he wasn’t shy about making one simple request. “I told the director, ‘I’m not accepting this job unless I go home to Chambersburg,” Chastulik said. “When I left for Princeton, there were people from home who thought I was going to fail — that Princeton wasn’t a place for people like us — but now I’m back because I don’t want to see anyone fail and I want to help people come back to Chambersburg and do great things.”

As a college and career advisor, Chastulik splits his time between Chambersburg Area Career Magnet School and his old high school, Chambersburg Area Senior High School, where he is an assistant coach for the football team. He gives presentations to classes and meets one-on-one with students to discuss their futures, sharing everything he knows about four-year colleges, community colleges, financial aid and scholarships, the military and workforce opportunities.

Last year, during COVID, he also co-founded Chambersburg to College, an online collaborative where students from his hometown share their college successes and failures in a collection of podcasts and first-person narratives. Younger students see that a path exists and that people just like them have successfully navigated it to achieve their dream.

“If students don’t have the necessary advising, especially if they’re first-generation, they’re likely to follow already-established pathways,” Chastulik said. “Teachers now say to me, ‘So-and-so wants to go to Princeton. Can you talk to them about it?’ I didn’t have that when I was in high school. So I hope that I can make an impact, helping students make bold choices when it comes to selecting a college.”

Chambersburg has changed since Chastulik left it to attend Princeton, and it continues to change. Buildings have been rehabilitated and economics have evolved. Downtown, there’s an artists’ co-op gallery, a breakfast café that sells crepes and Belgian waffles, and a Mediterranean restaurant. As someone who combines the perspectives of both an insider and an outsider, he knows for a fact it’s not the monolith that Brooks described in his 2001 story. “There’s literally a quote in David Brooks’ story that says you won’t find a mom driving a minivan with a Princeton sticker on the back,” Chastulik said. “I’m like, that’s my mom. My mom drives a minivan with a Princeton sticker on the back.”

He expects to see more of those types of stickers. His students emanate potential – one currently is a QuestBridge Scholar — and a major responsibility of his position is simply nudging them forward so that they dare to venture beyond what seemed impossible just yesterday. “I actually sit down with students and ask them, ‘What do you want to change in the world?’” Chastulik said. “I realize that for a 15-, 16-year old, that's a hard question to answer. But these kids, their minds explode when they think that big. That is what excites me the most about my job — seeing that moment, where it clicks and they think, ‘I can do this.’”