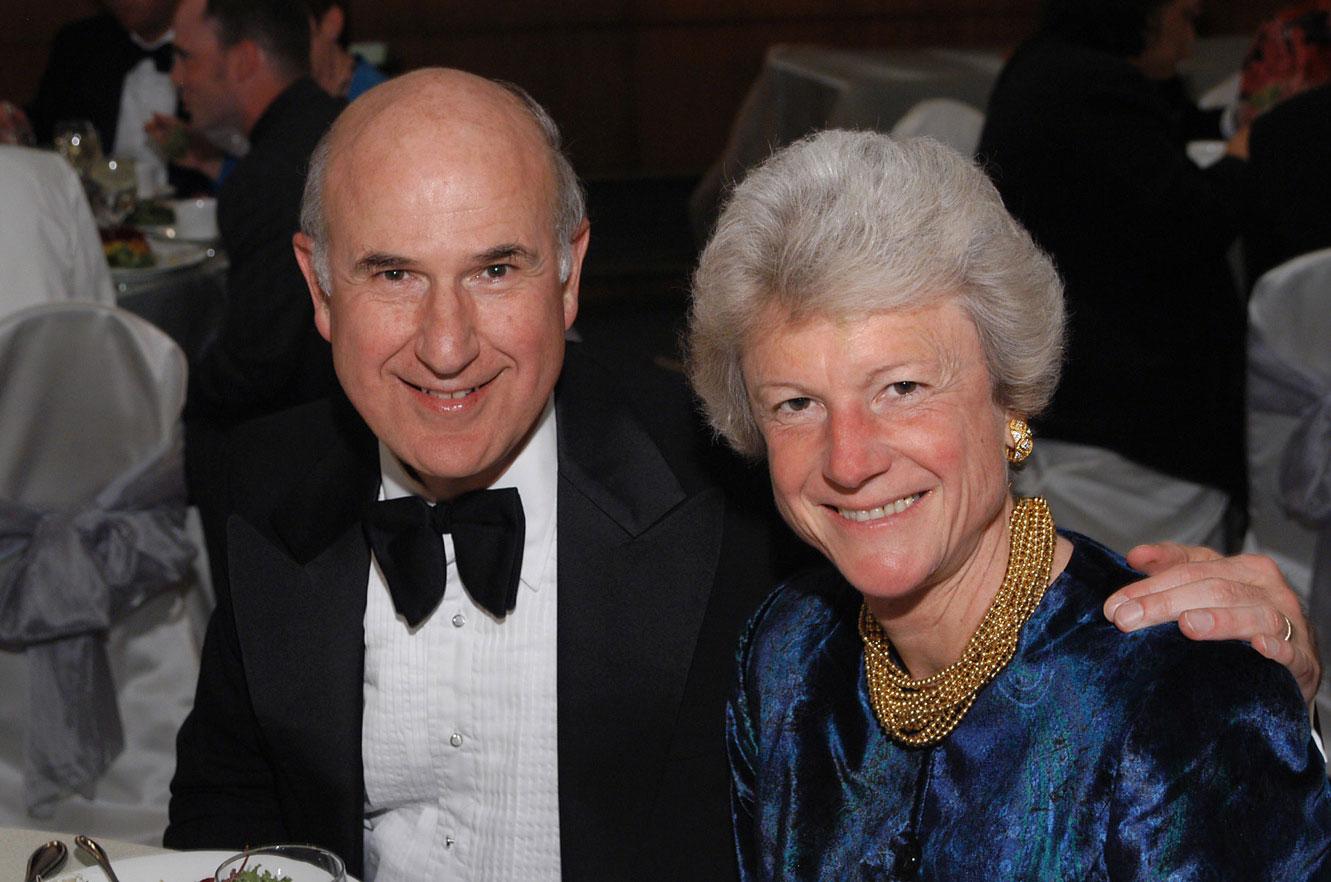

For Martha Darling *70 and Gilbert Omenn ’61, the City of Light illuminated a lifetime of service together

Photo by Kevin Birch

In May 1974, India put the world on edge when it became the sixth nation to detonate a nuclear device. Fears of further proliferation were heightened when France responded by announcing that it would sell its nuclear technology to India’s rival, Pakistan, to “level the playing field.” The Nixon Administration identified a White House Fellow assigned to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission to go brief the American ambassador in India, and then added Paris to the itinerary. The fellow was a physician-scientist from the University of Washington named Gilbert Omenn ’61.

In Paris, meanwhile, Martha Darling *70 was enjoying her life and work as a freelance consultant to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), where she analyzed women’s role in the economies of 10 of the group’s member countries. She loved Paris and identified with Hemingway’s description of the city as “A Moveable Feast.” After almost four years, she had accepted an offer from a research institute in Seattle to begin in fall of 1974. When an American friend in Paris called and invited her to dinner to meet his Seattle-based friend who was in town on his way to India, she accepted. The trio met at Roger La Grenouille, the iconic restaurant in Paris’ Rue des Grands-Augustins neighborhood renowned for attracting the likes of Picasso and Truffaut. That’s where Martha Darling first met Gil Omenn.

Omenn’s efforts in Paris and New Delhi bore fruit within a few weeks, as the French quietly withdrew from their nuclear agreement with Pakistan. “That was a pretty amazing result, buying the world 20 years, but I always say the highlight of that trip was meeting Martha Darling,” Omenn said. “Here we are today, coming up to 50 years together.”

“When people ask where we met, we always have a wonderful answer,” Darling said. “‘We met in Paris.’”

Since that chance meeting, Darling and Omenn have continued to lead lives of service and impact, guided by shared values that they say were reinforced at Princeton University. With a transformational gift, the largest in a long partnership with Princeton, the couple has established the Omenn-Darling Bioengineering Institute, which will promote new directions in research, education and innovation at the intersection of engineering and the life sciences.

The Path to Princeton

Omenn, the Harold T. Shapiro Distinguished University Professor at the University of Michigan, has had a notable career as a physician, biomedical and public health researcher, and academic leader. And Darling, who also later served as White House Fellow — working with Treasury Secretary W. Michael Blumenthal *53 *56 in the late 1970s — went on to senior leadership at Boeing and served in numerous national and state policy roles. Both arrived at Princeton as students from middle class backgrounds who believed there were no limits on what one could accomplish.

“It was a very different era,” Darling said. “The kids today can’t understand how innocent the time was. John Kennedy, the first president born in the 20th century, was elected in 1960, and the inspired words in his inaugural address talked about the torch being passed to a new generation. The Peace Corps was created, and there was a great positive feeling across the land. Our generation was set to have, relatively speaking, a much better time than our parents.”

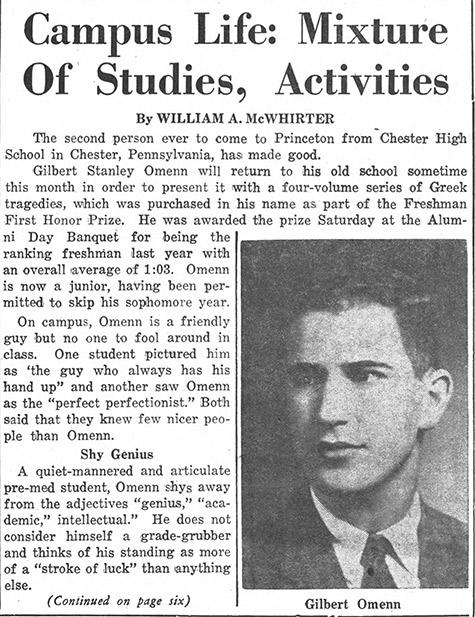

Omenn was the second student from Chester High School in southeast Pennsylvania ever to attend Princeton. He quickly reconsidered his plan to concentrate in mathematics when he realized he was the only Princeton student taking calculus who had not already had calculus in high school. “I was a standard smart kid, but a couple of my Brown Hall classmates were math whizzes already taking junior-level courses,” Omenn said. “I quickly was awakened to what might be required to be a math major at Princeton.”

Fortunately, Omenn was also interested in medicine, and the class that captured his attention was biology, taught by Professor Colin Pittendrigh, an evolutionary biologist and the coauthor of the class’s textbook, “Life.” “Actually, I was greatly stimulated by a wide variety of faculty,” Omenn said, “which led naturally to a career in medicine, public health and science policy.”

At the end of his first year at Princeton, Omenn received the Freshman First Honor Prize as the top-ranked student in his class and was permitted to skip his sophomore year. The following year, he was named salutatorian speaker for the Class of 1961 Commencement. His Latin address included a statement poking fun at Harvard’s controversial decision to change its diplomas from Latin to English that was quoted by the New York Times: “Although the men of Harvard have recently employed the English language on their diplomas (hiss here), we rejoice that you, the guardians of the Princeton tradition, still use Latin in ours (applaud most vehemently here).”

After a summer of research at the Brookhaven National Lab on Long Island, Omenn enrolled at Harvard Medical School.

Darling’s path to Princeton began nearly 2,500 miles away, growing up in Southern California. Her father had returned from World War II partially disabled, though he eventually made his way back into the workforce. Her mother, Lu Ann, who had graduated from Reed College, “found herself needing to go to work,” Darling said. “She took on a real burden as a working mother in the 1950s. She carved a path.”

Lu Ann later earned a doctorate and became a successful organizational consultant in health care administration. When she retired, she was the consultant in leadership and organizational development for Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles; she also authored a book on mentoring. Neither of her parents had finished fourth grade, but education was the key to everything for Lu Ann. “My brother and I were both brainwashed from an early age to think about small, private liberal arts colleges,” Darling said. “I went to Reed, and he went to Middlebury.”

Darling pursued American studies at Reed and became active in student government, becoming student body president. She also was involved with the National Student Association (NSA), a confederation of college and university student governments dedicated to equality and activism during the turbulent 1960s; a number of her NSA colleagues were on their way to Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School, now known as the School of Public and International Affairs. But when Darling initially applied to Princeton as a Reed senior in 1966, she wasn’t even invited to interview.

“The word I got was they weren’t taking women,” Darling said. “Princeton was then engaged in a two-year ‘experiment’ with one woman — Heather Ruth *67 — to see if she could survive the Woodrow Wilson School. Heather knocked it out of the park, and Princeton decided that for the next fall, they would admit women to the Woodrow Wilson School.”

In the meantime, Darling worked for Robert Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign. When she applied to the Woodrow Wilson School a second time, she was interviewed by Professor of International Affairs Richard Ullman in Washington, D.C., then working at the Pentagon. She was accepted and joined a small cohort of women at the Woodrow Wilson School in the fall of 1968.

“There was a group of five women the year before I came and then five more in my class,” Darling said. “Dick Ullman was a fabulous member of the faculty, and Uwe Reinhardt was such a charismatic lecturer. By the time I finished in 1970, it was the spring of Kent State and Cambodia, a devastating time in our nation’s experience. As a consequence, fewer graduates went on to government agencies and more to the Ford Foundation and developmental economics.”

In the midterm elections of 1970, Darling worked for a coalition called the Movement for a New Congress, recruiting students to campaigns around the country that led to Democratic gains in the House of Representatives and Senate. At the end of that year, she packed her bags and headed to Paris, where she would work as a freelance consultant for the next four years.

The Power of Giving Back

Omenn and Darling have been a formidable duo since their dinner encounter at Roger La Grenouille. In 1977, Omenn took leave from the University of Washington to return to Washington, D.C., as associate director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and then of the Office of Management and Budget for President Jimmy Carter. He was soon joined in the capital by Darling, who began her stint as a White House Fellow.

Since then, Omenn has been an academic and healthcare leader at the University of Washington — as director of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program, professor of medicine/medical genetics, and dean of public health — and then at the University of Michigan, as the first CEO of the UM Health System, and, since 2005, founding director of the University of Michigan’s Center for Computational Medicine & Bioinformatics. He chaired the global Human Proteome Project of the Human Proteome Organization, which is relevant to understanding advances in bioengineering, and served on the board of the biotech company Amgen.

After her White House fellowship, Darling became a senior legislative assistant for newly elected New Jersey Senator Bill Bradley ’65 in 1979. Soon after, the couple moved back to Seattle in 1982. Darling became a vice president of Seafirst Bank, Washington State’s largest bank, and later joined Boeing, serving as a senior manager in a variety of program management and public policy roles until they relocated to Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1997. Through it all, she also emerged as an influential conservationist, serving as a member of the 2016 National Wildlife Federation’s president’s leadership council and receiving the Federation’s National Conservation Achievement Award.

While their careers and their family have thrived, the couple has prioritized giving back to the educational institutions that have been meaningful to them. Darling is a longtime member of the board of trustees at Reed College, where she championed student life initiatives, established the Lu Ann Williams Darling ’42 Scholarship, created the Munk-Darling Lectures to bring distinguished speakers to campus, and enhanced funding for the dean of students. At the University of Washington, the couple led the establishment of the Arno G. Motulsky Endowed Chair in Medical Genetics and then the Gilbert S. Omenn Endowed Chair in Biostatistics and the Robert W. Day Endowed Professorship in Public Health Sciences, and made a major gift to support the 50th anniversary of its school of public health. At the University of Michigan, they support the Medical School, the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy and the University Musical Society. They serve on multiple non-profits, including the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, the Salzburg Global Seminar, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, the Center for Public Integrity, the Ann Arbor Symphony Orchestra and the Hastings Center for bioethics.

Their bonds to Princeton have deepened with time, and the University’s combination of strengths in engineering and policy match the couple’s own passions and professional experiences. As bioengineering has emerged as a cutting-edge discipline at Princeton with enormous global potential, Omenn and Darling have been generous advocates. Prior to their gift to name the Omenn-Darling Bioengineering Institute, they contributed gifts to create the Gilbert S. Omenn Lectures in Science, Technology and Public Policy, the Gilbert S. Omenn ’61 and Martha A. Darling *70 endowment for the Scholars in the Nation’s Service Initiative, and the Gilbert S. Omenn ’61, M.D., Ph.D., and Martha A. Darling *70 Fund for Grand Challenges in Bioengineering. Omenn also led a pre-pandemic review of the Lewis-Sigler Institute of Integrative Genomics, which is a partner in the Bioengineering Initiative.

“The more that is learned in this field, the more we realize we have yet to understand, a common experience,” Omenn said. “This is an exciting area, where new technologies, basic biology, and chemistry, physics, mathematics and computational sciences all need to be brought together.”

“Pairing biology and engineering together is very intriguing to us, especially because of Gil’s professional contributions in the fields of computational medicine and bioinformatics,” Darling said. “In addition, Princeton is uniquely positioned to highlight in-depth exploration of the ethical and policy implications of this rapidly evolving field.”

The Omenn-Darling Bioengineering Institute will turbocharge Princeton’s groundbreaking bioengineering research and teaching led by a team of core faculty members. “We believe in investing in the best possible people you can,” Omenn said. “We need people with brilliance, determination and purpose in all fields. Princeton provides that. Plus, Princeton represents a deep, meaningful relationship for each of us. This gift is significant because it is from us together — Martha and me — to Princeton.”

As Hemingway wrote, “There is never any ending to Paris.” For Darling and Omenn — and for Princeton — that is a great and wonderful truth.