The Year of the Tiger: ‘We have all these people that came before us, and we carry that in who we are’

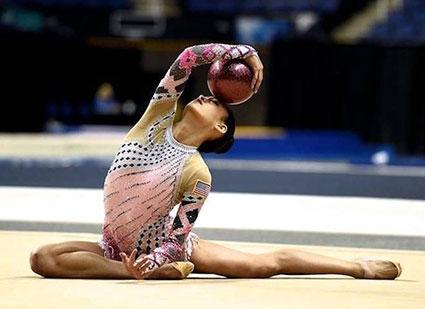

Photo courtesy of Serena Lu ’20

The Year of the Tiger that launched with this Lunar New Year is a moment of pride and reflection for Princeton’s vibrant Asian and Asian American community. Throughout the year, we are elevating the voices of faculty, staff, students, alumni and researchers in a series of thoughtful interviews exploring questions of identity, pride, hope, the lived experience of anti-Asian racism, and meaningful steps that allies can take.

We continue the series with Serena Lu ’20, who is now working as a paralegal with the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office in the Major Economic Crimes Bureau through a Princeton AlumniCorps Project 55 fellowship.

Lu is also an actor and dancer. She recently returned to competitive rhythmic gymnastics — she trained in hopes of competing at the Olympics while at Princeton but had retired her sophomore year. She attended the in-person Class of 2020 Commencement May 18 with her parents.

How do you self-identify?

I am Chinese American. My parents are from China, my mother from the north in an area called Harbin, my father from the south, I’m not sure where, which he’ll be upset to hear. They both went to Peking University and moved here about 30 years ago. My sister and I were born here and grew up in Blaine, Minnesota.

When I think about identity, my cultural identity is not the first thing that comes up. I felt I had to create other identities that allowed people to develop a framework of me outside of what I looked like: classical pianist, competitive rhythmic gymnast, athlete. These things established legitimacy. I experienced a tremendous loss of identity and deep grief when I retired from rhythmic gymnastics in 2018.

I refused to speak Chinese growing up, even though my parents speak Chinese at home. I had felt embarrassed that my parents had an accent because the kids in school were mean. I remember in third grade we were doing a verbal spelling exercise and I was spelling out this word. My dad pronounces the letter H as “etch” instead of “aitch.” I pronounced it “etch” and everyone started laughing. Our desks had tops that lifted for you to put your stuff in — I refused to go outside for recess. I just put my head in my desk.

My parents would pack my lunch for school and it’d be dumplings or something and kids would be like, “Ew, what is that?” I wanted more than anything to have a cafeteria school lunch, even though I loved what my parents cooked. I would go to school and think I needed to be as least Asian as possible.

Part of my parents’ identity for us was discipline — a lot of hard work, humility and focus. These are essential skills that I still rely on. My parents are very silent people and won’t talk about their sacrifices, but I know. I think they wanted my sister and me to grow up understanding what it’s like to work hard and dedicate ourselves to something.

We moved to New York in 2010 so my sister and I could pursue gymnastics training. Shortly after, we both made the National Team. I really self-identified as a national team athlete for the U.S. I was extremely proud of it, not only because it is a very difficult thing to do, but also because I never wanted anything more than to compete knowing I represented America. I never once thought, “I’m a Chinese American from the U.S.” I was just like, “I’m American. I’m representing this country.”

What makes you proud to be an Asian American?

It’s sometimes very hard to be proud because, honestly, I am ashamed of how much I tried to distance myself from that identity. I’m trying to work my way towards being comfortable identifying in that way.

Before I can feel proud, I think discussion needs to happen between myself and my parents, my sister and my friends. Everyone’s so silent about the fear we feel right now as Asian Americans. With my parents, we don’t talk about a lot of things because it’s not really the thing that we do. We need to heal as a part of the greater community, to reconcile with everything that’s happening and just be able to talk about it.

We are more comfortable showing how we care than talking about what’s happening. For example, I know my parents are scared for me in this climate of anti-Asian violence. My dad doesn’t let me take the subway at night. He drives me to and from the gym every day, six days a week, which is so out of his way. He lives in Staten Island and I work in Manhattan and my gym is in Brooklyn. I worry about my parents the same way because it’s so scary to know that anything could happen, it’s so random. We need to start talking about our fear.

What can allies and others do to counter Asian-American racism?

I’m at that age where I spend most of my time with my friends. I think it’s as simple — and it’s also not as simple — as listening. I would say, just listen to the fears and concerns that maybe your Asian American friends have around certain topics. Understand that it’s hard for them to voice those things and really try to hear them when they do.

A lot of my Asian American friends don’t feel like they have people they can talk to about these issues or don’t feel they’re actually being heard when they do. Recently, I had a conversation with some of my friends about fears of riding the subway and walking around at night in Manhattan. It is really terrifying. The initial step is listening to and checking in on your friends who are afraid. A lot of us didn’t grow up in environments where you can be comfortable just saying you’re afraid. I always feel like I’m taking away from someone’s time if I do that, or someone’s going to think that I’m making this all about me. Just be there as a listener and try to understand. Before anything can be done, we all have to reach that understanding.

Wanting to express a concern for your Asian American friends, people you care about, goes a long way. It’s not prying. It shows that you care and you want to know what it feels like. Also, keep an open mind about the things that you learn.

And understand this: Not all Asians are the same. We all go through different things. Even with my Chinese American friends, a lot of our families are different. Go past, “I love to eat this food. So therefore, I understand what it’s like.” Go past the fact that you may enjoy certain parts of the culture — music, movies, shows. Going past that surface-level distinction is really important. I’m glad that Asian American art and media are coming to the forefront but going past that is where the real understanding begins.

Another thing I think is really helpful is reading books and listening to podcasts by Asians about their experience. I think these are very beautiful resources. I am continuing to discover new AAPI artists to support.

Some books I’d recommend are “All You Can Ever Know” by Nicole Chung, “An Inconvenient Minority” by Kenny Xu, “Days of Distraction” by Alexandra Chang, “Minor Feelings” by Cathy Park Hong, “Sigh, Gone” by Phuc Tran and “The Loneliest Americans” by Jay Caspian Kang.

“Asian Enough,” “Dear Asian Americans” and “Self Evident: Asian American Stories” are three strong podcasts.

Are there examples from what you’re involved in to counter Asian American racism that empower you?

For me, the biggest thing is my involvement in the arts, being in performance spaces where people didn’t want you to be in historically.

I was recently in a student film by someone at NYU film school. It’s a story about the meaning of family. It’s a personal story but universal, told through the lens of two characters who are Asian American. The story is what’s at the forefront — not the fact that the characters are Asian American, although there are elements in the film that highlight the fact that they grew up in that culture. Those are the stories that I hope to see become more commonplace.

I’m also a member of the new Movement Headquarters, which is striving to build a company of dancers that resembles what New York looks like. I think that’s an important sentiment.

Returning to competitive rhythmic gymnastics has been a journey of finding ways of expression related to my Asian American identity. Before I retired, I never really thought about what I could say with my routines. Now I am working with Anthony Chen ’20, a friend I made in Triple 8, the East Asian American student dance ensemble at Princeton. He helped me with the vision for my ribbon routine to be Asian-art-oriented and helped me put together the soundtrack, a mix of music from the 2002 martial arts film “Hero.”

My routine is in three parts as an homage to “Hero,” a tale of three famous assassins and how the protagonist overcomes each one. Each part highlights a different kind of movement style, which I learned through researching Chinese dance and martial arts. It’s nice to have that intentionality and show people for the first time that this is who I am. Maybe I wasn’t so proud of that before, but now I am.

My acting teacher always instills in his students that we’re like vessels to our past. He says it’s very important for us to know where we came from and understand that we have all these people that came before us and we carry that in who we are.

—————

This interview was published first on the University website. Read previous conversations with Yibin Kang, the Warner-Lambert/Parke-Davis Professor of Molecular Biology; Stephen Kim, associate director of the Princeton University Art Museum; and Yi-Ching Ong, director of Princeton’s Service Focus program.