With Africa World Initiative, Chika Okeke-Agulu helms an innovative hub connecting Princeton with Africa’s most creative minds

Watch the Venture Forward video

On Chika Okeke-Agulu’s credenza, leaning against the wall of his office in Princeton’s Green Hall, are two powerful images: the cover of a vintage magazine and a photo that graces the cover of one of his recent books. It might be too easy, though, for a visitor to overlook them. After all, the art history professor’s office is brimming with conversation starters: original artwork, an oversized beaded fly whisk, Igbo sculptures, art history books, monographs and novels.

Stacked on the desk are fresh copies of the Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art, which Okeke-Agulu began co-editing more than 30 years ago. ARTnews, the oldest and most widely circulated art magazine in the world, has called it “massively influential.”

Seated at his desk on a quiet afternoon as the campus settled into a holiday break, the world-renowned scholar in African and African diaspora art history had just accepted a gift: an orange-and-black-flowered bucket hat, which he gamely donned, replacing the similar sartorial statement on his head. “I’m the chief of bucket hats,” he said with a grin.

In 2008, Okeke-Agulu brought his many literal and figurative hats, as well as a treasure trove of bold ideas, to Princeton. As the University’s first historian of African art, his arrival on campus signaled a shift.

With his belief that “the status quo is almost never enough,” he saw opportunities for change. When he was offered the role of director of the Program in African Studies in 2021, Okeke-Agulu thought about “what [the program] does, what it could do and what it could be.” While he had ambitious goals for bolstering the program, which has a history of excellence in the study of Africa through traditional disciplinary approaches of the humanities and social sciences, he also began talking with administrators about engaging Princeton “more meaningfully” with Africa, recognizing that Africa is not simply an academic subject but a continent rich in resources that will play an increasingly pivotal role in world affairs. By 2050, more than one in four people on the planet will be African, according to a recent forecast by the United Nations.

Okeke-Agulu envisioned creating something that in its initial stage would be independent from and complementary to the African Studies program: Something transdepartmental. Sweeping. Focused on the future.

Now, as director of Princeton’s Africa World Initiative (AWI), Okeke-Agulu helms a one-of-a-kind hub that aims to connect and engage the University’s research and teaching mission with the continent’s most creative thinkers. AWI is a platform for the University’s engagement with Africa and its stakeholders through the arts and humanities — and also across research partnerships in science, technology and innovation, entrepreneurship and public policy.

What brought the art history professor to this global mission? Those two images on the credenza, significant touchpoints to his story, hold some clues.

Dreamer to doer

Above the headline “Starving Children of Biafra War,” the haunted eyes of two children fix on the photographer’s lens. The black-and-white cover of Life magazine, July 12, 1968, is a gut-wrenching preview to the tale of savagery within its pages.

Born in Umuahia, Nigeria, Okeke-Agulu’s first years were precarious, amid a civil war that ripped the country apart from 1967 to 1970. Assessments of civilian deaths vary, but the Red Cross estimates 1 million children in the secessionist state of Biafra died of malnutrition and starvation, while only half that number survived.

Okeke-Agulu survived. And dreamed. As he grew up, he formed ideas about his future: He might become a cosmologist, or a Catholic priest. He studied the sciences in high school. He enrolled in seminary for a while. But then his heart, unexpectedly, pulled him to art.

Studying art at a university was a venturous choice. Okeke-Agulu had no formal art training. To prepare, he taught himself to paint using how-to books from the local market in Umuahia. “I did not know anyone who attended a university,” Okeke-Agulu said. “I had no idea what universities looked like or what people did there.”

He took an entrance exam for the University of Nigeria (UNN) Nsukka. It was the only one of the federal universities that didn’t require a high school diploma in art for admission — but he did need to submit a portfolio. On the advice of a friend of a friend, he roped together a collection of asbestos boards, the only surfaces he could access that were flat and large. In August 1985, he brought his portfolio to the Nsukka art department for review. The chair of the department informed him he had the highest score on the entrance exam of any applicant. The portfolio went unexamined. He was in.

Okeke-Agulu majored in sculpture. In 1990, he graduated as university valedictorian and was awarded a scholarship for graduate study at UNN Nsukka, which led to an MFA in painting. He began to emerge as a major artist, becoming the youngest of 15 members of the Aka Circle of Exhibiting Artists, founded in 1985 by El Anatsui, his former sculpture teacher, and Obiora Udechukwu, who had taught him painting. (An exhibition of the Aka Circle’s work was held in Lagos in November of 2024; the gallery described the Circle as “a pioneering force in Nigeria’s contemporary art scene … known for their radical studio experiments challenging Western art orthodoxies.”)

During this time, in addition to making art, Okeke-Agulu curated exhibitions, wrote art criticism and taught advanced drawing and sculpture at his alma mater.

In 1996, his days in Nigeria came to an end. At the height of a military dictatorship’s power, the national teachers union went on strike. The government insisted the UNN Nsukka faculty return to work and sign an oath pledging good behavior. Okeke-Agulu and 12 others refused. The eight resistors the government could find were arrested and charged with sedition and arson, which carried a death sentence.

Okeke-Agulu set his sights on the United States. He enrolled at the University of South Florida, where he received an M.A. in art history, and then earned a Ph.D from Emory University.

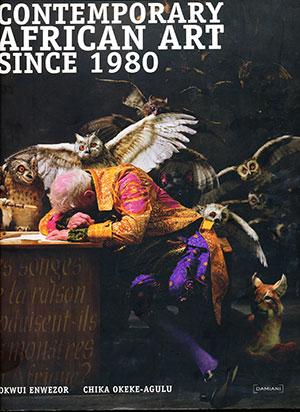

Throughout these years, he was also engaged in a broader cause: to change the field of African art history. In 1994, he had been contacted by Okwui Enwezor, a Nigerian poet and curator living in New York City who had the idea of launching a new magazine, the Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art, to showcase new artists whose work was neglected by existing art journals.

“The field of African art was the so-called traditional African art,” Okeke-Agulu said. “Although modern and contemporary African artists had been practicing since the beginning of the 20th century, few paid attention to their work. If you went to a gallery or museum to propose an exhibition of one or several African contemporary artists, they’d ask you, ‘Where can we read about these artists?’

“Very clearly, we, Nka’s editors, understood the connection between knowledge production and the fate of art and artists,” he said. “If you don’t produce the knowledge yourself — because no one else is going to do it for you — then the artists will continue to languish on the art world’s roadside.”

Nka was the first to consistently publish academic articles about numerous African, African American and African diaspora artists whose careers would blossom over the decades as the journal, and its founding editors, became increasingly acknowledged. One barometer of the recognition of contemporary African art on the global stage is its representation at Italy’s Venice Biennale, which Okeke-Agulu describes in the November 2024 issue of Nka as “the art world’s equivalent of the Olympics.” Only four African nations participated in 2011; at 2024’s 60th Biennale, for which Okeke-Agulu served on the international jury, there were 12.

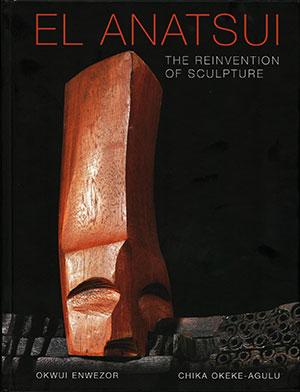

Some contemporary African artists now stand at the forefront of the art world. The second image on the credenza is a testament to Nka’s role in this sea change. Nka was the first academic journal to write about Ghanaian artist El Anatsui, Okeke-Agulu’s former teacher. The image is a striking detail of “Al Haji,” a 1990 wood sculpture by Anatsui that was used as the cover of “El Anatsui: The Reinvention of Sculpture,” a 2022 monograph co-authored by Okeke-Agulu and Enwezor. The piece features metamorphic, shape-shifting wood blocks with chainsaw and flame-burn marks.

Anatsui is now one of the world’s most celebrated contemporary artists, with works in the collections of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, London’s British Museum and Tate Modern, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. In 2023, he made Time’s list of the “100 Most Influential People” on the planet.

Today, with Africa World Initiative, Okeke-Agulu is applying the same question that fueled his efforts through Nka to help change the field of African art: “How do you tap into what already exists in order to build something that does not exist but is urgently needed?”

Future-forward with AWI

Chika Okeke-Agulu, in a red bucket hat, is interviewing Nigerian author and activist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on the stage of a packed Richardson Auditorium. They banter over who has the better story of a personal connection to Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, best known for “Things Fall Apart.” (Okeke-Agulu wins; watch it on YouTube.)

The tone turns serious when Okeke-Agulu asks Adichie how she writes “in this moment we live in.”

“I exist in a perpetual state of rage,” she says, speaking of her role not as novelist but as a Nigerian citizen. “I do not want to stop existing in that state of rage because … I have to believe there is hope for Nigeria.” Referencing a recent Nigerian election, she says, “We have a generation of young people who are increasingly disillusioned. I am enraged, but also, I am not letting go of hope.”

“I am not letting go of hope either,” replies Okeke-Agulu.

The event, in October 2023, was the first in the Africa World Lectures series, a flagship program of AWI that brings African luminaries to campus to share their ideas and discuss current realities and visions for the future of Africa. Another AWI flagship series is the Africa Impact Lectures, which invites significant figures whose work positively impacts their societies. Martin Fayulu, a politician from the Democratic Republic of the Congo who advocates for a new kind of democratic spirit on the continent, was the inaugural lecturer in September 2024. Ambassador Tete António, the Angolan foreign minister and council chair of the Southern African Development Community, will give the second lecture on April 17.

Just three years after the launch of AWI, the initiative’s programs, partnerships and projects encompass a range of research, policy and entrepreneurship. “It’s something that I cannot say exists anywhere else among our peer institutions,” said Okeke-Agulu. “This is why I’m so grateful to Nassau Hall for saying, ‘This is unusual, but we’re willing to see what you can do.’ There’s a lot of leap-of-faith in this.”

One project includes regular meetings of the Fusion and the Global South working group that Okeke-Agulu initiated with colleagues at Princeton Plasma Physics Lab. “There’s not a single country from the Global South that’s been involved in ongoing negotiations about fusion energy even though some of the resources that will power this are coming from there,” said Okeke-Agulu. AWI is also working with the leadership of the University of Botswana to plan net-zero studies for African countries by the influential Net-Zero America group of researchers at Princeton’s Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment.

The African Languages and Artificial Intelligence project aims to connect Africa with innovation in AI. While Africa boasts more than 2,000 languages, Okeke-Agulu said they are “abysmally absent in the ecosystem” of natural language processing, large language models and AI research. The current goal, using Princeton’s resources and talent in the field, is to create a high-quality dataset for 12 African languages.

AWI also hosts a continental African Innovation Council and plans a digital African Archives Project. The initiative sponsors two postdoctoral fellows within the Program in African Studies and hosts visiting scholars from African public and private sector institutions. Another idea includes establishing a studio and writer’s residency for East Africans at the Mpala Research Centre in Kenya.

A marquee program will be the Achebe Colloquium on Africa, established in 2009 at Brown University by the famous Nigerian novelist and poet during his lifetime to explore topical, complex issues affecting the continent. In 2023, Princeton partnered with the Christie and Chinua Achebe Foundation to host a Chinua Achebe Symposium and 10th Anniversary Memorial Celebration. Beginning in 2026, Princeton will host the Colloquium.

At the helm of AWI, Okeke-Agulu, who was named the Robert Schirmer Professor of Art and Archaeology and African American Studies in 2023, is both philosophical and driven by urgency. AWI is not about his own legacy, he said, but about doing work that has immediate and long-term impacts for Princeton and Africa.

“How do you account for your presence in any given space and place?” Okeke-Agulu said. “Being in a place like Princeton, it’s hard to give the excuse that the means of doing things are not there. The question becomes, What did you do with what you have or what you are given?”

The urgency is personal.

The crucible of war

“The Zulu occupied this space within the European imagination, and that impacted how we think and talk about art of southern Africa.”

In a classroom in Green Hall, Okeke-Agulu, wearing a blue checkerboard bucket hat, tells students in his “Introduction to African Art” class that many sculptural objects were mistakenly labeled as Zulu when imperialist European nations colonized southern Africa and pilfered its art for their own museums in the late 19th and early 20th century. Europeans equated the Zulu’s military prowess in the region with civilization and culture, Okeke Agulu explains. They incorrectly deemed other indigenous groups, such as the Tsonga, incapable of making figurative sculptures and depicted them as simple craftsmen.

Resetting views on African art is a focal point of Okeke-Agulu’s career. His current work includes curation — on tap is a major exhibition of El Anatsui’s print works at the Philadelphia Art Museum in 2026 — and serving on advisory boards for institutions across the globe, including the new Museum of West African Art (MOWAA) in Benin City, Nigeria, on the site of the ancient Kingdom of Benin, celebrated for its artists and artwork.

Okeke-Agulu is a leading voice in the call for the restitution to Nigeria of the Benin bronzes, including thousands of figurines, tusks, plaques and masks. The objects, notably not all “bronzes,” were looted by British soldiers from the kingdom in 1897 and are held in museum collections worldwide. While the calls for repatriation began with African independence in the mid-20th century, progress has only come in the last decade. In his letter from the editor in the November 2022 issue of Nka, Okeke-Agulu wrote: [R]epatriation and restitution of African cultural heritage has somehow become a key talking point for Europe’s culture warriors and nationals, who are bent on preserving at all cost the continent’s colonial heritage. These forces, I expect, will put up a serious, messy, but ultimately winless fight. And we, too, have to stay the course.”

These endeavors are but some of the impressive figurative hats he wears.

His primary hat, he said, remains that of artist. “Wherever I go, I look for artists. I still practice as an artist, and so I typically find myself more with artists and writers than art historians.”

His artist’s heart was forged in the crucible of war, his spirit of hope continually triumphing over the tragedies of his homeland. His past propels him forward to forge new partnerships and paint new connections that will help Africa realize its great potential in the arts, sciences and technology.

Those two credenza images, signifying his past and present, tell a tale of resilience and success, but also declare a determination to keep going, to keep effecting change.

“I’m very aware of how short life is,” Okeke-Agulu said. “It’s partly out of being born in a state of precarity … I got my first sandals in primary four to go to school, and so all of that experience is so crucial to what I do. I’m always working with a sense of urgency.

“I’m not leaving anything for tomorrow.”