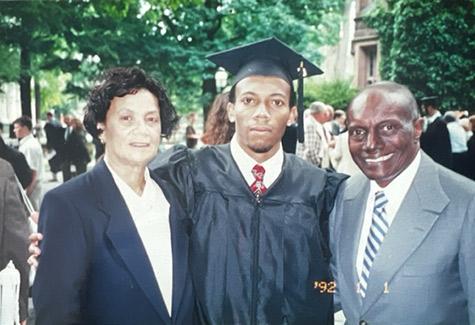

For David Foster ’01, establishing a scholarship is a ‘triple win’

Photo by Gabrielle Woodland

When David Foster rolls up his sleeves at work, he often finds himself sitting across the table from billionaires. As deputy general counsel of the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA), Foster is one of the attorneys representing more than 450 players in the union’s negotiations with National Basketball Association (NBA) owners. The stakes are high and conversations can turn heated, but the ultimate goal is a fair deal for both sides so that the league can continue flourishing.

“I think in business, I put the word ‘fair’ in quotation marks because that really depends on which side you’re on,” said Foster, who joined the NBPA in 2015. “The other side can credibly disagree with what I perceive as fair, right? You need evidence.”

In April, Foster was part of the team that brokered a new collective bargaining agreement between the players and owners for the next seven NBA seasons. The union projects that NBA players will earn more than $50 billion collectively over the course of the new seven-year deal.

“The No. 1 thing is to have your position grounded in the facts and to truly understand what the other side wants,” Foster said. “Stripping away the peripheral things — the extra things that always become part of the ask — opens the door to change things and get some of the things you both want.”

Foster has been making his case and winning arguments long before he joined the NBPA. A Fordham University Law School graduate, he worked for five years in the Queens County (N.Y.) district attorney’s office and another six years as an assistant United States attorney in Newark, New Jersey.

Joining the NBPA required some adjustments to his skills and strategies. “It isn’t until you actually leave that role [as a prosecutor] that you appreciate how much leverage you have in those negotiations,” Foster said. “By the time you get to the negotiating table with a defendant, you’re already confident you have everything you need to win. You’re naturally inclined to be more aggressive.”

“In my job with the NBPA, negotiations are much more equal,” he added. “If anything, I would argue management inherently has an advantage. I had to refine a lot of my negotiating strategies and recognize that I wasn’t playing with a lead. Oftentimes, I am playing from behind. But that’s life. You’re always making adjustments. You can’t use the same strategy forever.”

Making Adjustments

Foster’s first big negotiation, arguably the most important of his career, occurred while he was still a Princeton undergraduate. The judge and jury in that case was his father, Leroy, who had made sacrifices to send Foster from Barbados to live with Foster’s older sister in Philadelphia during high school so that he could attend an Ivy League institution and become a doctor.

“My father was very big on education,” Foster said. “The idea of going to college and ‘finding yourself’ does not exist for people with Caribbean parents: You’re going to be a lawyer or a doctor.”

Leroy Foster, as David Foster describes him, was a self-made man who never attended college. He was an ingenious entrepreneur who ran multiple businesses and eventually became a successful thoroughbred racehorse trainer and owner. “His life story was amazing — what he did with so little,” Foster said. “And he was always so much more confident in me than I was myself. I remember when I got into Princeton, he was like, ‘You should be there.’ Hearing that helped give me confidence. If my father said I should be there, I should be there.”

Foster received a need-based scholarship from Princeton, but his parents — Leroy and David’s mother, Claudine — also took out loans for him to attend. To them, it was an investment in his future medical career. But halfway through his junior year, while taking physics, he received an email from then-Assistant Dean of the College Marcia Cantarella that sparked several conversations about his post-Princeton plans.

“I told her, ‘I have to go to medical school — my parents said so,’” Foster said. “She said, ‘I’m sure you can do it, but it’s very difficult to make it through medical school unless you really love it.’ She really got me thinking, and because of her, I went home during winter break and told my father I didn’t want to go to medical school — but I am interested in going to law school.”

Foster made a convincing argument — a promising sign for the future attorney — and his parents endorsed his pivot to law school.

Princeton helped provide direction for Foster’s success in other ways as well. As a hurdler on the Tiger track and field teams, he learned the importance of preparation and dedication. “Athletics gives you an opportunity to try your hardest and fail — and have to try again,” Foster said. “You practice for weeks and weeks for one race, and if it doesn’t work out as you hoped, you do it again, practicing for weeks and weeks for the next race. That preparation process has been helpful to me in everything I do throughout life.”

Off the track, Foster found belonging in Princeton’s chapter of the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity. “Some of my fraternity brothers remain my best friends in the entire world; we all joined the fraternity 24 years ago, and they’re still the people I speak to more than anybody else,” Foster said. “I made Princeton my home through them, the teachers and my teammates on the track team.”

Since graduating, Foster has gained a deeper appreciation for the Princeton alumni experience available at every stage of life. “There are all these different professional organizations and various affinity groups that you can join, and being involved has been so beneficial to me,” Foster said. “Across race, age and other demographics, there is a genuine excitement when Princetonians meet each other. There are very few things in life like being a Princeton alum.”

A Guiding Light

Foster has supported the University though Annual Giving, with a perfect record of giving every year. More recently, he began to think of additional ways to do more for the next generation of Princeton students. In 2022, he began a conversation with classmates and Princeton friends about new ways to support the University. “I know lots of alumni like me who feel passionate about Princeton and want to help but don’t feel like there’s an avenue to do so,” Foster said.

He sent a group email to announce his plan to establish an endowed scholarship in his father’s name and invited his friends to consider doing something similar. Leading the enterprise was a natural assignment; for him, every day includes game-planning and communication, equal parts listening and explaining. “Sometimes you just need a spark to get it going,” Foster said. “I told them about my commitment and belief that the University really wanted to hear from us. This was an opportunity that this group of friends previously had discussed, about being present as alumni. They immediately responded.”

Two of his Princeton friends — Emanuel Slater ’99 and Reginald Jackson Jr. ’02 — established their own separate scholarship endowment funds modeled on the Leroy A. Foster P01 Scholarship Fund. For Foster, his scholarship is remarkable for the legacy of the man for whom it’s named. Leroy Foster passed away in 2005, while David Foster was in law school, but he remains a daily inspiration.

“He’s still my guiding light,” Foster said. “Everything I do, I think, ‘Am I making him proud?’ The concept of him having children who could walk into an institution like Princeton seemed pretty far-fetched, but he had the vision. This scholarship is an opportunity for me to honor him and show my friends that we have a lot to contribute to the University. This is a way to help others, to help Princeton and to make my father’s name live on. It’s a triple win.”