Making audacious bets on opportunity: David MacMillan becomes a catalyst for change

The train ride every morning from New Stevenston sometimes felt like a cruel reminder that teenage David MacMillan didn’t belong at the University of Glasgow. New Stevenston was an industrial working-class Scottish village in the shadow of Ravenscraig steelworks, one of the largest mills in Europe. Nearly every man of working age in New Stevenston punched the clock there or at the nearby coal mine. Some mornings, it felt impossible to wipe off all the red dust the mill sprinkled on every square inch of the village before MacMillan reached the imposing turrets of academia in Glasgow.

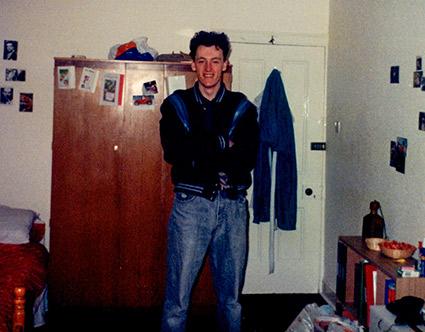

Attending a university in the city was a culture shock. MacMillan’s father had left school at age 14 and was a foreman at Ravenscraig; his mother assisted elderly village residents with their cleaning, cooking and household chores. “Most of the students who went to uni came from higher-class families,” MacMillan said. “They had money, they had their apartments, they could do all this fun stuff. Meanwhile, I’m taking the train in and out every day because I can’t afford to even really be there.”

MacMillan felt the financial implications in every decision, like, “Do I have enough money to have a lunch today?” Everything was a compromise, a negotiation to make ends meet; even his textbooks. His organic chemistry class recommended a glossy new textbook, but it was too expensive for him. MacMillan settled for a cheaper, older textbook and hoped for the best.

MacMillan was only on the commuter train because of his older brother, Iain, who bucked convention and went to the University of Strathclyde to study physics. His parents didn’t know anyone who had gone to college; they initially thought Iain was being “lazy,” trying to postpone real work. But when their father compared his own paycheck to Iain’s first wages as a university graduate, he decided, then and there, that young David would follow in his brother’s footsteps.

Now, as MacMillan sat on the train for an hour each morning, riddled with doubts, he pored through his bargain textbook and prayed that organic chemistry hadn’t changed too much since its publication. To his surprise, MacMillan discovered that the cheaper textbook may as well have been written personally for him. “I remember sitting on the train every day, reading this book — and it all just clicked in a way that other subjects had not clicked before,” MacMillan said. “Years later, I read that more expensive textbook, and it would not have worked for me. But that older textbook was written in the way that I think about things. It just made sense. Through it, I didn’t find organic chemistry; organic chemistry found me.”

GETTING THE CALL

On the morning of Oct. 6, 2021, MacMillan received a phone call that would change his life. Actually, he received several phone calls. The first few he ignored since it was before 6 a.m. He finally responded to a message from fellow chemist Benjamin List in Germany, who informed MacMillan that the two of them had been awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry. Suspecting a prank from his mischievous Princeton colleagues, MacMillan bet List $1,000 that it wasn’t true, hung up the phone and went back to sleep. It wasn’t until he logged on to his computer to check the day’s news that he fully believed: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences had awarded him and List the Nobel Prize.

“I open up the New York Times website and there’s my face!” MacMillan said. “That has got to be one of the most unbelievably surreal moments of my entire existence. I went back upstairs and woke my wife to tell her, ‘I just won the Nobel Prize!’ It was just completely bizarre but fantastic at the same time.”

MacMillan and List were recognized for developing asymmetric organocatalysis, an environmentally friendlier and inexpensive method to build molecules that drive chemical reactions. Previously, the process of accelerating a chemical reaction was driven by metals or enzymes, but those forms of catalysis could be expensive, toxic and unstable. Using small organic molecules, organocatalysis was simpler and safer, with greater scalability and less chemical waste. In the years since the two chemists developed the process — simultaneously but independently — the technology has transformed the pharmaceuticals industry and the manufacturing of everyday products like clothing, shampoo and carpet fibers.

At the time of MacMillan’s breakthrough in 2000, he was conducting research at the University of California, Berkeley, following doctoral and postdoctoral research at the University of California, Irvine, and Harvard. By any criteria, he was already an accomplished chemist, but nothing had come easily. After graduating from Glasgow in 1991, he had contacted 19 American universities with the hopes of continuing his studies in the United States. Only one, UC Irvine, responded. When they offered MacMillan a position, his father could hardly believe the generous stipend that came with it. He made MacMillan call the university to confirm it.

“The woman at Irvine’s international office clearly could not understand a word I was saying,” said MacMillan, whose brogue has softened since he was 21 years old. “Finally, she interrupted me and said, ‘I speak many languages: Can you try speaking in your native tongue?’ I was like, ‘This is all I’ve got.’ But it was a moment where I wondered if going to America would work. Was anyone going to understand me?”

MacMillan found when he arrived in California that people understood him just fine, and he immediately fell in love with the Golden State. In the summer of 2000, MacMillan joined the chemistry department at Caltech, considered one of the preeminent departments in the world.

THE QUESTION OF COOL

For six years at Caltech, MacMillan learned from the best and taught some of the brightest students. But he was looking for a fresh challenge when Princeton came calling. At the time, the University was looking to bolster its chemistry department by investing in faculty and facilities. Princeton was growing in ways that intrigued him.

“You become a professor at Caltech, and it’s like inheriting your dad’s Ferrari,” said MacMillan. “You didn’t buy it; you were given it. But coming to Princeton was a chance to join an amazing team of people and build our own Ferrari. There are not many places that have the resources, the drive, and the culture to do that, but Princeton did. This became a really exciting opportunity: to build a group, to build new programs, to be part of building a new department. I feel like I showed up here just at the right moment, and I have a tremendous amount of affection for those people who gave me this chance.”

Since arriving at Princeton in 2006, MacMillan became director of the Merck Center for Catalysis, chaired the chemistry department, helped launch the Princeton Catalysis Initiative, and was appointed the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of Chemistry. He also built a prolific research group that has pushed the science of catalysis far beyond the discovery that eventually earned him the Nobel.

MacMillan encourages chemists who join the MacMillan Group, as they’re deciding how they’re going to approach their research, to consider the very amorphous question: What is cool?

“You’ve got to have this inbuilt sense of what you think is cool, because if no one else thinks what you’re doing has interest — even though it could be an amazing discovery — it will be lost in history because no one else cares,” MacMillan said. “One of the things I really work on with the folks in my lab is creatively thinking about, ‘What does cool look like?’ If you can imagine new things that exist tomorrow in science that would really impact everyone, what does that look like? What would that be? And you start from there.”

MacMillan half-jokes that in his role, he sometimes feels like the editor-in-chief of a newspaper during a pitch meeting. “They’re bringing me stories all the time, and I’m simply going, ‘No… No… Yes, that’s great… No.’ We chase the most promising stories and sometimes they work out, sometimes they don’t.”

One of those stories that worked out was photoredox catalysis, the idea of using visible light to perform single-electron transfers. The MacMillan Group’s breakthroughs opened up new possibilities for research and the development of synthetic materials.

“We wanted to do chemistry with light, so we had to invent all these contraptions to do it,” MacMillan said. “People were sort of dead against it because it changed the way chemists were conducting experiments. But over time, we showed that the things you could do with it were so empowering. Now, every pharmaceutical company in the world uses it every day, because it’s changed the way we think about how to make molecules. Photoredox is one of the biggest areas in chemistry now.”

A CATALYST FOR CHANGE

The year since he woke to the Nobel news has been a whirlwind for MacMillan. He’s become a seasoned pro at television and radio interviews and perfected his smile for the inevitable selfie requests he fields at chemistry conferences. In June, he received a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II. “People from where I grew up just don’t typically end up being knighted,” he said when the honor was announced.

In its totality, the year has made MacMillan especially grateful to all the people who helped him along the way, beginning with his parents and the teachers in New Stevenston who enabled him to get on that first train to Glasgow in 1987. Recognizing that everything that followed — California, Princeton, the Nobel Prize — was because of the opportunities they provided, MacMillan and his wife, Jiin Kim MacMillan, established a foundation to help other first-generation, low-income students.

Named for MacMillan’s parents, the May and Billy MacMillan Foundation partners with institutions that provide educational opportunities for financially disadvantaged students. MacMillian launched the charitable fund with his half of the Nobel’s monetary award, and he’s padded that sum by donating the honoraria from the many speeches he’s given since he became a Nobel laureate. Each year, the foundation will select a different educational institution and make a grant to support access for underprivileged students, starting with the University of Glasgow.

“If you don’t have money, you don’t have opportunities, so we decided to support some institutions that really push for people who don’t have the advantages that others might,” said MacMillan. “There are driven, smart, intelligent people everywhere, and it shouldn’t be about where you’re born. This notion is close to my heart and hopefully we can make a small impact and give all students the same opportunities for success.”

Now that’s what cool looks like.