Making audacious bets on character: Mitch Henderson ’98 went back to class to connect with his basketball players

When Mitch Henderson ’98 visited the Princeton campus in 1994 as a basketball recruit, he was already an incredibly accomplished athlete. He was nearing the end of a high school career that would earn him 12 varsity letters at Culver Military Academy in Indiana, where he was named all-state in three sports — football, basketball and baseball — and was a few months away from being drafted by the New York Yankees.

Over a bite at Conte’s Pizza, Pete Carril, the Tigers’ legendary coach, courted Henderson by telling him that his outside shot was “questionable” and that his left-handed dribble was weak. “This was so different than anything else that I heard from other coaches — I was sold,” Henderson said years later. “One of my strengths as a player was how hungry I was to improve.”

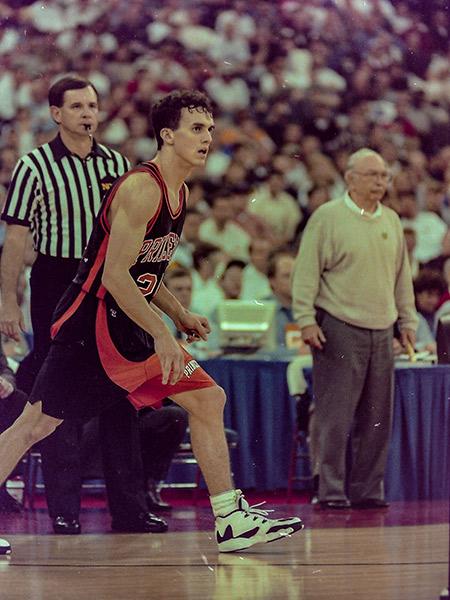

Henderson became a four-year starting guard at Princeton and helped lead the Tigers to three straight Ivy League titles and a historic NCAA Tournament upset of UCLA in 1996. In his final two seasons, playing for coach Bill Carmody following Carril’s retirement, the Tigers cracked the top 10 in the national rankings and won 28 straight Ivy League games while recording a 51-6 overall record. Henderson led those teams in steals and assists — at least a few of which, presumably, he dished with his left hand.

Today, as the Franklin C. Cappon-Edward C. Green ’40 Head Coach of Men’s Basketball, Henderson is working to build upon Princeton’s winning basketball tradition after last year’s squad became the first Tiger team to reach the Sweet Sixteen since 1967.

In his 13th season at Princeton, Henderson has his own way of coaching, but he hasn’t forgotten his mentor’s first recruiting lesson. “We try to be really direct with student-athletes during the process,” Henderson said, “and I always give the high school player a nugget of truth: ‘Do you mind if I tell you something that I think you can improve on?’ We watch the player’s response to that question very closely because that’s very much who we are. We expect that you would have a similar spirit of improvement.”

Anything is Possible

The NCAA basketball tournament is famously known as March Madness, and last year’s Princeton team sparked nationwide pandemonium after they shocked No. 2 seed Arizona. The No. 15 seed Tigers followed that stunner with a decisive win over No. 7 seed Missouri, leading guard Blake Peters ’25 to exult, “Anything is possible!” in a postgame interview that immediately went viral. Henderson and his players were media sensations for an entire week. Television, radio and national publications chronicled the students’ every move, from researching their senior theses to cramming for tests on the team bus to accepting well-wishes from politicians. Henderson was the coach of the moment, the self-assured guy who explained how a program that did not offer athletic scholarships could compete with the best teams in the country.

If Henderson seemed to have all the right answers for the cameras, his feet remained firmly on the ground. Not only did Henderson have firsthand experience of being a celebrated underdog who becomes the face of March Madness, but he also understood all the bends in the road that led to last season’s success.

When Henderson was named Princeton’s head basketball coach in 2011, the stars seemed to align. For 11 seasons, he had been a top assistant for Carmody at Northwestern, where he learned from one of the best basketball minds in the country and helped the Wildcats develop an up-tempo offense that raised the profile of the program in the competitive Big 10 conference. At Princeton, he inherited a team that was 25-7 the year before, had tied for the Ivy League championship and reached the NCAA tournament. But in the first game of his much-anticipated return to his alma mater, the Tigers were stunned by Wagner College, 73-57. The setback was followed by others, and before Henderson could get comfortable, his Tigers were 1-5.

“I’ll never forget that Wagner game,” Henderson said. “It was 12 years ago, but for me, it’s still very vivid. I can still see each play and where it went wrong. When you first get a head coaching job, you think you know everything, but there’s a lot you don’t know. The self-doubt creeps in right away. We had a talented team, and I don’t want to take all the blame, but I probably should. I was still learning.”

Not everyone was patient with Henderson. In the wake of the team’s sluggish start, emails began to arrive from longtime fans who asked — in less polite terms — “Why did Princeton hire this guy?”

Just when he needed it most, Henderson received a nudge of encouragement that made a huge difference. “I received a note from Luis Nicolao, who was then the head coach of Princeton’s men’s and women’s water polo teams, that said, ‘Hey, you’re doing great. Keep going,’” Henderson said. “I can’t tell you how much that note gave wind to my sails, knowing that one of my peers was watching out for me.”

Henderson and his players regrouped and rallied to win 20 games in his rookie season, the first of six 20-win seasons he’s recorded at Princeton. When he looks back at that year, there was no obvious turning point, no moment when things began to click. “The journey is never a straight line,” Henderson said. “It is always up and down, and I’ve been on the other side of it: the lows are really low. So when it comes together, like it did last season, it is a beautiful thing, like making music. It was awesome to watch, to the point where it was hard not to smile during games.”

Care Package

When Henderson was a Princeton player, he didn’t smile much. He was known as an intense competitor who played through injuries, including a broken nose, and never backed down from anyone. When Princeton faced undefeated North Carolina in a nationally televised game in 1997, the 6’2” Henderson got tangled up with and exchanged words with Antawn Jamison, Carolina’s 6’9” All-American. “I felt that I could go toe to toe with anybody,” Henderson said. “I probably shouldn’t have been going head to chin against Jamison, but I didn’t fear those moments.”

So it’s slightly surprising when Henderson says that the secret sauce to his recent teams might be lightheartedness and joy. That wasn’t always the case. Early in his coaching career, Henderson couldn’t help but show his players how he wanted things to be done on the court by doing them himself in practice. He could be exacting and critical, and not every player responded. Instead of opening up, some players closed down, he says now.

“If you [hastily] ask a player a question with some sort of intention in mind of getting the answer you want, you are going to receive an answer that you weren’t prepared for,” Henderson said. “It’s hard to describe this, but it’s a horrible experience when they tell you something truthful — because they’re almost always right. Actually, they’re always right. And the one thing worse than that is when they don’t tell you because they’re not communicating with you.”

If perfection is the aspiration for a sports team, Henderson discovered that failure became the common ground that helped him connect with his players. “These players arrive with the expectation that they should be this perfect Bill Bradley-like Rhodes Scholar who makes every shot, but it just doesn’t work that way,” Henderson said. “I’ve learned far more from losing than winning, and being more open with our players about my own self-judgment, which can be brutal, has allowed me to connect with them. Bringing failure into the process can take time, but we welcome it. I think it might be the most important thing that we talk through as a team and are working on together.”

To do so, Henderson works hard to support his players away from the court. That means meeting them not only as Princeton basketball players, but as Princeton students. What began as a self-improvement exercise became a happy accident: Henderson decided to sit-in on a class — HIS 383, “The United States, 1920-1974” — simply because he was fascinated by the subject. When he noticed one of his players in the class, it only seemed natural to walk and talk after the lecture ended.

“I found that walking to and from class is an incredible way to have a conversation — as opposed to some face-to-face sit down,” said Henderson, who made it a habit to sit in on his other players’ classes. “We never talk about basketball; we talk about the class and how things are going on campus. You worry about the ones who insist ‘I’m fine, I’m fine,’ because that’s how young men can be at that age. How do you get them to unfold their wings? You can’t force it; it needs to come out of them in a very natural way, and those encounters are a great way for them to feel comfortable. I stumbled onto this, but it’s my little secret.”

When Henderson and the player reconnect at practice after their class, they have an extra layer of understanding. It’s not just basketball. That positive, more open style of communication can be contagious.

“I think we’re a peer-led program, and there’s nothing stronger than one of your teammates saying, ‘Hey, I need you to do better here,’ or, ‘I’m really proud of you,’” Henderson said. “That’s more powerful, in my opinion, than anything I can do.”

“More so than ever, my role is to be crystal clear on the standards, hold them to account, and then just care, care, care,” he added. “I think that each team is a reflection of their coach and the culture the coach sets forth, and we have a caring group. Last year’s group of guys, in particular, was relentlessly supportive of each other, unlike anything I’ve ever seen. They bet on each other and discovered how much more fun it can be when you are rooting for somebody else to do great things. These are the things that are directly related to winning that no one categorizes.”

More Than Winning

There has always been an art to recruiting a player to Princeton, since the academic standards of the University demand a special quality of student-athlete, and Henderson leaves no stone unturned in his research to find tomorrow’s Tigers. Obviously, the superb court skills need to be there, and Henderson looks for talent that can thrive in an offense that is fun, dynamic and physical — “not necessarily your dad’s Princeton team,” in his words.

“I love backdoor layups, but we had no backdoors in the win against Arizona,” he added, referencing the signature staple of Carril’s famous Princeton Offense. “Princeton basketball has always been about, ‘What are you doing on each possession to make your teammates better?’ and that’s still what we’re doing. We’re just doing it a little differently. We’ve taken the things that I think of as Princeton basketball and recruited a caliber of player that plays absolutely without fear.”

In addition to the emphasis on self-improvement, Henderson focuses on the little things that don’t necessarily appear in the high school player’s box score. How did the player react when a teammate dribbled the ball off his own foot and made a turnover? How did he react when he made the same mistake? Did he hustle back on defense to take a charge that changed the momentum of the game?

“I care a lot more about how somebody reacts to a bad play for the team then the bad play itself,” Henderson said.

The scouting doesn’t stop after the game’s final buzzer. Henderson pays close attention to how a recruit greets young fans after a tough game. How does he treat his mom and dad during his official visit to Princeton? How does he behave when he thinks no one is watching?

“People would be surprised how much background work we do,” Henderson said. “When I visit a school, I try to talk to everybody to find out about a player — school janitors are really helpful. They know what a student is truly like. We want to know what we’re getting because once they’re at Princeton, they’re ours for four years.”

During those four years on campus, Henderson urges his student-athletes to absorb every drop of the Princeton experience. He wants them to give their all on the court, but the most valuable and long-lasting experiences should be the relationships they develop on campus and the contributions they make to the University community.

“Being great on and off the court is synonymous with what we are here at Princeton,” Henderson said. “Having character integrity in what you do matters in the way in which you play. Then the way in which you play is who you are, not just what you do. I believe that our team and the way we play together is reifying what the University stands for — ‘What are you doing on each possession to make your teammates better?’ is a version of ‘In the Nation’s Service’ — and we take that very seriously on the court and in the classroom.”

For Henderson, last year’s magical run in the NCAA Tournament validated all of the hard work, but he expects more. “The day I got back here [as coach], I saw no reason why we couldn’t be nationally relevant every year,” Henderson said. “There’s no doubt that the guys on this team feel like they 100% belong on the court with any team in the country.”

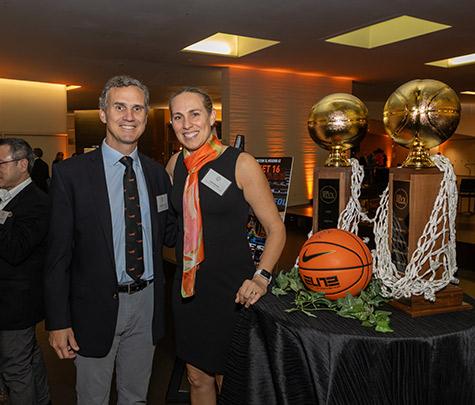

The wins and losses matter, but 25 years after he graduated and following more than 12 seasons as head coach, Henderson has a fuller definition of success and a richer appreciation for the relationship between coach and player. At the recent wedding of one of his former players, he marveled as the conversation shifted from glory-days Jadwin memories to the multiple ways that they were contributing to their communities, and how they could be doing more.

“We are all more than our record,” Henderson said. “I define success as a coach now as: Did they grow both as a player and as a person when they were at Princeton? Standing for something larger than winning — giving and caring and loving — means a lot to me. This is the charge I think of as more important.”